Eamonn Doyle’s portraits of Dubliners are unposed, untroubled by vanity and full of momentum, writes Stephanie McBride

Eamonn Doyle’s portraits of Dubliners are unposed, untroubled by vanity and full of momentum, writes Stephanie McBride

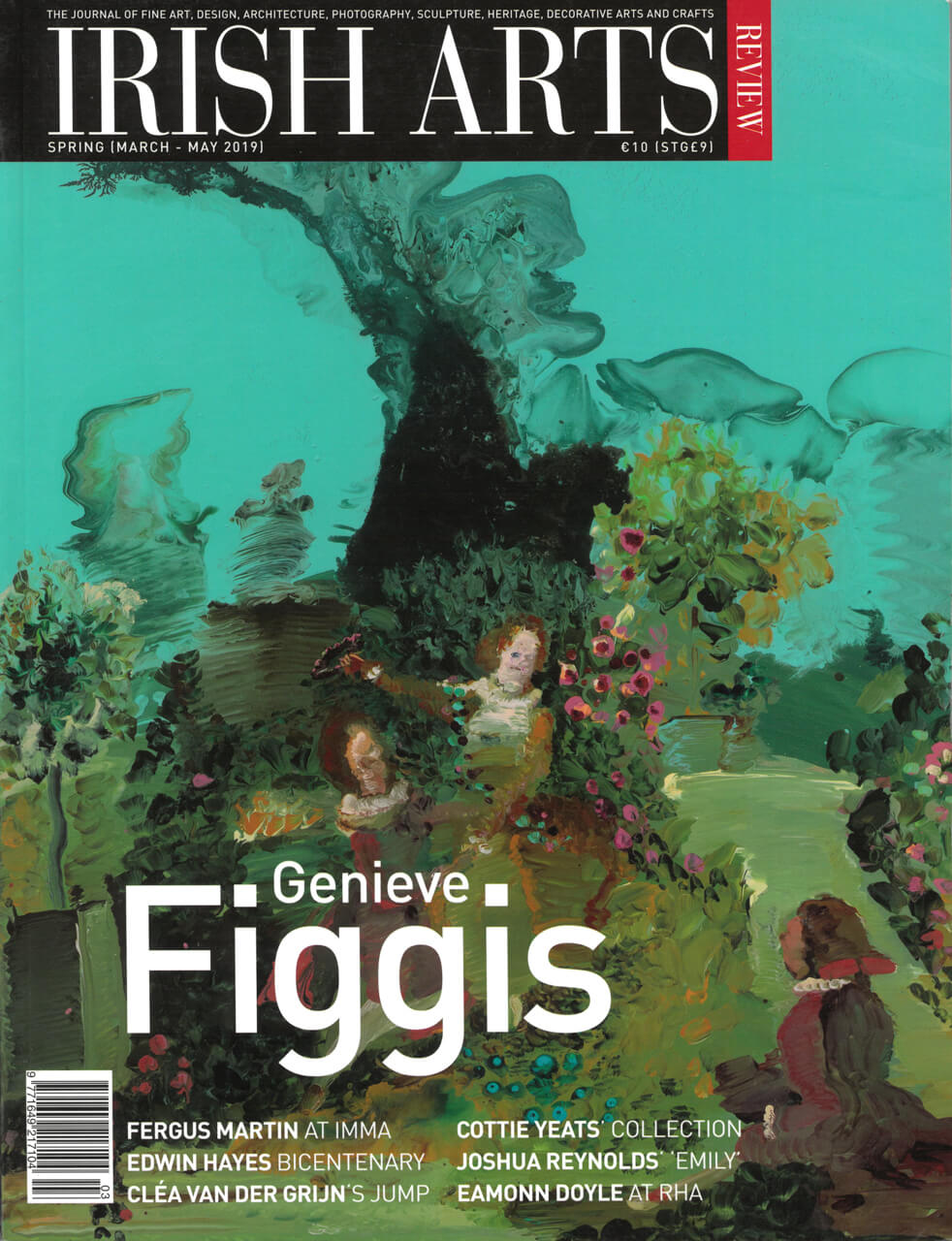

In spring 2014 on O’Connell Street in Dublin, passersby were captivated by an outdoor installation of large-scale photographs of people. Women in floral headscarves absorbed on an errand; others in crocheted woollen hats pausing for a moment; an old man in a moss-green knitted cap; a more urbane figure in a brown trilby; and a man bracing himself against the world and creating a pleasing contour with road markings (Figs 2, 3 & 4).

