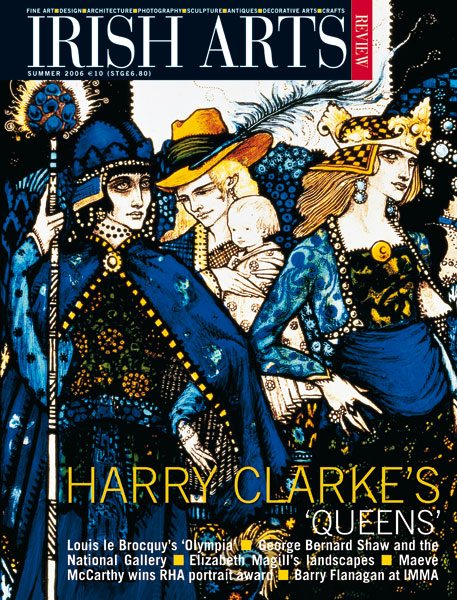

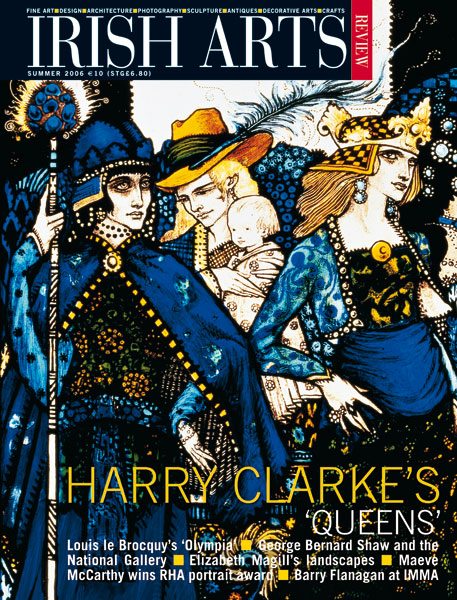

Nicola Gordon Bowe discusses Harry Clarke’s exquisitely detailed interpretation of Synge’s Queens, an ode to history’s most memorable female characters

Nearly ten years ago, a small leather travelling case was presented to Christie’s for inclusion in its 1997 annual Irish Sale in London 1 . Tailor-made, it contained nine small stained glass panels that had not been seen in public since 1928, when they left Ireland for good. Always in private hands, two of the panels had been reproduced once, in an English art periodical after they had been installed in ‘a library window at ‘Marino’, Ballybrack, the residence of the Rt. Hon. L.A. Waldron in Co. Dublin.2 But they had not been seen again until 1986, when the Dolmen Press dedicated an unpublished, limited edition monograph to them,3 and in 1989, when they were featured in the critical biography of their maker, Harry Clarke.4

In order to display them, Christie’s specially erected the two ornate black-painted wrought iron stands that Harry Clarke had designed and the cabinet-maker James Hicks had made when they had been loaned to the [Hugh Lane] Municipal Gallery in Dublin between 1925-7. Into these, the jewel-like miniature panels (30 x 18cm) were assembled, in sets of five and four respectively, beneath the clear glass labels that Clarke had inscribed with the lines of Synge’s poem that each illustrates. They were acquired by a private collector and, ever elusive, disappeared once more from the public eye.

They had originally been commissioned by Laurence Ambrose (‘Larky’) Waldron (1858-1923), eminent Dublin stockbroker from a landed County Tipperary family, Nationalist MP, Privy Councillor, Governor of the National Gallery of Ireland, Senator of the National University, bibliophile, collector and Old Belvederian. Clarke, also educated at Belvedere College, in the street next to his father’s ecclesiastical decorating business, had come to Waldron’s attention by 1912, probably through reports in the school magazine after the stained glass he made as a prize-winning art student had been awarded two coveted Gold Medals in London. At the same time, Clarke was beginning to make small black and white drawings for Dublin collectors in the manner of Aubrey Beardsley. Early in 1913, Waldron gave the twenty-six year-old student his first major commission, to produce a set of pen-and-ink illustrations to Alexander Pope’s ‘heroi-comical’ poetic parody, The Rape of the Lock, depicting six of the seven scenes which Beardsley had infamously ‘embroidered’ graphically only seventeen years earlier.5 Despite, or even because of, Clarke’s obvious allegiance to Beardsley, these wistful, fey interpretations led to a succession of graphic and stained glass works commissioned from Clarke by Waldron and his influential circle of friends.

