Peter Murray examines the shifts in fortune surrounding the magnificent suite of paintings by the Guardi brothers brought to Ireland by the Earl of Bantry

Of all the treasures amassed by Richard White, 2nd Earl of Berehaven, the series of eight paintings illustrating Torquato Tasso’s poem La Gerusalemme Liberata, were undoubtedly the most precious. The work of Giovanni Antonio Guardi (1698-1760) and his younger brother Francesco (1712-1793), these paintings were displayed in the family’s magnificent house overlooking Bantry Bay for a century and a half. Today they are scattered across the globe, in museums in the United States, Canada, Britain, Denmark and Italy. A magnificent series of eight large canvases, the Guardis were brought to Cork in the 1820s, and, framed with elaborate gilt leather decorative borders, were mounted on the ceiling of a large drawing room at Bantry House. In her Rambles in the South of Ireland During the Year 1838, Henrietta Chatterton records her visit to the house, describing the interior as ‘quite a curiosity’: ‘The walls, stair-case, and bedrooms, are all covered with tapestry – even the ceilings of the staircases and passages. Some of it is very good, especially that in the drawing-room, which once adorned the palace of the Tuileries. The rooms abound with objects of virt√∫, and the ceilings of some are covered with paintings which formed the plafond of a palace at Venice. Most of the doors are covered with that stamped and gilt leather which was formerly so extensively used to decorate the palaces of Spain.’

The eight paintings by the Guardi brothers had been purchased as a set by Richard White, Viscount Berehaven, later 2nd Earl of Bantry (1800-1868), and his wife Mary during their Grand Tours of Europe in the mid 1820s, tours that took in Russia, Scandinavia, Spain, France and Italy. The Guardis may have come not from the city of Venice itself, but from one of the great houses on the river Brenta, such as Villa Pisani or Villa Contarini.

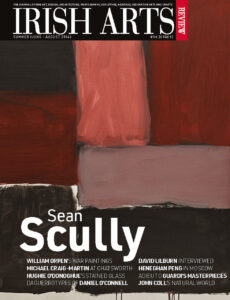

While the eight paintings acquired by the Earl of Bantry are agreed to be the result of a collaborative effort between the two Guardi brothers, Giovanni Antonio and Francesco, it is the former who took the lead in the commission, Francesco being better-known for his smaller vedute, depicting the buildings and canals of Venice, and for his conversation pieces. Giovanni Antonio worked on a far grander scale, and clearly at some speed, producing many paintings during his lifetime. Born in Vienna in 1698, his earliest known work, dating from around 1717, is Saint John Nepomuk in the Cogo Collection in Treviso, near Venice. An elusive artist, and not recorded as a member of the Venetian guilds, between 1730 and 1745 Giovanni Antonio was employed, primarily as a copyist, firstly by Count Giovannelli and later by Marshal Johannes Matthias von der Schulenberg (1661-1747). His Scene in the Garden of a Serraglio, painted around 1743 and now in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection, is one of a series of forty-three canvases depicting ‘Quadri Turchi’, or Turkish court life in Constantinople, produced for Schulenberg. His best-known work is a series of seven canvases, completed in 1750 for the organ loft of the church of San Raffaele Arcangelo in Venice. Other series by him are the ‘Roman Histories’ in the Bogstad Villa in Oslo and ‘Episodes from the Life of Joseph’, in the Lutomirsky Collection in Milan.

However, it is with the set brought by Richard White to Bantry, that the skill of Giovanni Antonio and his brother Francesco can be seen at its best. Based on engravings published in an edition of Tasso’s La Gerusalemme Liberata, these canvases are far from the heavy and ponderous compositions often associated with history painting. Light, sophisticated and elegant, they glow with a gentle Venetian colouring akin to the work of Titian or Tiepolo. First published in 1581, Tasso’s epic poem recounts the tale of the First Crusade, in which Frankish knights, led by Godfrey of Bouillon, capture the city of Jerusalem. The story inspired countless paintings and engravings, by artists such as Guercino, Poussin, Tiepolo and Delacroix. Published in 1745, the Albrizzi edition of Tasso, with twenty-one plates by Giambattista Piazzetta, achieved renown as a work of art in its own right. Although the Guardis based their compositions on those of Piazzetta, their interpretation was free and inventive. In Charles and Ubaldo Resisting the Enchantments of Armida’s Nymphs, for example, a vertical composition by Piazzetta has been considerably altered and elongated horizontally (Figs 7&8). The main figures, their clothing and attitudes, have not changed much, but the setting is more open and panoramic, and the treatment spontaneous and impressionistic.

