This month Dorothy Cross delves into our national collections to create a show for IMMA,here she tells Brian McAvera ‘Sometimes I need extreme new experiences to find new directions,’ while the show continues into March 2015

Brian McAvera: You’ve been showing recently at Turner Contemporary in Margate, exhibiting video, photography, photographs and sculptural pieces, many of them connected to the sea. Can you take several works from the current show ‘Connemara’ and show us how they were developed?

Dorothy Cross: Everest Shark (Fig 3) came out of an invitation to make a show about time for Croft Castle in Shropshire England. So you have time as a premise. I have great respect for sharks. Little is known about them. I was searching a long time for a shark. I eventually found one frozen in a fishmongers in Carlingford, a beautiful, two-metre-long blue shark. I then delivered it to the foundry where a mould was made of it. Then we made a wax of Mount Everest. The shark evolved to its present form 100 million years ago. Mount Everest, the highest peak on our planet, rose to its height merely 60 million years ago. I wanted to place the ridge of Everest along the back of the shark like an alternative dorsal fin. The work is simple really: it is about time and evolution. Trying to meld the mountain to the shark was tricky but in the end was beautiful. The muscle of the shark was beginning to subside so we met the Himalayan mountain ridges with the skin of the animal so that it appears the structure of the highest peak of our planet is emerging from the shark’s back. You look at it but may not recognize what it is at first. It’s almost a comforting piece because, while nobody thinks of a shark as comforting, it has survived longer than almost anything else on this planet. I’ve dived quite a lot with sharks: most will swim away when they see you or just hang round and watch.

Tabernacle, however was more difficult to make (Fig 1). The title came later. The piece was in gestation for years. I had a currach from the opera I worked on for ENO’s Riders to the Sea. It was lying upside down in my field for three years. At one point I thought that I’d make this currach into a hut. Very often I have structures placed centrally in a show, working architecturally like a pivot for the surrounding sculptures, a grounded space for the viewer. At Turner Contemporary, I built a structure and inverted the currach so that it functioned as a roof. I had found old black-blue linen blinds. They functioned as provisional walls which can be pulled up and down and create a sense of security. I had a round frame like a porthole in my studio which I used as a window. And a set of old wooden stools which I placed like little school benches. Old bottles of holy water remained attached to the bow of the currach where fishermen would have placed them for protection at sea.

For the piece I had intended to make a hammock lined with a shark’s skin. Then, when I skinned the blue shark – I did it myself and it was a difficult and repulsive job – it shrank and I was stymied! I knew that I wanted to project a video of a sea cave somewhere in the show, and when I placed the projection in relation to the currach – wham! It worked. The structure looks like a little cinema or epidiascope lined up towards the interior of a beautiful black shiny cave where water and light emanate towards the camera. The sea cave in the vertical video is located at the bottom of my land and is only accessible about ten days a year when calm and at very low tide. I thought later, it’s like a tabernacle. One definition of a tabernacle is a non-permanent structure located in a desert as a place of worship. Another, is a groove in a yacht into which a mast fits. And the Catholic version is a small golden receptacle on the altar of the church.

BMcA: What are you working on at the moment?

DC: I’m working on a book called ‘Connemara’, of works made since I came to live here. The show that was at Turner Contemporary is currently on view at the RHA. I’m also working on an exciting project where I was invited to select works from the National Museum, the Natural History Museum, the National Gallery, IMMA, and the Crawford. It will be shown in the Garden Galleries of IMMA in June. I’m doing a show in Lismore in September in St Carthage Hall. There will be a new piece for that, and I might have a show at the Kerlin in September. Some years are busier than others.

I would hate to think that I’m going round in circles. Maybe we are just limited by being humans! Sometimes I need extreme new experiences to find new directions – like bringing the fingertip bones of a hand and inserting them into five, black-lipped oysters in a lagoon in Tahiti to see if the animals would cover them with black pearl. What’s interesting about the museum show, which is called ‘Trove’, which implies found treasures, is that the selection process is in some ways so random, about taste and relationships. I’m very drawn to the non-celebrity works – the storage racks, paintings awaiting restoration, or those without provenance. There are big lumps of ancient bog butter in these wonderful urns. I want to put a beautiful Patrick Scott next to the series of ancient Celtic golden spheres from the National Museum. As artists I think we have to push the parameters, to push our intelligence, imagination, and our bodies.

BMcA: You have worked on a number of Public Art Projects, such as Ghost Ship and Chiasm. In projects like these, what do you see your function as?