These included armorial lanterns for Waldron’s picturesque Queen Anne Revival bow-fronted office opposite the Stock Exchange in Dublin’s Anglesea Street,6 and a variety of small decorative and narrative panels for his new residence, Marino, on the coast road overlooking Killiney Bay. Completed in 1907, Marino became the convivial meeting place for a well-educated circle of Dublin professionals, whose erudite members were wittily entertained over Epicurean feasts in its book-lined rooms, amidst exquisite Chippendale-revival furniture made by the contemporary Dublin cabinet-maker, James Hicks and Waldron family silver and paintings. The portly Waldron, ‘a connoisseur in talk, even more than in pictures, books or wine’,7 loved nothing more than to hurl quotations from his library of over 11,000 books to distinguished guests who might include Hugh Lane, Provost Mahaffy, and Oliver St John Gogarty.

Harry Clarke, well-read, shy but a witty conversationalist in congenial company, was fortunate to have been ‘adopted’ by Waldron, for it was here that he met most of his future patrons: Yeats’ biographer, Joseph Maunsell Hone, the prospective publisher of his next set of much more assured illustrations, to Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner8; the surgeon, Robert Woods, who bought them and subsequent black and white illustrations and stained glass panels; Bertram Windle, President of the (then) Royal University, Cork, whose cousin Edith Somerville would commission his first full-scale window for Castletownshend after his seminal Honan Chapel windows on the University’s grounds; the Chapel’s executor, Waldron’s neighbour, the lawyer John O’Connell, who would commission Clarke to make arguably his earliest and arguably his greatest masterpieces, eleven windows for the Chapel; William Starkie, Resident Commissioner of Education in Ireland and brother-in-law of the English illustrator Arthur Rackham, who was instrumental in arranging for Clarke to receive a travelling scholarship to study medieval stained glass in France. Women friends included the Sobranie-smoking Warden of Trinity Hall and Hone’s cousin, the miniaturist Jane French, both of whom would commission important stained glass panels from him. Waldron also introduced Clarke to another Belvederian, the barrister, art connoisseur and future National Gallery director, Thomas Bodkin, who would become Clarke’s most appreciative critic, advisor and friend. All would become key supporters of the Arts and Crafts Society of Ireland, along with Clarke, who became its most brilliant exponent, during the seminal 1914-1921 period of the Celtic Revival in the arts in Ireland.

Patronised by Waldron, who encouraged him to borrow freely from his extensive library, Clarke illustrated poems by Keats, W B Yeats and Oscar Wilde, Tales of Mystery and Imagination by Edgar Allan Poe and, notably, Hans Andersen’s Fairy Tales, in order to build up a portfolio. An introduction to George Harrap in London at the end of 1913 resulted in an enviable commission for a relatively unknown young artist, to produce not only forty full-page and other smaller black and white illustrations, but also sixteen in colour, for de luxe and trade editions of Hans Andersen’s ‘choicest’ tales. Clarke worked on these methodically, based in London until the outbreak of the first World War, in August 1914, building up his own unmistakeable idiom in dramatic, menacing, profusely patterned black and white and richly glowing colour. On his return to Dublin, before he headed off for the Aran Islands with his future wife, the painter Margaret Crilley, and their classmate Sean Keating (Fig 1), Clarke designed a bookplate for Waldron. This clearly illustrates their shared taste in books: legible among the spines depicted on the bookplate are the names Shelley, Keats, Pope and Synge.

As Waldron collected special editions by Irish contemporary writers, the Synge volume may refer to Elizabeth Yeats’ Cuala Press edition of John Millington Synge’s Poems and Translations. Published shortly after the thirty eight-year old writer’s tragically premature death, in March 1909, it included his poem Queens written c.1903 for the first time.9 In 1914, Clarke drew his first of several illustrations to Synge’s controversial play, The Playboy of the Western World (first performed in Dublin in 1907), which remained his favourite play and which, with Synge’s impassioned descriptions of his sojourns on The Aran Islands (published 1907) inspired Clarke’s first of six annual summer visits to Aran in 1909. He also made a note in his diary to illustrate Synge’s Queens.

The legendary heroines glide past on a theatrical stage strewn with impossibly decorative flowers, cushions, urns, birds of paradise and huge butterflies

While Clarke was working on his Hans Andersen, Ancient Mariner and other ephemeral graphic commissions, he began planning small coloured studies and then cartoons and stained glass for the full-scale windows John O’Connell invited him to make for the newly built Honan Chapel in Cork. The first nine nave windows were completed to justifiably rapturous acclaim just before his Hans Andersen illustrations were successfully published in London for Christmas 1916. Bodkin’s comment that here was a book illustrator who used an author’s work ‘merely as a starting point for a voyage of the artist’s fancy’ was to be as applicable to all Clarke’s idiosyncratic creations in whatever medium: ‘He has read the stories, been moved by them, and has gone away to evolve types, characters and patterns from his own profound and independent imagination’.10 His magnificently regal, iconographically intriguing depictions of Irish saints for Cork were considered technically and conceptually as splendid as their jewelled medieval forbears. It was while Clarke was completing the last two smaller windows for the Chapel’s chancel that he, or Waldron or Bodkin, had the idea of synthesising his first two major achievements in stained glass, and in pen and ink and watercolour, into a series of miniature panels illustrating Queens. He had already painted the small profiled head of a Madonna and Child, adapted from a 15th-century Donatello gilt terracotta relief, on to a five-inch roundel of thick flashed turquoise blue glass as his 1915 Christmas present for Waldron; this was before translating it into pale, red-haired St Gobnait for Cork the following summer. He had also included three little queenly figures processing in profile at the base of his St Ita window in April 1916. But it is the thirty or so tiny, exotically decadent-looking figures, mournfully bearing symbols of intercession and ranked around the elegant figure of Our Lady and completed by April 1917, that directly anticipate his Synge Queens, made between May and September of that year.

