Editor’s Letter

The Alfred Beit Foundation (ABF) was controlling Russborough House and Estate for twenty-six years before 2002, when it applied for, and was granted, the first in a total of €2 million conservation grants from the Heritage Council. That resort to public funds fundamentally altered the independent status of the Foundation, although its significance does not yet appear to have impressed the Trustees. When you accept handouts from the public purse it is axiomatic that you acknowledge the public interest. And yet the affairs of the Foundation continue to be conducted behind closed doors as if the public had no legitimate interest in the estate to whose very survival they have contributed so generously. The high-handed attitude of the Trustees was particularly apparent in the secretive manner in which they spirited the Rubens and other paintings out of the country for intended auction in London earlier this year; contriving to have the sale tied up before presenting the public with a fait accompli. Why they should have acted in such a furtive manner is hard to understand, but presumably their principal objective was to avoid any public discussion. Happily that strategem was frustrated following the huge public outcry against the sale.

Recently there was another demonstration of these incestuous tendencies from the Trustees in the re-appointment of Consuelo O’Connor to the board, after An Taisce had withdrawn her as its nominee. The vacancy had created an excellent opportunity to invite a public representative onto the board, most suitably someone from the Heritage Council itself. But the chair decided otherwise; presumably with the intention of strengthening her own position on the board which now includes new representatives from the Irish Georgian Society and from An Taisce.

It is only fair to acknowledge that the role of the individual Trustees in this case is not a happy one. Some are not even professionally qualified to the task in hand, yet they have to give their time and effort to a responsibility for which they receive no remuneration (at least the chairperson, Judith Woodworth, has stated that she is not remunerated). That said, any Trustee who is faced with the decision to dispose of treasures entrusted to his/her safekeeping cannot be a happy man or woman.

Putting aside the current controversy, it has become pretty obvious that after almost forty years of much troubled existence, the time has come for a complete restructure of the ABF. Ideally the initiative for this should come from the Foundation itself, but that seems unlikely, and, as more public funds are going to be involved one way or the other, it may have to come from the Minister. Meantime, however, should not the National Gallery, which owes so much to the tradition and to the families of Russborough House, take the initiative in exploring the best way forward for all parties concerned? This country is extremely fortunate in having several, long established, independent cultural institutions, such as the NGI, all founded by private citizens for the benefit of the community. But they should not rest on their laurels when they are needed to contribute to the future survival of Alfred Beit’s ‘centre for the arts’ already housed, thanks to him, in a Palladian mansion – a problem which is now larger than it is fair to expect the present Board to resolve on its own.

[slider_pro id=”127″]

From IAR Autumn Edition

John Mulcahy visits the last resting place of Alfred and Clementine Beit in Blessington, County Wicklow.

The grave in which Alfred Lane Beit is said to be ‘turning’ after the latest debacle over his ever-troubled collection of art, is situated in the walled graveyard behind the Church of St Mary’s in the centre of the village of Blessington, Co Wicklow. What a strange final resting place for this London-born second son of a family of Sephardic Jews of Portuguese descent who had converted to Lutheranism while living in Germany and had made their fortune in South Africa. And the mystery remains, why did the owner of one of the greatest art collections in Europe decide to turn his back on English society in 1952 and retreat to the wilds of Wicklow?

According to himself at that time, ‘If I had been told a month earlier that I was going to live in Ireland, with which I had absolutely no connection, and would move my family collection there, I would have told my informant that he needed his head attended to.’ Yet Beit never offered any explanation for his sudden and strange decision to purchase Russborough House and move to Ireland. It was certainly not that he needed a mansion in which to house the family treasures as they were already adequately displayed in his very large residence at Kensington Palace Gardens in central London. Nor was it, as in Chester Beatty’s case, for financial/tax reasons as the Beit fortune was already wrapped up in elaborate trusts. So one is left with the assumption that he came to Ireland primarily because he didn’t feel comfortable living in post-war England.

Alfred Beit was born in London on 19 January 1903 and brought up in the very pampered conditions of the British upper class moving through Eton and Oxford before taking a seat in the House of Commons and inheriting vast wealth on the death of his father Otto Beit in 1930. But his formative years had been marred by the one great tragedy in his life, namely the suicide in 1917 of his elder brother Theodore, an eigthteen-year-old cadet in York Cavalry Barracks. Included in the suicide note left by young Theodore was the sad crie de coeure that ‘I cannot stand all this‚Ķ.I will have to go through hell another night‚Ķthe other fellows of my age don’t seem to like me’. Whether the source of poor Theodore’s torment was anti-Semitism or just plain British bullying is not known. Perhaps a mixture of both. But the death of his only brother in such circumstances must have left a deep scar on Alfred’s consciousness and indeed on his attitude to British society in general.

In the decade before World War II, Alfred was a celebrated playboy in London and even got himself cited in divorce proceedings brought by the Earl of Kenmare before he settled down and married Clementine Mitford in the year the war broke out. Happily at age thirty-six he was not called up for active service but immediately after the war and the Labour landslide that swept him out of the Commons, Alfred and Clementine took off for South Africa where they remained for seven years. It was very soon after their return to London in 1952, that Alfred bought Russborough and came to live in Ireland.