DC: The function is a trigger. You keep having to trigger things to get them to happen. If the idea is good, it’s inspiring. Ghost Ship was a simple idea, but it was a monster to make. In the beginning everything was against us: harbour rules and regulations, insurers, money and so on. If you have enough people around you who believe in it, you’ll get there. In the end it worked, but it took the best part of two years to get it out there. With Chiasm, Fiach MacConghaile, who ran the Project Arts Centre then, came to me and asked if I had any ideas. I said I love handball alleys and the seapool called Worm’s Hole on Inis Mór – and he nurtured that project to fruition. The seapool was formed geologically and contrasted with the manmade structure of the handball alleys. I put two opera singers in two handball alleys singing about love and loss ‚Ķ. A great many people worked for very little money to make it happen. It is one of my favourite works.

BMcA: There’s a streak of the surreal that runs through your work: one might think of Meret Oppenheim’s fur cup, Object, (1936), Dorothea Tanning, some of the photographs of Lee Miller or Dora Maar, indeed many artists from the 1920s, through to the 1940s in Europe and the USA. Do you yourself make a distinction between Surrealism, and the surreal?

DC: My work has been shown under the label of Surrealism, but I do not like categories. At the opening of Tate Modern my work Virgin Shroud (Fig 5) was placed next to Salvador Dali’s Lobster Telephone (c.1936). I was once asked to speak at the Salvador Dali Museum in Florida. I said I would get back to them later as I am not a big fan of Dali. I then went for a walk on the beach and happened to find a lobster pot with a dead sheep stuck in it and because it seemed so Daliesque I phoned the curator and said I’d do the talk. I adore Meret Oppenheim’s fur teacup which is an iconic piece: it’s about the domestic meeting nature.

BMcA: Surely it’s about sexuality?

DC: That’s only one part of it. When art is good it affects one in a real sense. I know that some of my works can disturb, but disturbance can be good. I wouldn’t describe my work as surreal, though I can see why people might. I am interested in trying to get back to the elemental, to brass tacks. When I was working with the cows’ udders, I would twist, dry, be repulsed, become familiar with them, and transform them into something else. The viewer has the confrontation of strangeness, immediately. It can take a while for someone to relate: that’s what I’ve learnt as I’ve got older.

When art is good it affects one in a real sense. I know that some of my works can disturb, but disturbance can be good

BMcA: In the 1990s, using stuffed snakes and cowhide, you produced a varied body of work which invited deconstruction in terms of sexuality, mythology and, perhaps, cultural difference. How do you view the work?

DC: When I first came back to Ireland I was very isolated from what was going on here. The artists I connected to most were Kathy Prendergast, whom I greatly respected, the City Maps were such new territory. Helen Chadwick influenced me. Willie Doherty I worked with and taught with and have an immense respect for his work, as for James Coleman’s.

The early works in ‘Ebb’ related directly to psychoanalysis: Playing with the balance of animus and anima. I never felt the work was about claiming strength for women as it is sometimes described as (Fig 6). I was looking at both sides of the fence and I was conscious of the predicament of being male. I remember as a child watching my brother, through a window, fighting with a local gang and even at such a young age being aware and grateful that I wasn’t a man, that I would not have to go to war!

BMcA: Patrick Murphy, who had been director of the Douglas Hyde when you showed ‘Ebb’, moved to the ICA at Philadelphia and gave you a show there ‘Power House’. How important was this for your career?

DC: For me the importance was that it was a bigger arena than the Douglas Hyde. I was given the space to develop something new. I usually find that one project leads to another. Most of that work from the show was destroyed. I never approach these shows in terms of selling. Museums and more experimental places are the ones interested in my work. They are interested in creating new relationships with their spaces also. For ‘Power House’ we brought the entire control panel from the derelict Pigeon House power station in Dublin to Philadelphia and then brought it back again.

Is there luck involved in getting the next invitation? I am not sure. In ways the work is outside of oneself. I do have a certain amount of blind faith in the work because I usually get so excited about it myself. Once it is done the relationship ends – it is over. Of course the invitations are important for a continuum of work.

BMcA: You were born in Cork in 1956, when the Republic was still in the doldrums, and most things were clerically controlled and conservative. What are your memories of these early years, what did your parents do, and how far did river and sea impinge on your imagination in those early years?

DC: My upbringing was relatively privileged. We had a house in Montenotte in Cork; our house looked down on the river Lee from a hill, and you knew the river was a portal into the ocean. We spent three months of the year in a house by the sea that we called The Hut. My father had had a hut by the sea when he was a bachelor, from where he sailed boats. He met my mother on a yacht in West Cork, so the whole parental connection was bound up with the sea. My mother was seventeen when she met him. She was born in Cork but brought up in London. He was thirteen years older and they married when she was nineteen.

