[slider_pro id=”169″]

FERGUS S KELLY

Derreen Books, 2015

pp 94 60 col ills h/b

€30.00 ISBN: 978-0-993306-30-3

Paula Murphy

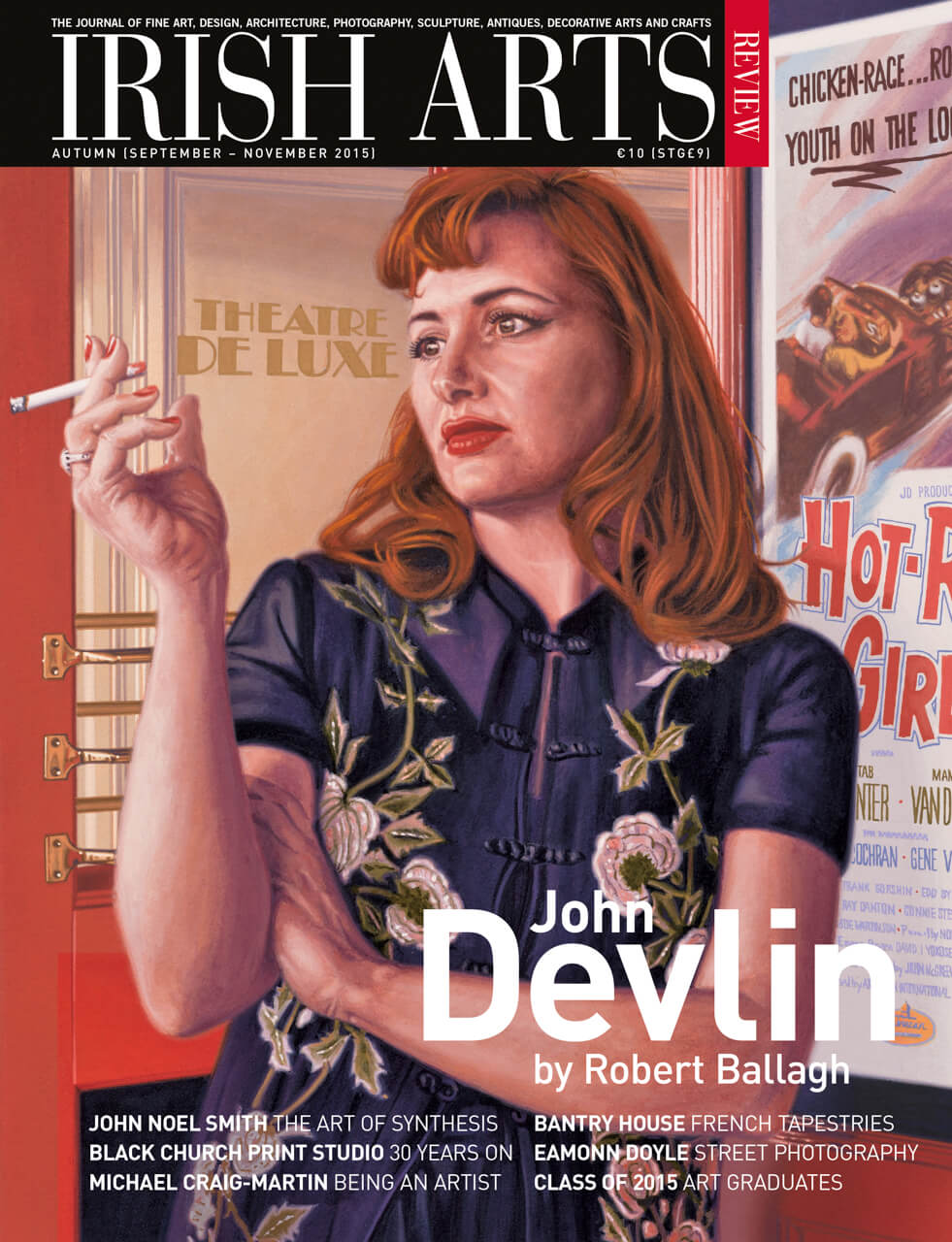

Fergus Kelly’s recent book on the life and work of his father, the sculptor Oisín Kelly (1915-81), was published to celebrate the centenary of the latter’s birth. The publisher, Derreen Books, is a Kelly family enterprise and this, its first publication, is tasteful, personal and informative. A particular highlight is the quality of the photography by Hugh McElveen. Oisín Kelly is best known for his public sculptures, notably the Children of Lir (1971) and the Larkin statue (unveiled 1979) in Dublin and the Two Working Men, at County Hall, Cork. While not ignoring the public work, Fergus Kelly has chosen in the illustrations to concentrate on a selection of the less familiar aspects of his father’s output – the small sculptures, some of which are models for the public work, and the design and craft work.

A professor in the School of Celtic Studies in Dublin’s Institute for Advanced Studies, Fergus Kelly makes no claim to art historical expertise and yet his earlier text on his father published in the Irish Arts Review in 1989 remained one of the main sources of information on the sculptor for many years. Here, in his new publication, in addition to a ‘life and work‚’ text, Kelly junior has chosen to include a selection of Kelly senior’s writings. That the sculptor was an art teacher in St Columba’s College, Dublin for almost twenty years and that he was associated for nearly two decades with the Kilkenny Design Workshops make his thoughts on art and art education of particular interest. He was vocal about his dislike of the differentiation between functional art and fine art work: ‘I used the word ‘artist‚’ but craftsman or technician would have served equally well‚’ (‘Workmanship‚’, foreword to a travelling exhibition, 1977).

The nature of art, and sculpture in particular, changed dramatically in the course of Kelly’s lifetime. Although he remained a traditional practitioner, he acknowledged that the fixedness of art had disappeared: ‘The how of art has always been contingent on the what of art and it is the what of art which, in my lifetime, has changed out of recognition‚’ (‘Rosc and the National College of Art‚’, The Irish Times, 28 December 1971). The Rosc exhibitions were instituted to educate the Irish public and Irish artists in contemporary developments in art. In Rosc ’71 the new ‘what of art‚’ could be seen in the work of artists such as César, Robert Morris, Claes Oldenburg and Jean Tinguely, work that had little connection with the sculpture of Oisín Kelly. Like Seán Keating, Kelly had comment to make about the art that was on display. However, unlike Keating, he took a positive stance, recognizing the importance for art students of seeing contemporary innovative work. Identifying that ‘aesthetic opinions, for most of us, are fixed for life at what is slightly avant-garde when we are eighteen or so‚’ and that what was on display was the aesthetic of the day for young would-be artists, Kelly had the wisdom – at a time when the art-teaching syllabus was being questioned – to recognize the meaninglessness of academic art education for such students.

Paula Murphy is editor of Sculptors and Sculpture 1600-2000, volume III, Royal Irish Academy and Yale University Press 2014.