Robert Ballagh admires John Devlin’s painterly technique and laments the lack of interest from curators and critics who prize conceptual art over the handmade art object.

One aspect of the art game that has always intrigued me is how, at any particular period in history, some artists are elevated to great heights of fame whilst others of equal ability languish at the margins. One certainty is that the distribution of honours has always been due to factors more complex than the exercise of talent alone.

For example, when Vincent van Gogh died, none of his paintings had sold during his short life, yet, today, he is one of the most popular and sought-after artists in the world. What this remarkable outcome proves is that the passage of time will nearly always allow for an accurate evaluation of the true merit of an artist’s work to emerge.

This eventual acceptance, however, provides cold comfort for those artists no longer around to enjoy such posthumous acclamation. Without question, the causes as to why some artists are singled out for success are both convoluted and complicated. Certainly, being in tune with the dominant fashion or taste of any particular period must be recognized as a determining factor. For example, during the age of empire, there was plenty of work for painters of battle-scenes or portraits of emperors and generals. On the other hand there was scant recognition for artists who chose more modest or intimate themes. Today, as far as the individual artist is concerned little has changed, even though power has shifted from emperors to curators.

In the contemporary art scene, works of art are chosen and promoted in direct proportion to their effectiveness in supporting the concepts, themes or notions put forward by the legion of curators who dominate current art discourse. At present, the work of art can no longer speak for itself, it remains incomplete without the addition of relevant critical information. As Tom Wolfe, the American writer and critic confessed, ‘I had gotten it backwards all along. Not seeing is believing, you ninny, but believing is seeing!’

Notwithstanding such imposed strategies, many artists, whose work actually conforms to the capricious conceits of the standing army of curators, still find themselves passed over for promotion.

To be noticed in today’s competitive art world, artists need to possess not only a powerful personality, but also a relentless drive for self-promotion. Robert Hughes, an Australian writer and critic noted that the 20th century began with Cubism, to be followed by Dadaism, then Surrealism, Futurism, Abstract Expressionism and many other ‘isms’ but today, he concluded, there is only one ‘ism’ left- ‘careerism’!

In Ireland, and in other countries that share a similar historical experience, artists find they have to deal with an additional disadvantage. This is where local elites striving to reflect internationally sanctioned notions of importance continually fail to appreciate the response of local artists to local conditions and plump instead for those artists whose work conforms to internationally accepted standards. Brian O’Doherty, the artist and writer, memorably described such behaviour as ‘doppelg√§nger provincialism’.

In my experience there have been several talented Irish artists who have not received the recognition they deserve and that list includes the subject of this essay.

John Devlin was born in 1950 and raised in Booterstown, a quiet suburb in south county Dublin. Having the privilege of knowing his father and being acquainted with his larger than life personality, I’m of the opinion that the father must have played a significant role in the future development of the son. Johnny Devlin senior was not only a consummate musician, but also an individual with strong views on a wide range of topics which he was prepared to articulate with both wit and wisdom. As a musician, he not only fronted his own dance band, but also worked as a musical producer, director and arranger for the national broadcaster.

John junior was always passionate about music but when it came to a career choice he took a different path when he entered the National College of Art and Design in 1968. By 1970 he had become sufficiently proficient as a contemporary painter to have work chosen by both the Irish Exhibition of Living Art and the Independent Artists. In 1971 he won the Carroll Award in the Living Art exhibition and the following year the Alice Berger Hammerschlag Award; also, in 1972, the Davis Gallery in Dublin staged a successful two-person exhibition featuring Devlin, together with work by a friend from college, Martin Gale.