I published a two-volume visual memoir Montenotte and Fountainstown (see review in IAR Spring 2013, p. 137). My mother had a spare aesthetic: she would have a Japanese vase holding a single camellia perfectly placed in a room. My father had inherited a business, Cross & Sons Garage, where they originally made carriages. It was said that Henry Ford himself came to visit my great-grandfather but grandfather said the Ford would never catch on, so Ford went to America! My father didn’t want to sell cars, but he did maintain access to the sea. After he met my mother he built a house near to The Hut in Fountainstown where we lived three months of the year, swimming and fishing – real freedom.

When I was ten my brother Tom started coaching a swimming club in Cork. He encouraged me, and I started training competitively from the age of eleven to seventeen. My sister Jane and I swam for the province and then for Ireland. In the element of water we were very happy. We trained 360 days a year. Yes, the discipline does translate to my work. We’re all very disciplined, me my brother and my sister. I missed the Munich Olympics by 0.1 of a second. There is a theory that in training one goes into hurt, pain and agony. I went into hurt, occasionally pain but never agony – which is necessary to really succeed.

As kids we used to watch films like The Old Man and The Sea. Later when researching a project in New Ireland in Melanesia I met an old man who was a shark caller – and I told him the story of the old man. As a child that story, for me, was desire. It involved risk, loneliness and adventure. The desire was always there to eventually live by the sea.

Our parents gave us freedom. They had a real appreciation of life. Neither really did what they wanted to do. My father didn’t want to run a garage, and my mother wanted to be a doctor but became a housewife, so as a result they were liberating to the three of us. As a kid, access to art was the Texaco Art competition. One teacher encouraged us to enter the Texaco Children’s Art Competition each year. Even through the swimming I kept painting, as a child, but I never painted as an adult!

BMcA: You have lived in cities but have returned to live and work outside of the city. Why?

DC: Desire! Now I know for sure that nature works for me: if I’m working in the studio or at the computer, and then walk out of the door and see a hare, or a dolphin, it brings everything back into flow, a balm. It explodes the neurosis of the city.

BMcA: You’ve always expressed a strong interest in Joseph Beuys, yet his educational strategies were risible, he regarded women, and especially female students as inferiors, and recent research has demonstrated that many of his exploits are myths. What is it about Beuys that attracts you?

DC: What attracts me? I wrote a bit about the deaths of Beuys and Warhol in the end of the 1980s‚Ķ neither of whom I’d be in love with, but if you put the two of them together! Beuys talked about essence and energy. I went on a fieldtrip with students when I came back to live in Ireland where they were being directed to paint the landscape. I remembered the image of Beuys’ hat floating in a bog. What it said to me was, we are a part of the bog, and we are not just looking at it. I loved that. Certain pieces of work – the fat on the chair for instance – I loved. If you could clone Beuys and Warhol you’d have something extraordinary: Warhol being the apparently superficial player who put soup cans next to suicides and Beuys the one who tried to get into the essence of materials. When I used to visit MOMA I would always go to see Meret’s teacup and Beuys’ sausage. I loved the idea of the sausage in MOMA! Did they replace it at intervals if it shriveled? And Duchamp’s’ Bicycle Wheel (1951) was nearby. My head would be with Duchamp but my heart would be with Meret, and the rest of me with Beuys. But you brought up Beuys not me. He is not that important‚Ķ people like Andrei Tarkovsky were much more influential but that’s another interview!

Now I know for sure that nature works for me: if I’m working in the studio or at the computer, and then walk out of the door and see a hare, or a dolphin, it brings everything back into flow, a balm

BMcA: You spent a fairly short period at the Crawford Municipal School – Foundation (1973-74). Why was that? How did you find it? And what impelled you to enter an art college in the first place? DC: When I left school it was either do art or go to university. There was a seam of academic snobbery in the family so there was a certain amount of pressure for me to go to university. My brother (who was also my swimming coach) was a scientist. I sometimes went with him on fieldtrips, and was fascinated by his life as a zoologist. In the end I chose art. Since then I have realized that one has the best of both worlds in that artists can access many territories. That’s how I got into art.