Each of the nine Queens’ panels closely follows the lines they illustrate which, like his Rape of the Lock and Ancient Mariner illustrations, are inscribed below, on a series of separate small lead-framed panels of clear glass. The figures depicted are recognisably Clarke’s, with their large, knowing eyes, tapering fingers, posturing stances and elaborate costumes (Figs 3 & 4), acting out Yeats’ prefatory description of Synge’s medievalist vision of the world, ‘where hatred played with the grotesque, and love became an ecstatic contemplation of noble life’. They were designed as a horizontal processional frieze, to be read at eye level from left to right, each panel inserted in the small bow-window panes of Waldron’s library at Marino. The first and last kelp-coated clear glass panels show the saffron-clad poet, balletically posed beside his coy love, no more resembling Synge than the fanciful Japonnist rock- garden around him evokes the Wicklow mountains (Fig 2). Languorously he unfurls a scroll, on which is written in tiny letters: ‘This and the following eight stained glass panels illustrating Queens by JM Synge were designed and executed by Harry Clarke for the Rt. Honourable Laurence A. Waldron… Sept. 1917…’ as he serenades his daisy-crowned queen by ‘naming queens in Glenmacnass’. In the final panel (Fig 10), he points at the exotic passing throng with ‘rare and royal names’, and concludes:

‘These are rotten, so you’re the Queen

Of all are living, or have been’

The legendary heroines glide past on a theatrical stage strewn with impossibly decorative flowers, cushions, urns, birds of paradise and huge butterflies. They are intricately painted on layered panels of flashed and yellow-stained glass, etched through to as many as six tones on ultramarine blue, sumptuous gold-pink, blue, rich ruby, blue, ruby and blue again. Each queen named in Synge’s twenty six-lined poem is fantastically depicted, whether exotically beautiful, pock-marked, villainous or alluring. Recognisable images of Leonardo’s Mona Lisa (Fig 6) , Titian’s Venus with a Mirror (Fig 7), Ambrogio Preda’s so-called Lucrezia Crivelli (Fig 7), Gustav Klimt’s Judith and Holofernes (Fig 8) and Gheerhaerts the Younger’s Lady in Fancy Dress (Fig 8) mingle among imagined temptresses. As Bodkin commented, Clarke’s happy ability to ‘combine imagination and erudition’ was compelling to Waldron and his circle of connoisseurs.11

Clarke intended to make another ‘Queen’ panel for Bodkin, who had advised him on Waldron’s set but, instead, chose Walter de la Mare’s melancholy poem, The Song of the Mad Prince, which he painted exquisitely on blue glass plated on ruby to give an unimaginable range of subtle shades. Completed in October 1917, it was mounted in a special walnut cabinet by James Hicks. The same month, Clarke drew Bodkin a pen and ink illustration of the first scene of Synge’s Playboy of the Western World, featuring himself, Keating and motley characters from Waldron’s ‘Queens‘.

Such virtuoso miniature cabinet panels were unique as book illustrations on glass. They were also extremely hazardous to complete successfully. Although Clarke continued to incorporate small narrative scenes on flashed and plated glass into his windows, he made few other autonomous panels over the next seven years. Those he did included magical illustrations of a Heinrich Heine poem, a Gustave Flaubert story, the Perrault tale of Bluebeard, Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Keats’ romantic Eve of St Agnes, and fourteen jewelled scenes depicting contemporary Irish literature, painted and inscribed on eight panels of poignant intricacy, shortly before tuberculosis overcame him at the premature age of forty-one.12

1. The Irish Sale, Christie’s, St James’s, London, 21st May 1979, lot 65. The panels were reproduced individually in a special pull-out illustrated section and as mounted. They far exceeded their estimated £150,000- £250,000, selling for £331,500 sterling.>‚Ü©

2 Thomas Bodkin, ‘The Art of Mr Harry Clarke’, The Studio, vol.78, no.320, November 1919, p.47, where the sixth and seventh panels were reproduced (in colour).‚Ü©