At that time, none of the Shelswell-White family realized the value of the eight paintings, obscured by darkened varnish

The scenes from Tasso’s poem depicted in the canvases are: Charles and Ubaldo Resisting the Enchantments of Armida’s Nymphs; Erminia and the Shepherds (Figs 7&9); Single Combat between Tancred in the Presence of Clorinda,now in the Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen; Erminia discovers Argante Dead and Tancred Wounded (Fig 1) now in the Galleria dell’Academia, Venice; Sophronia Offers her Life to the Saracen King Aladine in Order to save the Christians, now in the Ferens Art Gallery, Hull; Tancred Baptizes the Dying Clorinda, (Fig 3) now in the Musee des Beaux Arts, Montreal; Godfrey of Boulogne summons his Chiefs to Council (Fig 6) now in the Norton Simon Museum in California; and lastly, Rinaldo and the Nymphs (private collection).

In the mid 1950s, Patrick O’Connor, curator of the Hugh Lane Municipal Gallery in Dublin, began to take an interest in the tapestries and paintings at Bantry House. Son of the Irish-American sculptor Andrew O’Connor (1874-1941), Patrick was a former soldier who had served with the 69th Regiment of New York during the Second World War. In 1955, he was planning an exhibition of paintings from Irish country houses, to take place at the Hugh Lane Gallery two years later. He visited Bantry House and befriended Clodagh Shelswell White, offering to help her find an American museum willing to buy some of the Gobelins tapestries. In addition to his curatorial work, O’Connor also dabbled in art dealing. He proceeded to purchase items from Bantry House, mainly books and drawings sold by Clodagh to meet her day-to-day living expenses. At that time, none of the Shelswell-White family realized the value of the eight paintings, obscured by darkened varnish, mounted on the high ceiling of the drawing room. Described as ‘eighteenth-century Italian school’, they were valued at five hundred pounds.

In August 1955, O’Connor offered to buy the eight paintings, for three hundred pounds. He pointed out that the canvases, with their elaborate but now dingy frames, made the drawing room too dark, and offered to repair and repaint the ceiling white. Clodagh agreed to sell, but negotiated a higher price. Eventually, on 15 October, O’Connor purchased the paintings for £1,200. They were taken down, the ornate decorative borders removed, but the sale was problematic from the outset, as Clodagh Shelswell-White was not legally at liberty to freely dispose of the paintings. When she and Geoffrey Shelswell married in 1926, Bantry House and demense were entailed to her first-born son Egerton (1933-2012), who on achieving his majority had become the sole owner of house and estate. Clodagh had fiduciary responsibilities. She was entitled to sell assets, but only with the approval of the Trustees, a body represented by the Bank of Ireland, and only if market value was obtained. She was entitled to live off only the interest of the asset sold, not the capital.

In the event, it transpired that Patrick O’Connor was part of a consortium of Dublin-based art and antique dealers, a consortium that included Neville Orgel, who had a gallery on Nassau Street, and two others. Not long afterwards, the art historian and dealer David Carritt, who had a reputation for discovering lost masterpieces, identified the paintings as being by the Guardi family. Thereafter things began to move swiftly. On behalf of a Geoffrey Merton, Carritt purchased five of the Bantry paintings. These were sent to London for restoration by Johannes Hell, a specialist who had trained in Berlin. Restoration took two painstaking years but what was revealed were paintings of very high quality (Fig 4). In the late 1950s, scholarly articles began to appear on the re-discovered masterpieces, including an article by W R Jeudwine entitled ‘A Guardi Rediscovery’ [Apollo 70 (1959): 173-175]. In January 1960 Merton loaned the five restored paintings to the exhibition Italian Art and Britain at the Royal Academy in London. These five were Charles and Ubaldo Resisting the Enchantments of Armida’s Nymphs, Erminia and the Shepherds, Single Combat between Tancred in the Presence of Clorinda, Erminia discovers Argante Dead and Tancred Wounded, and Sophronia Offers her Life to the Saracen King Aladine in Order to release the Christian Prisoners.

