The study of fragments is second nature to Jason Ellis, writes Paula Murphy of the sculptor’s collection from last year.

‘It is the fragment and the fragmentary state that are the enduring and normative conditions; conversely, it is the whole that is ephemeral, and the state of wholeness that is transitory’.1

The fragment has had a constant and often revelatory place in the history of sculpture as a result of its significant role in the learning and making process. However this presence was augmented when, eventually and inevitably, it became an end in itself. If always forming part of the practice of sculpture in its preparatory stages, its uniqueness as an independent work became manifest in two very different ways: firstly in its increasing manifestation as the remnants of a ruined sculpture – ruined by way of iconoclasm or merely by the passage of time – whereby it became an acceptable replacement for the original piece; and secondly, in the early modern period, as a bona fide finished work.

The at once complete and incomplete state of the fragment as sculpture allows for rich engagement with the work, permitting particularly creative participation on the part of the viewer. The fragment is simultaneously old and new, classical and modern, figurative and abstract, detail and whole.

Jason Ellis was destined to work with the fragment. If it has been the norm for sculptors to learn their profession in art school and in working with other sculptors, Ellis can be seen to have followed the traditional route in his early career. However, in reality he honed his learning experience in the sculpture conservation work he carried out for many years in Ireland and for which he was renowned. Conservation requires careful study of individual parts of a sculpture to come to terms with the practice and process of the original maker of the work. Thus the study of fragments is second nature to Ellis, who cites as inspirational the carving of new toes for a figure on a monument by John van Nost the younger in the crypt of Christ Church Cathedral in Dublin – not, in the end, the toes themselves, but his close observation of the sculpture led to the discovery of what he described as the effortless carving of one of the arms of the figure, which he was later to redeploy in Supplicant.

Making the decision, in 2006, to focus on the creation of his own sculptures rather than renewing the work of others was a turning point in his career. Now this exhibition marks a further development. His sculptures heretofore have been insistently abstract, concentrating on form, material and finish. By contrast, these new works – a range of dissected body parts on display in the Oliver Sears Gallery, Dublin – are inherently figurative. In their fragmented and independent state the forms achieve abstract status momentarily before being returned to the realm of the figurative in their naming – a long fluid form carved in Shelly black limestone becomes the Arm of Marat .

Ellis has created his segmented forms by way of life-casting. This now popular method was once derided, with Rodin in the 1870s spending considerable time and energy attempting to discredit the accusation that he had life-cast his model for that most famous of statues The Age of Bronze. However, the process bears no stigma today with Antony Gormley and Marc Quinn among the well-known practitioners. Ellis employs a unique route for these new sculptures, which often commence with the identification of an element of the human figure in an existing sculpture or painting before seeking it in the living human form to life-cast – a process of art into life into art.

In her book The Body in Pieces: The Fragment as a Metaphor of Modernity, Linda Nochlin identifies the French Revolution as a particular moment when artists began to interest themselves in the depiction of fragments – inspired by the guillotine and the chaotic violence that ensued during The Terror. Nochlin notes how in Géricault’s ‘matter-of-fact’ depictions of bodies ‘in pieces’ the coherence of the body is totally shattered, leaving the artist free to use the fragments at will.2 Ellis has identified Géricault’s truncated limbs as yet another source of inspiration for his work. Yet it is not the metaphorical or historical aspect of the 19th-century paintings that was inspirational – although the reality of a morbid presence must be acknowledged in Ellis’ sculptures – but the artistic freedom that permits independent selection.

While the works in this exhibition mark a significant development since Ellis’ show in the F E McWilliam Gallery in Banbridge in 2010 – Ellis’ Selene – has a loose connection with some of McWilliam’s leg work, his new interest in figuration was already hinted at in his display of plaster work in the Pearse Museum last year. Although plaster remains an important part of the process of making the work, Ellis is ultimately a stone-carver with a keen eye for the dynamic qualities of different stones. While his original concern with form, material and finish remains evident in his practice, a more thought-provoking dimension has been introduced in the new work on show in this current exhibition.

Jason Ellis ‘Corpus’ Oliver Sears Gallery, Dublin, 5 September – 25 October 2013.

Photography ©Ros Kavanagh

Paula Murphy is a senior lecturer in the School of Art History and Cultural Policy, University College Dublin.

1 William Tronzo, The Fragment: An Incomplete History, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, 2009, p. 4.

2 Linda Nochlin, The Body in Pieces: The Fragment as a Metaphor of Modernity, Thames and Hudson, London, 1994, p.16.

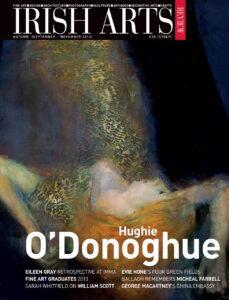

From the IAR Archive

First published in the Irish Arts Review Vol 30, No 3, 2013