Yet, in spite of such early acclaim, John Devlin became acutely aware of the depressing reality that economic survival in Ireland through the sale of paintings alone was practically impossible, consequently, in 1972, he accepted a post in the Abbey Theatre as a graphic designer. After some time at the Abbey, realizing that he lacked certain proficiencies, he decided to sign up for work in an advertising agency where he successfully picked up a wide range of useful graphic skills. In 1973 several of John Devlin’s paintings were chosen for an exhibition ‘Aos óg – Art Irelandais Actuel’ at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, and in 1979 the Octagon Gallery in Belfast staged a solo exhibition of his work, yet, like most of his contemporaries, he still continued to experience the disheartening difficulties of earning a living from his work as a painter, so he persisted with his involvement in the advertising business. However, in 1985, he decided to switch direction and accepted a job in Emerald City, an animation studio that had commenced operations in D√∫n Laoghaire. In 1989 he moved to Murakami-Wolfe, another animation studio, and in 1994 he made the challenging decision to move to Phoenix, Arizona to work for 20th Century Fox.

Devlin frequently succumbs to the temptation of including visual puns and general good humour in his work as a painter.

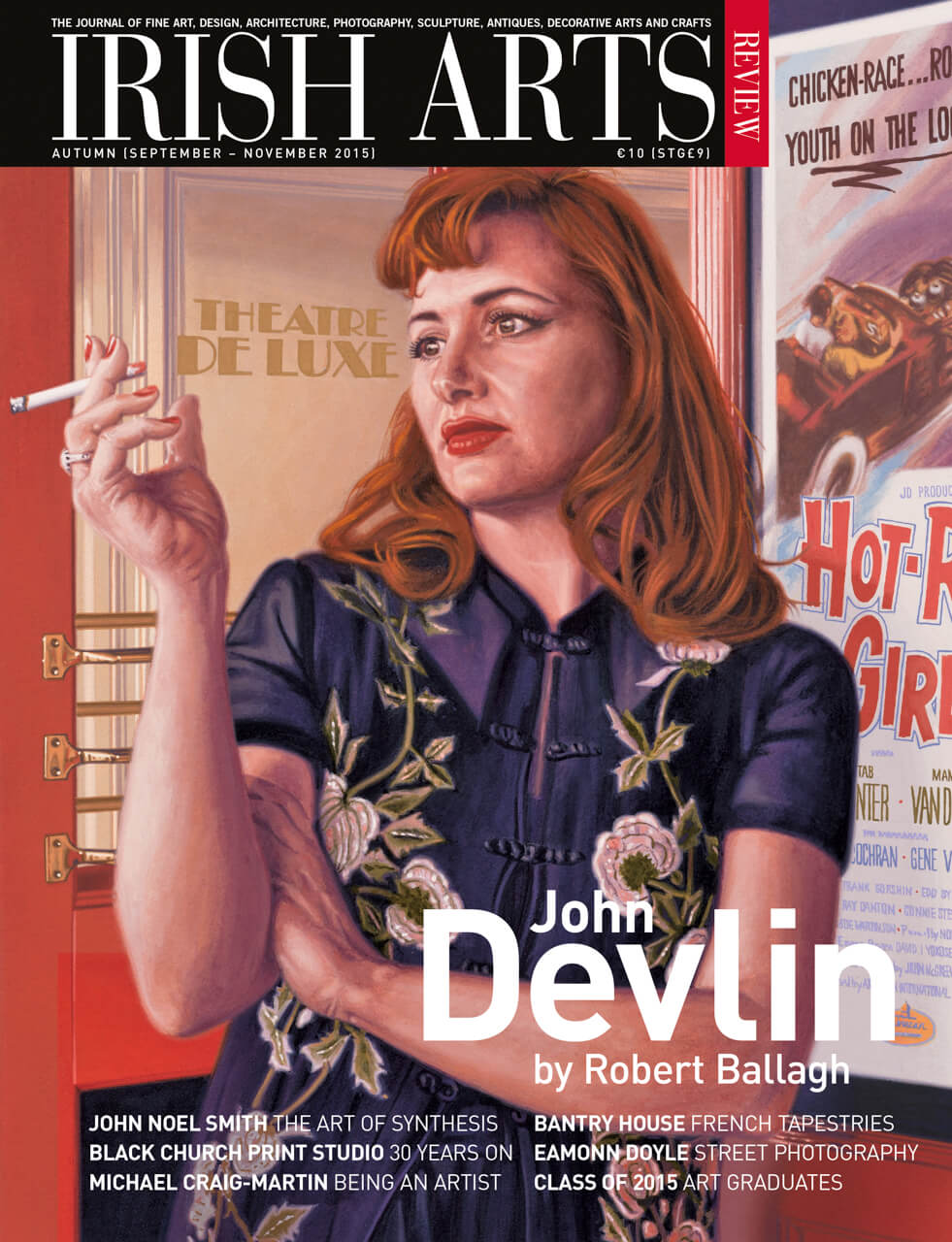

John Devlin’s responsibility in the animation world was to create the various backgrounds which appear behind the many cartoon characters drawn by animators. In classic cartoons like Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and Pinocchio the backgrounds were exquisitely rendered in watercolour but by the 1950s the chosen medium had changed to gouache. Through his work in animation John Devlin developed great skill in handling gouache, a tricky water-based opaque medium, and that skill is elegantly revealed in works like De Luxe (Fig 3).

When John Devlin first began exhibiting, his main influence, in simply formal terms, would have been international Pop art with its bright acrylic colours, razor sharp outlines and its cool, clean look, and certainly his own work executed in like manner was both successful and critically acclaimed, yet, on a personal level, he found the vocabulary of modern art rather limiting. He felt he wanted to say more than modernist technique would allow! To deal with that impediment he resolved to extend his competence as an artist, and to achieve this, he set about developing his drawing skills and switched to painting in oils rather than acrylic. One obvious consequence of this endeavor was the slow but steady emergence of a personal realism that was sufficiently accomplished for Wolfhound Press to reproduce one of Devlin’s paintings as the cover illustration for Contemporary Irish Art, published in 1982.