This was Eamonn Doyle’s first collection, titled ‘i’, 2014, and it demonstrated his acute observation of the play of curves and lines, and his considered choice of angle and perspective to avoid revealing any faces. This is a city’s people caught in their workaday routines, in studies that are intimate yet distanced and never put on. They are unposed, unsuspecting and untroubled by vanity. The collection captures the momentum of Doyle’s own stomping ground too; he lived nearby for many years and his family has business roots in the area.

As the capital’s major thoroughfare, O’Connell Street has a large quota of public monuments. But Doyle’s Dubliners are pared-back portraits of an unknown citizenry. The framing is anti-monumental as the elderly and lowly figures ebb and flow below the hard, haughty grandeur of the statues. The people are buffeted by unseen forces and currents, the Brownian motion and flux of the street. Viewed in situ, Doyle’s portraits formed an authentic alternative public sculpture. Though he acknowledges Beckett’s influences (signalled by the titles of his collections) and themes of transient, lone figures in a teeming world, another literary giant is not so far away. Edging into O’Connell Street is the statue of James Joyce, planted amid the noise and the hurry of North Earl Street. Joyce’s own Dubliners populated the byways nearby just as Doyle’s pedestrians walk, hover and linger there too. In a further link to Doyle’s Dubliners, Joyce’s personal favourite angle when being photographed was the back of his head, a type of shot and portrait that Susan Sontag once called ‘the poetry of the turned back’.

Despite completing a Diploma in Photography in the 1990s, Doyle’s working life veered towards music; he established indie record labels and the Dublin Electronic Arts Festival. This return to photography with ‘i’ was hurled into the limelight after Martin Parr lauded it as a startling and unique innovation in street photography. Doyle continued his exploration of the genre with two more photobooks, ON and End.

The second book in this trilogy, ON, 2015, part of a project with Niall Sweeney and David Donohoe (collaborating with Doyle on design and sound respectively), is a further exploration of contrast, pattern and shape. Working in monochrome allows Doyle to play with the potential of chiaroscuro, at times reinforced with silver inks. Unlike ‘i’, where the wider surroundings were mainly angled out, in ON the architectural context is central to the construction of the image. In one photograph a figure in a black jacket walks alongside Trinity College’s elegantly curved railings; Doyle’s angle captures the curious patterns and filigree literally carved by light and shadow on the human figure and on the rain-dampened pavements (Fig 1).

Switching back to colour, in End, 2016, he continues his Dublin odyssey. An overhead shot – by now customary – shows two little girls in flowery prints, their delicately tousled hair caught in a gentle breeze. It’s a fluid moment, in contrast to the street’s rigid yellow lines and harsh surfaces. Doyle’s developing sense of dynamics is even more highlighted in ‘Loop‘, with its study of the human figure in gradual motion, frame by frame. Against patterns of the gently curved balustrades and hard edges of adjoining buildings, an elderly man hunches his body against some invisible menace.

A marked departure in style, K, 2018, is a very personal elegy on his mother, Kathryn. In a shift away from urban Dublin to the West of Ireland, the landscape here is not as travelogue but elemental and raw. Strange phantom shapes haunt its bare terrain, some swathed in golden fabric, others shrouded in blues, reds, greens and pale greys. Their outlines resemble statues, a Madonna perhaps; but unlike conventional statues of hard, unyielding substances, these are fluid, amorphous energies wafting or hobbling in the air stream. The figures are ethereal yet grounded in a landscape, either frail and serene or muscular and contorted in a sinewy materiality. Just as Doyle’s Dubliners seem to be tugged and drawn by invisible forces, these spectral presences are pitched and tossed by unseen currents in an Aeolian dance (Fig 6).

In the same work, Doyle integrates handwritten letters from his grieving mother to her eldest son, his brother who died suddenly years before. Photography, as its etymology suggests, is about writing with light; and it is photography that underpins the link between these resonant media of letter writing and image making, each with its capacity to render absences. Doyle transforms his mother’s letters into densely layered textures. Anchoring the work is a haunting caoineadh/lamentation soundtrack by David Donohoe, with design by Niall Sweeney (Fig 5). Out of drifting phantoms – which are, like memory, fluid, liquid and nebulous – Doyle explores the expressive correlatives of mourning and memory, to create a startling, tender memorial and an extraordinarily powerful and nuanced artwork.

‘Made in Dublin’, Eamonn Doyle, RHA 15 March – 22 April; Mapfre Foundation, Madrid,

September 2019

Stephanie McBride is a writer, critic and curator lecturing on film, media and visual culture.