When seen at the Royal Academy, the paintings created a sensation, making headlines in Irish and British newspapers. Negotiations for their sale to international museums began, and four years later two of the most important were sold to the National Gallery in Washington. Another went to Copenhagen, one went to the Accademia in Venice (the sale being completed in 1984), while the fifth, Sophronia offers her Life to the Saracen King Aladine, was sold in 1967 to the Ferens Art Museum in Hull. The sale of these five works was handled by Agnews of London. The estimated value of the collection at this time was £500,000. The three paintings not purchased by Merton remained in Dublin, in the possession of Neville Orgel, who on 27 November 1963 offered them of sale at Sotheby’s in London, where they were purchased by a mystery dealer identified only as ‘Graham’. One of the three, Tancred Baptizes the Dying Clorinda, was gifted in March 1987, to the Musee des Beaux Arts in Montreal, by Michael Hornstein, a London dealer. Another, Godfrey of Boulogne summons his Chiefs to Council, was sold, through Schaeffer Galleries in New York, to the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena. The third, Rinaldo and the Nymphs, is thought to have been in the Stern collection in London in 1988, and is now in a private collection.

The breaking-up of the series, and the scattering of the eight paintings to different museums across the globe, represented both a loss to the art world, and to Ireland’s cultural heritage

When, in the late 1950s, the true value of the eight paintings became apparent, Egerton Shelswell-White, who had come of age and inherited Bantry house and its contents, but who was living in London at that time, decided to take legal action. A protracted court case ensued, in which Egerton effectively had to sue his mother Clodagh. The case also involved the Trustees (represented by the Bank of Ireland) and the three original Dublin-based buyers of the paintings. On 5 November 1959, the Irish Times reported O’Connor’s vain attempts to deny any involvement in the purchase. Distressed at the resulting publicity, Patrick O’Connor resigned as curator of the Hugh Lane, left Dublin and moved to New York with his family. On 20 December 1960, reports in the Daily Express and The Times precipitated the matter again into the front pages of the press. Geoffrey Merton, anxious to obtain a clear title to the five paintings he had purchased, agreed to pay Egerton £5000, in full settlement, so that he, Merton, would then be at liberty to sell them on to museums. A similar settlement was being entered into by O’Connor and his co-defendents, in which they agreed to compensate Egerton for the three paintings they still retained. However, in 1963 O’Connor died in New York, and this settlement does not appear to have been carried through.

The breaking-up of the series, and the scattering of the eight paintings to different museums across the globe, represented both a loss to the art world, and to Ireland’s cultural heritage. The paintings in Washington are highly-regarded and as recently as December 2013 were the focus of an evening organized by Laura Benedetti of Georgetown University and Peter Lukehart of CASVA, who presented music and readings relating to Tasso’s poem Jerusalemme Liberata, and the works of art it inspired. However, the association of the paintings with Bantry House has been consistently overlooked. Most accounts state that Carritt discovered the paintings in a shed in Ireland. The role of the 2nd Earl in acquiring these fine paintings as a set has been almost forgotten, and Bantry House is rarely mentioned as having been their home for over a century. Despite the loss of the Guardis and of many other treasures, Bantry House itself has survived, and has remained open to the public for the past fifty years or so. With its celebrated gardens and fine prospect over Bantry Bay (see Irish Arts Review Summer 2010), thanks to Egerton and Brigitte Shelswell-White, the house remains in good order, and is home to a wide range of cultural events, including the Bantry Chamber Music Festival.

Peter Murray is Director of the Crawford Art Gallery Cork.

Further reading:

Knox, George. ‘The Tasso Cycles of Giambattista Tiepolo and Gianantonio Guardi.’ Museum Studies 9 (1978): 89-95, fig. 28-29.

M ≠artineau, Jane, and Andrew Robison, eds. The Glory of Venice: Art in the Eighteenth Century. New Haven, 1994: 452, cat. 191, color pl.

For information on the Bantry Estate Collection see the library archives at UCC.