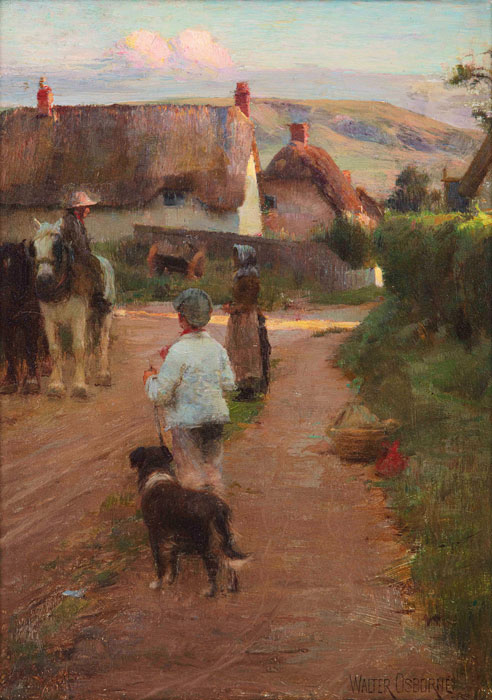

A Basil Blackshaw painting of a fighting cock catches the eye at De Veres. Unlike artists who move to the country and romanticise their rural locales, Blackshaw was a country man to the core. His horses, dogs and fighting cocks are not mere objects selected for our visual delectation – they were the creatures of his daily round. His landscapes are inspired by Dromara and the area near his original home in Co Down and by south Antrim, where he eventually settled and enjoyed hunting and point-to-points. He was better known to many of his neighbours as a dog trainer or horse breeder than as an artist. In any case, the practical, horny-handed farmers would have little time for a pursuit they would have deemed effete and, worse, unprofitable.

Fighting cocks was another enthusiasm of his for many years. He trained them for their bloody battles and spoke proudly of his success in this arena. Blackshaw’s father before him used to attend cock fights with Seamus Heaney’s father.

The artist and the colourist in Blackshaw no doubt saw the possibilities of their magnificent plumage and the riot of bloody colour that ensued when they were in action and he painted them regularly over his career. Rooster (guiding €40,000-€60,000) shows one of these proud creatures strutting his stuff. There’s no attempt at figurative exactitude (the proportions are beyond eccentric), but it captures the colour and energy of these avian warriors.

Rose Jane Leigh’s importance as an early pioneering Wexford landscape painter and her choice of studying in Antwerp placed her at the centre of the major art movements of the 19th and early 20th century, writes Mary Stratton Ryan