Roger Stalley examines the relationship between the carvings of the mason and the metalworker in building and shrine decoration in 12th-century Ireland

The portal that adorns the cathedral at Clonfert must count as the most extravagant and flamboyant doorway in Ireland (Fig 2). The whole composition forms an eccentric and unexpected delight, a Baroque episode in the history of Irish Romanesque art. Flanked by an array of sculptured columns and arches, the door is surmounted by an acutely pointed gable, the latter enlivened by a series of mysterious human heads. When completed in the second half of the 12th century, it must have been a stunning sight, the freshly carved stone enhanced by paint, the carvings glowing with colour in the afternoon sun.

The portal was by far the most ornate feature of the ancient building, but it remains unclear whether it was part of a new church or an addition to an existing structure. The walls are now rendered, making it difficult to establish its architectural history. The portal itself was made of sandstone, the preferred material for most Romanesque carving in Ireland, and considerable efforts were made to acquire it. Geological analysis indicates that it was brought from a quarry at Killaloe, some 45 miles away. All but the last half mile could have been made by water, the boats laden with stone making their way through Lough Derg and up the Shannon. The decision to use Killaloe stone was presumably made by the master mason, who was charged with both the overall design and the construction itself. Along with fellow masons, his major task was to cut and shape the individual blocks, many of them embellished with intricate ornament. In total, approximately 400 individual pieces of stone were required for the portal, the carving of which was equivalent to three or four years’ labour for one individual. If several masons were employed, as seems likely, the carving might have been completed within a year or so. It is possible that a certain amount of carving was undertaken at the quarry, but on balance it seems more likely that most of the work was done onsite at Clonfert. While the new portal had many unique elements, it incorporated one feature from the past. The various responds and columns supporting the Romanesque arches lean inwards, an arrangement found in the lintelled doorways of Ireland’s most ancient churches. This was surely deliberate – homage, it seems, to history and tradition. Once the doorway had been fully assembled, the stonework could be painted, with the fine detail picked out in colour, a relatively costly and time-consuming operation.

To read this article in full, subscribe or buy this edition of the Irish Arts Review

Angela Griffith appraises Paul MacCormaic’s painting of Lucky Khambule, this year’s winner of the Ireland–U.S. Council and Irish Arts Review Portraiture Award

Rachel Thomas interviews Richard Malone, an artist who works across the media of sculpture, fashion and performance, pushing the boundaries of traditional sculpture.

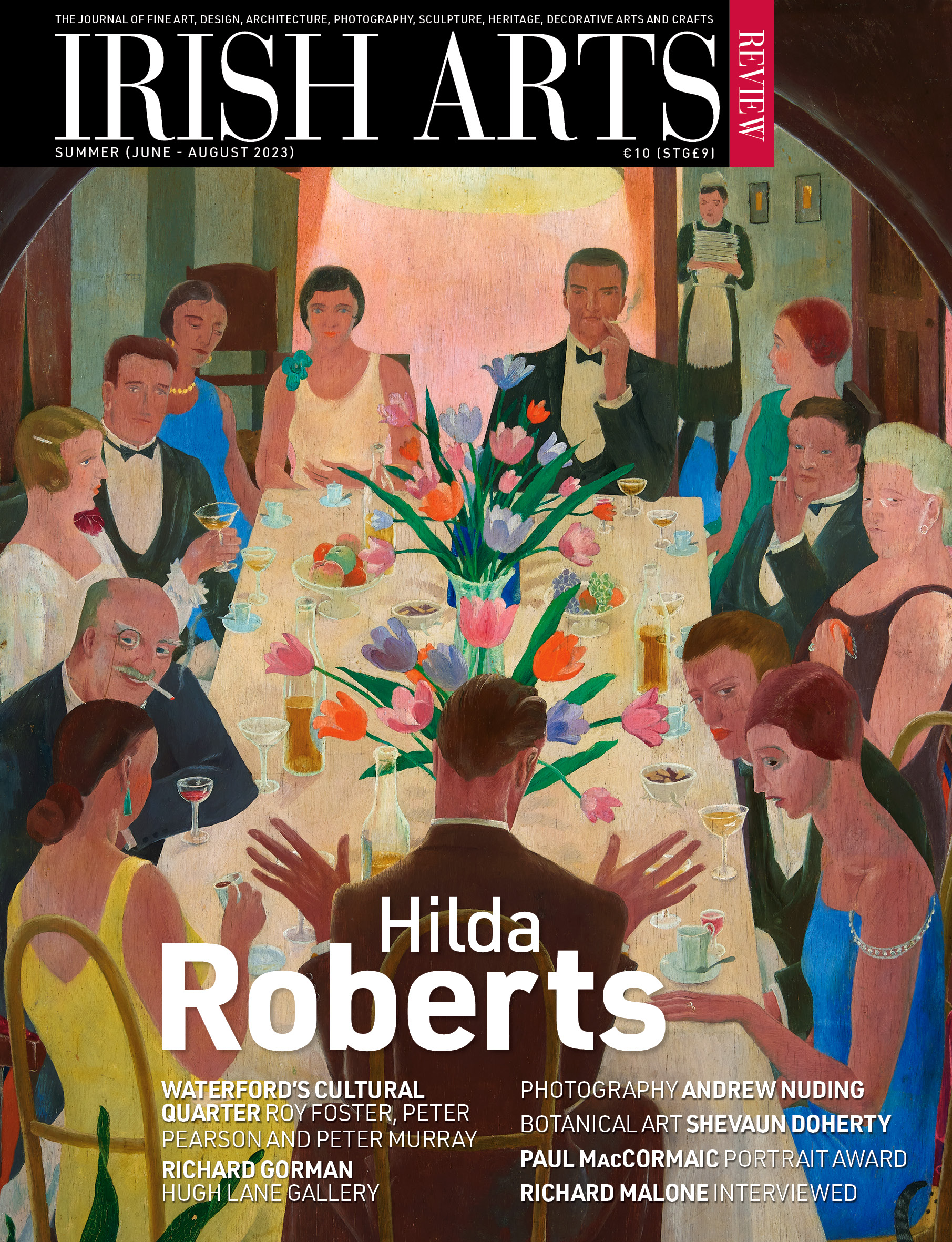

Hilary Pyle recalls the artist Hilda Roberts, two-time winner of the RDS Taylor Art Award, whose talents were apparent from an early age