3 J.M. Synge, Queens, with nine colour reproductions of stained glass by Harry Clarke, designed by Liam Miller, photographed by Mark Fiennes, annotated by Nicola Gordon Bowe (Mountrath, May 1986).‚Ü©

4 Nicola Gordon Bowe, The Life and Work of Harry Clarke (Irish Academic Press, Dublin 1989/1995/2004); panel three was on the cover of Paul Brennan and Michael O’Dea (eds.), Entrelacs franco-irlandais: langue, memoire, imaginaire (Caen 2004).‚Ü©

5 These illustrations were sold by Waldron’s niece to the National Gallery of Ireland in 1936.‚Ü©

6 The extensive Harry Clarke archive, acquired by the National Library of Ireland’s Department of Prints and Drawings from a private collection in 2003, includes an annotated design for one such four-sided lantern, embellished with the outsize butterflies featured in both Clarke’s Hans Andersen illustrations and the ‘Queens’ panels.‚Ü©

7 Obituary, Irish Times, January 13th 1924. The Mycenean Waldron was lampooned by fellow Belvederian James Joyce.‚Ü©

8 Tragically, all the blocks for the illustrations, cover, and title page Clarke had drawn for this project were destroyed when Maunsel & Co.’s Middle Abbey Street premises were destroyed in the 1916 Easter Rising. Consequently, the book was abandoned. In 1917, Clarke needed the permission of Maunsel & Co. to use the words of Synge’s poem, Queens (see letter from Clarke to Bodkin, December 14th 1917, Clarke mss., NLI).‚Ü©

9 The Cuala Press also produced Synge’s Deirdre of the Sorrows in 1910 and W.B. Yeats’ Synge and the Ireland of his Time in 1911.‚Ü©

10 Thomas Bodkin, Studies, Vol.6, no.2, June 1917, p.299.‚Ü©

11 Bodkin, 1919, op.cit., p.50.‚Ü©

12 Clarke’s final masterpiece, completed in 1930 shortly before his death, was intended as Ireland’s gift to the League of Nations in Geneva; sold back to his family as unrepresentative of the new Free State, it was acquired by the Wolfsonian Foundation in Miami in 1988.

Image Captions:

1 Sean Keating 1889-1977 Thinking out Gobnait (Portrait of Harry Clarke) 1917 oil on canvas 76 x 76cm

2 Glenmacnass: a rocky glen and dramatic waterfall in the Wicklow mountains not far from the Synge family home at Glanmore Castle

3 Etain Echraide, the beautiful daughter of Ailill, King of Ulster, was married to Midhir, a king of the mythical Tuatha de Danann, in her first incarnation; then magically metamorphosed into a purple fly (here a butterfly), and reborn into a family of the Sidhe, when she married Eochaid Airem, High King of Tara.

Helen, the lovely daughter of the mythical Greek goddess Nemesis and Zeus, married Menelaus, King of Sparta, but loved Paris, Prince of Troy (she holds a tiny model of the city in her hand). Queen Maeve, rapacious daughter of a High King of Ireland, ruled Connacht until she launched into battle with Ulster, as described in The Táin.

Fand, a beautiful queen of the Sidhe, wedded to Manannán, god and ruler of the seas, was tragically in love with the mortal Cuchulainn, and thus known as ‘the tear that runs from the eye’. Deirdre, beautiful daughter of the bard Feidlimid, eloped with the warrior Naoise, although betrothed to the Ulster king Conchobar Mac Nessa, resulting in the lovers’ deaths and the downfall of the Red Branch of Ulster.

4 & 5 King Charlemagne’s mother, Villon’s ‘Berte au grant pié’ from his Ballade des dames du temps jadis poses beside Ronsard’s ‘belle Cassandre’ from his erotic ode ‘Ah! Je voudrais, richement jaunissant’.

6 The ‘Monna Lisa’ is a creditable copy of Leonardo da Vinci’s much reproduced painting

7 Lucrezia Crivelli refers to Ambrogio de’ Predis’ Profile Portrait of a Lady in the National Gallery, London. The Titian figure is derived from his Venus with a Mirror , now in the Mellon Collection, National Gallery, Washington DC. ‘Jane of Jewry’ Lady Jane Grey, Queen of England for nine days before being tragically executed aged sixteen, was born and raised on her parents’ estate, Bradgate, outside the city of Leicester, famous for its ancient Roman Jewry wall. She is depicted walking to the scaffold with the torch of her Protestant faith.

8 & 9 Judith bearing her bloodied sword in one hand and the hair of the newly decapitated head of Holofernes in the other is derived from Klimt’s painting, Judith II (as is ‘Jane of Jewry’ in the previous panel). The picture now hangs in the Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Venice.

9 Gloriana’s costume is copied from the portrait of Queen Elizabeth I as A Lady in Fancy Dress by Marcus Gheerhaerts the Younger in the British Royal Collection at Hampton Court.