Kerber Verlag, 2021

Kerber Verlag, 2021

pp 104 fully illustrated h/b

€44.40/ £37 ISBN: 978-3-73560-734-8

Fiona Kearney

In his considerate essay in Jackie Nickerson’s substantial new publication, Field Test, the art critic Aidan Dunne describes the photographs as ‘slightly disturbing, as though they reach us from an uneasy future‚’, and it is hard not to view, and review, this powerful body of work through the lens of the recent pandemic. Although the majority of the images presented throughout the book were created by Nickerson in 2019, they have an eerie and prescient resonance with the recent impact of Covid-19 on both individual and global relationships.

Perhaps most chilling is the direct reference to infection control and health measures in images entitled Virus I and Virus II, where we see colour photographs of people in PPE sheathed in see-through plastic bags, or in Virus III, where the colour photograph lies behind printed cardboard packaging, a signal of all that was yet to come and how the world would so quickly shift to isolated local living, screen-mediated interaction and parcel-dispatched purchasing.

Yet the artist’s broader psychosocial observations emerge as the most potent adumbration of our suddenly changed collective environment. From the way in which Nickerson positions airports as industrial spaces viewed through monitors and surveillance footage rather than as sites of human interaction that should host the frenetic bustle of international travellers, to the focus on makeshift masks and protective clothing, it is as if Field Test was a commissioned response rather than a prophetic precursor to a disease unravelling human connectedness across the world.

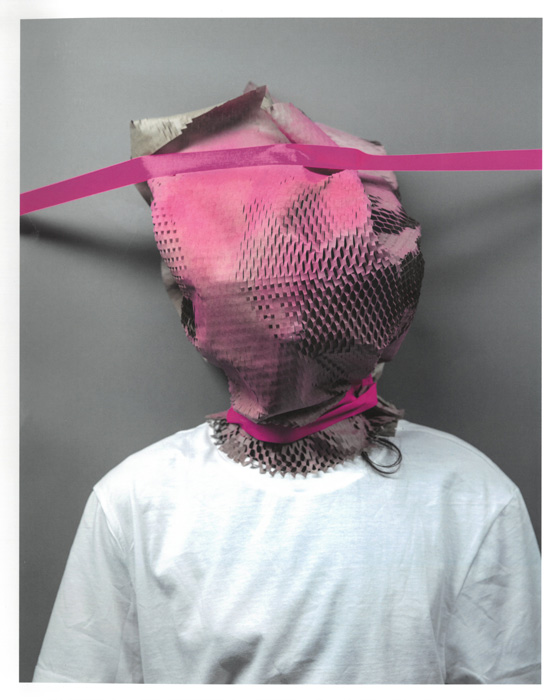

The photographs primarily depict individual human subjects in isolated poses, each person bound, swaddled and often smothered in a variety of wrapping and fabrics, which has the effect of transforming the figures into sculptural forms. Nickerson acknowledges in her conversation with Dan Thawley at the beginning of the book that she chooses her sitters for their ‘proportions, scale and height‚’ and, under her direction, the bodies indeed become another material for her to construct and control. The correlation with Nickerson’s editorial fashion work is clear – her subjects are models to be directed, not muses to inspire, objects wrapped in the leftovers of commercial consumption and linked by association to domestic articles.

her subjects are models to be directed, not muses to inspire, objects wrapped in the leftovers of commercial consumption and linked by association to domestic articles

A rare moment of levity is the gaudy-coloured configuration of pink, green, blue and yellow clothes pegs in Grip that links these meagre household items and her human subjects as equally impoverished pin-ups. These anti-portraits are also informed by the industrial rooms of food production that punctuate the book. These locations appear as documented places as in Tomato Plants II, where we are invited to peer into hothouse farm environments, and as pictorial objects as in Abattoir, where a postcard-size image of meat hanging in a slaughterhouse sits inside a polypropylene food container – a photographic mise en abyme that underlines the sense of recurring conceptual as well as physical distance that permeates Nickerson’s compositions.

For all the suffocating isolation and synthetic materials that dominate Nickerson’s image-making, there is a forlorn and folksy feel to the way in which the subject/objects have been assembled. Like the weeds that she captures under fluorescent lighting, she seems to suggest there is still room for individual growth and expression, even as we remain covered in reams of plastic.

Fiona Kearney is Director of the Glucksman, University College Cork.

Peter Somerville-Large recounts the history of the National Museum of Ireland’s significant ethnographic collection, last displayed over thirty years ago

Eileen Black recounts the life and work of Post-Impressionist painter, Georgina Moutray Kyle

Olivia Musgrave’s interest in the Classics greatly informs her sculptures, writes Peter Murray