In spring 2014 on O’Connell Street in Dublin, passersby were captivated by an outdoor installation of large-scale photographs of people. Women in floral headscarves absorbed on an errand; others in crocheted woollen hats pausing for a moment; an old man in a moss-green knitted cap; a more urbane figure in a brown trilby; and a man bracing himself against the world and creating a pleasing contour with road markings.

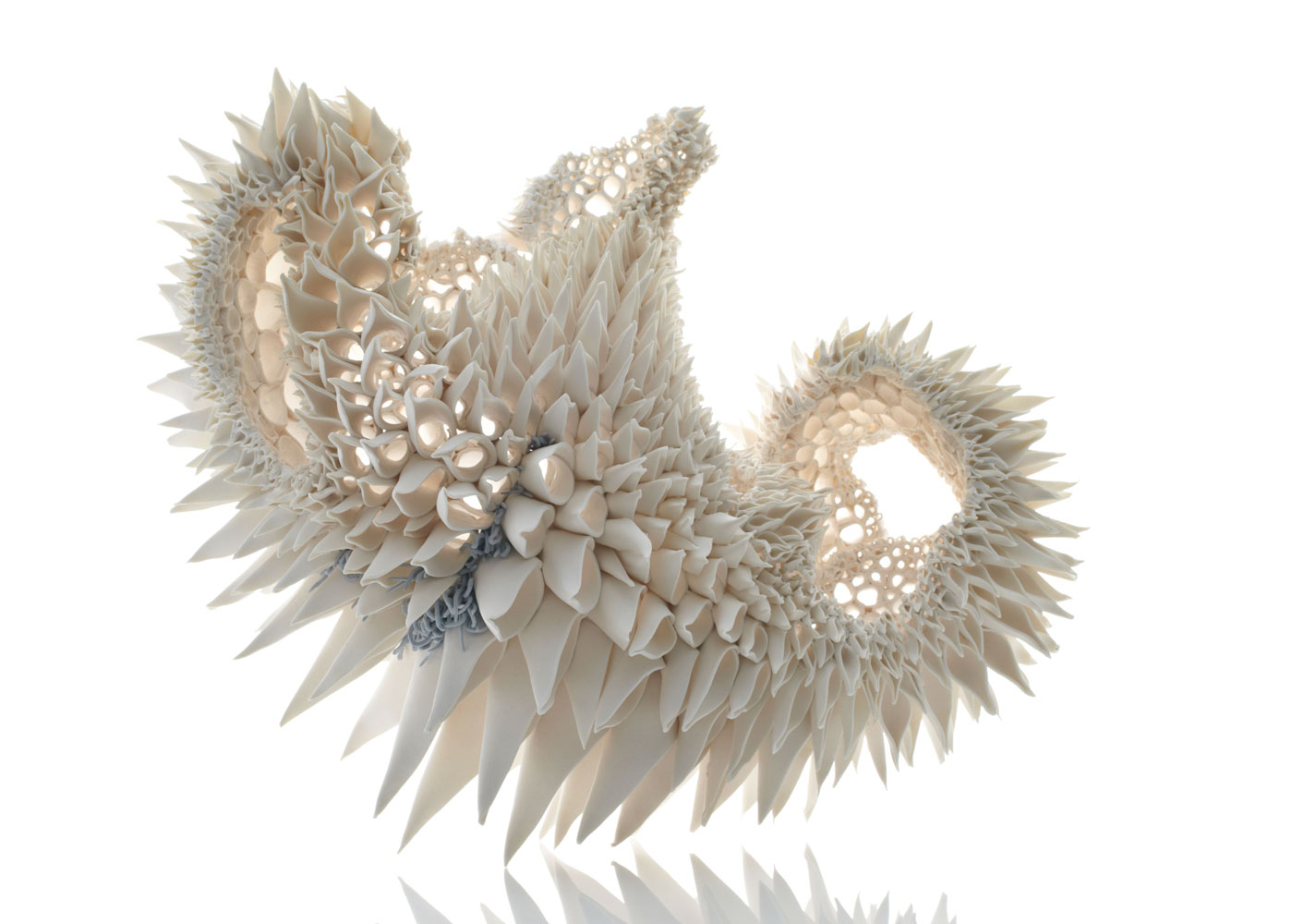

Research into theoretical principles across the fields of art, science and aesthetics imbue Nuala O’Donovan’s work, writes Mark Ewart

Rosemary Devereaux paints a picture of Mary Cottenham Yeats as a talented, resourceful artist in a variety of media