One of the drawbacks of inheriting great wealth is that the beneficiary seldom enjoys the challenge of making his own way in life. Thus Alfred never knew the satisfaction of a successful professional career and although from birth he was surrounded by great art, he never experienced the excitement of acquiring an art collection for himself. Burdened with the strangely assorted collection of masterpieces that his family had landed on him, Alfred’s relationship to this collection was, in reality, reduced to that of a curator. Of course he enjoyed showing it off to his many distinguished guests, but in time these domesticated masterpieces must have become as much of a responsibility as a pleasure to him. I was among the, mostly international, press corps who arrived down to Russborough on Saturday 27 April 1974, the morning after the Rose Dugdale/IRA robbery. We stood at the bottom of the great granite steps looking up to the front door until Alfred emerged and read out a short statement. No fuss. No emotion. Very stiff upper lip stuff although he had suffered a bang on the head. A very cool performance from this most phlegmatic of men although I have no doubt that he dined out on the story for years to come. Contrast this relationship to a collection with that of the Earl of Dudley who had acquired only five of the six Murillo paintings of the Prodigal Son series (now in the Beit collection in the NGI) from the Marques of Salamanca in 1867. Dudley thereupon set out in pursuit of the missing painting until he tracked it down to the Vatican to where it had been gifted by Queen Isabella of Spain in 1856. But how does one extract such a treasure from the Vatican of all places? Well Dudley did so in exchange for Fra Angelica’s Virgin in Glory with Saints and Bonifazio’s Holy Family thrown in for good measure. Oh yes. And 2,000 gold Napoleons which of course any canny dealer would ensure to carry on his person. Here was the thrill of the chase for a determined collector with long nights in the eternal city arguing the toss with creepy cardinals until the deal was done – and the sack of gold changed hands (See Irish Arts Review Spring 2012), ‘Prodigal Son Restored’ by Muirne Lydon). Strangely, having chosen Ireland as his new home, Albert Beit never acquired any important Irish art. One such opportunity arose in 1983 when four large views of Lucan House, the Weir and Demesne, (which is directly connected to Russborough by the river Liffey), painted in the 1770s by Thomas Roberts came on the market from Mrs Marshall Wright. They might have adorned even a corridor in the West wing at Russborough if Alfred had been so inclined. But Alfred was not interested in Irish art and these fine 18th century landscapes found a home instead in the National Gallery.