When Devlin returned to Ireland in 2000 he had become a sophisticated realist painter well able to incorporate intriguing personal considerations in his work but he was somewhat perplexed to discover that the art mandarins who originally supported him now exhibited meagre curiosity about the new work. For a start, there seemed to be little faith in the art of painting itself; museum directors, critics and curators had all but abandoned the handmade art object and instead had become obsessed with conceptual art, which usually comprised installations, video art and so forth. Also John Devlin, like his father before him and indeed like most of the Irish nation can not resist a comic yarn, so, quite naturally, he frequently succumbs to the temptation of including visual puns and general good humour in his work as a painter.

Unfortunately for him, art mandarins are a fairly joyless bunch and do not approve of such cultural ‘lapses’. They view art as a terribly serious business and certainly not as something that might possibly raise either a smile or a laugh.

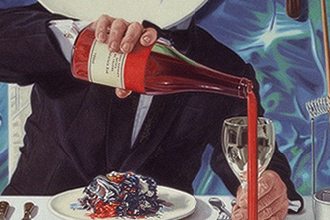

The painting El Rey del Mundo contains clear evidence of Devlin’s sense of humour (Fig 2). Towards the bottom right corner toy figures from Star Trek stand on an artist’s palette and a speech bubble held over Spock’s head contains a declaration in Spanish which translates as ‘This is art, Jim, but not as we know it.’ In many ways this ironic statement furnishes us with a useful key to appreciating certain aspects of Devlin’s work. For example, he constantly questions the nature of representation itself. How do artists go about representing three-dimensional objects on a two-dimensional plane? How does an artist represent a reflection and what is the nature of the reflected image? In El Rey del Mundo he paints small mirror screws around the edge of the work which imply that the painting itself is a painting of a reflection, a suggestion confirmed by the laterally reversed lettering on the canvas back, but, hold on, the speech bubble lettering is the correct way around, so we are compelled to ask – what the hell is going on? This is sophisticated stuff and is to be found in many of Devlin’s pictures. Isn’t it about time for the local curatoriate to open its eyes and recognize the significance of original Irish talent, like John Devlin, rather than continuing to clutter up our public spaces with work by international carpet baggers which is of scant relevance to either Ireland or the Irish people?

All images ©The Artist.

Robert Ballagh is an artist and a designer.