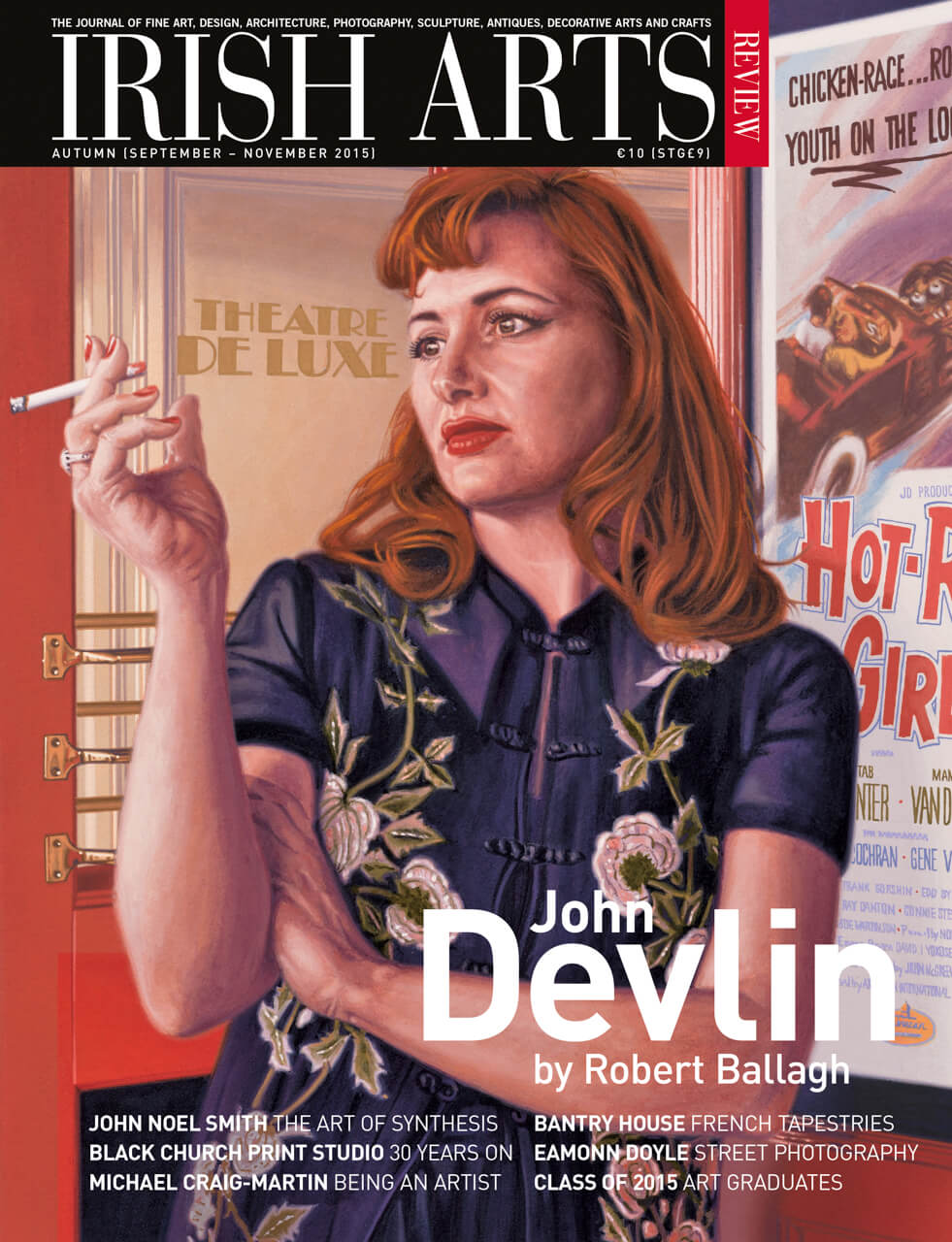

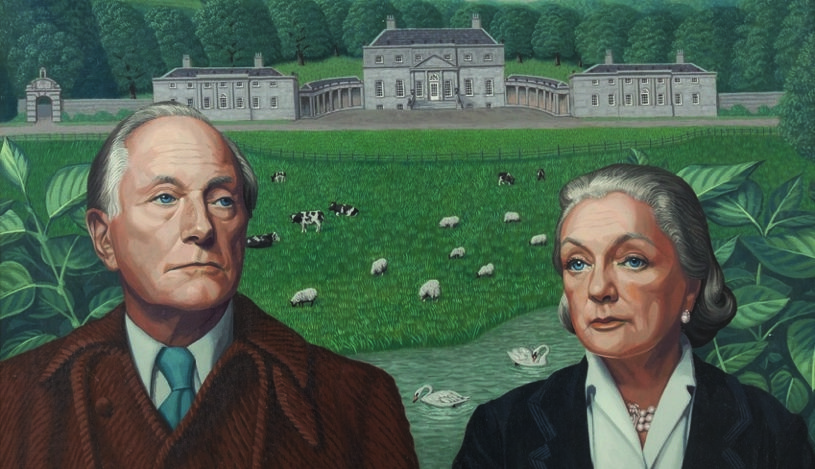

However Alfred did acquire a few paintings by Irish artists including one impressive picture by Basil Blackshaw called Greyhounds and, of course, he commissioned the classic portrait by Edward McGuire of himself and Clementine with Russborough House in the background. McGuire was a very meticulous but notoriously slow painter and he seriously annoyed the Squire of Russborough by dragging out this commission over a period of three years. Obviously the hauteur so accurately depicted on Alfred’s face in the portrait above failed to impress McGuire who also complained at the time that he was being underpaid for his hard work. At one point, it was even rumoured that he had slashed the canvass. Whatever, please examine the rose-like shoots growing incongruously on the left and right extremities of the picture shown here. The artist told this writer that he had inserted these rose stalks in honour of – Rose Dugdale.

The great disappointment in Beit’s life, of course, was that he and Clementine were childless – a circumstance which he blamed on the result of mumps contracted while at Eton. As a consequence, the question of securing the long-term future of the collection was always on his mind although it was nothing short of a miracle that it finally ended up in the safety of the National Gallery. The initial contact arose in 1965 when Clementine (not Alfred) wrote to the Gallery asking if they could lend some pictures to the Gallery while they were in South Africa for the winter. Needless to say, the then director of the Gallery, James White, was only too pleased to oblige and, surprise, surprise, the following year Alfred was invited to join the Board of Governors and Guardians. But it wasn’t until after the infamous robbery in 1974 that Alfred created the Beit Trust with a view to leaving the Russborough estate to the nation. And it was a full decade, and a second robbery later before he transferred the best 17 pictures to the Gallery, at which time he was already aged eighty-five.

Recently I paid my respects to Alfred and Clementine while visiting their last resting place in Blessington where the tombstone tells its own story. In the first place it couldn’t be simpler. A plain slab of stone lying horizontal and reading

In loving memory of Alfred Lane Beit

19th January 1903 – 12th May 1994

and of his wife Clementine Mabell Kitty

22nd October 1915-17th August 2005

They go from Strength to Strength

No titles, no symbols no embellishment of any kind; just the essential dates and the enigma left for those unfamiliar with Psalm 84.7 which concludes, of course, with the words ‘till each appears before God in Zion’.

In its position too, the tomb slab could not be more modest, positioned very close to, but not intruding upon, the adjacent railed off area devoted to those other long term residents of Russborough House – the Leeson family, later Earls of Milltown who built the House in the 1740s.

There was no evidence that Alfred had been turning in his grave. That would not be his form.

In references herewith, I am indebted to the magnificent volume by William Laffan and Kevin V Mulligan, Russborough, A Great Irish House, its Families and Collections with stunning photography by James Fennell.

John Mulcahy is Editor of the Irish Arts Review.