At the time I believed that you had to leave the country to do art, so I wrote to a whole lot of colleges, from New Zealand to Iceland. I reasoned that, as with swimming, there would be scholarships to help study abroad. I left things late and so did a one-year Foundation Course in the Crawford. I was a little younger than the sculptor John Bourke’s group. I did one year there, where most of the time was spent sitting drawing the plaster casts in the sculpture gallery, the Belvedere Torso or the Laoco√∂n. That’s where I was happiest. Then my uncle who lived in Leicester sent me a syllabus for the Polytechnic there and that is how I ended up doing a BA in 3D Design from 1974-77. I didn’t really know what I was doing. There was nobody there to advise me so I ended up in Product Design by mistake and nearly committed suicide! So I switched and went into jewellery and felt more confident. Then the jewellery began to become more sculptural. In the Crawford I was not really aware of the broader contemporary art context. Jack B Yeats’ paintings hung in the houses of my aunts and uncles. For some reason I believed that art existed elsewhere.

BMcA: What kind of education did you get at Leicester?

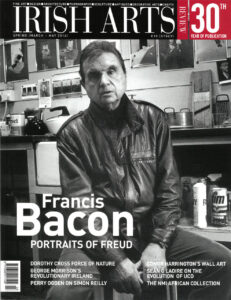

DC: I was at Leicester at the time of the Birmingham bombings. I was learning how to make. Sometimes making gives you the time to discover what the thing is. I saw Francis Bacon, Giacometti, Hockney, Richard Deacon, Anish Kapoor, Wentworth and Cragg in exhibitions in London. It was the first time that I had started looking at sculpture. I was reading Camus and was also being obsessed by Beckett. Leicester is a pretty miserable Midlands town, and it was a darkish time in terms of the bombings, a transition time. I read a lot and went to London for weekends. After the BA I worked for a year as an apprentice for a jeweller in London. I didn’t want to be a jeweller, but I learnt the skills, sold things to Liberty’s to make money, and that kept me going. I didn’t want to be in Ireland. I had applied for an MA in San Francisco Art Institute but the forms got lost!

BMcA: You were at San Francisco Art Institute between 1978 and 1979 for ‘non-degree study’ and then again in 1980-82, this time studying printmaking. How useful was the American experience to your career; did printmaking leave any mark on your work; and what kind of art did you see in America? How did you support yourself?

DC: San Francisco was amazing – such a contrast to Leicester. I went to SFAI and began on a non-degree course. I found I loved the energy of the place. Why printmaking? I loved the fact that the process is so slow. The tutorials were rigorous. They’d have seminars where I had to learn to talk about art. I read Beckett’s plays and made prints based on the plays. Attempting to create the sense of the play with subtle changes in position and colour. Beckett gave me a form on which to hang my work. I could hide behind the plays so as to use another structure of language to speak about the work. Beckett impressed the American tutors. In the end the work burst though into big images of the body: big matriarchal things that are better forgotten. I worked in a shop and in a fish restaurant to support myself. I had no money to go, so I wrote to Irish companies asking them to sponsor me. In the end a cousin of my mother’s funded me to go for my first year. I was down to my last $25 when a businessman phoned me at midnight, said he’d just found my letter in his files, and that he’d like to help. He sent the money for my fees. It was such a wonderful gesture of faith. I had never met him at the time. Years later I asked him if he wanted credit for his help and he said no. I tell this story to students as I believe there are wonderful people out there, who do believe in art, and are willing to support something that is not necessarily fully formed yet.

BMcA: You had four solo shows in the 1980s, two at Triskel, one each at Hendriks and the Octagon in Belfast, before ‘Ebb’ at the Douglas Hyde effectively launched you in 1988, the year of the SSI Sculpture Conference in Dublin and also of Rosc 1988. It was also the year in which you got the P.S.1 award. How would you describe your journey?

DC: I knew that I wanted to come back. It was either that or go to New York and wash dishes, so I came back. I was only twenty-seven. I had been away for nearly ten years. It was 1983 and it was then a case of survival. I didn’t know anyone in the art world. I knew writers and philosophers. I worked in a basement flat, went on the dole, and reacted a little to being back. I started making sculptures called Contraptions. It was the time of protests about divorce and abortion. The Contraptions were about diminishing power; the collapsing voice of authority. I think they were very funny! I spent hours making them out of thin painted plywood. Most of them got broken up. Cecil King bought one called Gothic Chair: his only worry was that the cat would break it!

The exhibition ‘Ebb’ at the Douglas Hyde was the opening of a big lock. It was the first time I was given real space

BMcA: It has been suggested that events like the Abortion Referendum (1983) and the Divorce Referendum (1986) sparked an interest that developed in your work, which was about sexuality and the Church. I wonder if it’s not more complicated than that? While Ireland was still repressive in the 1980s, you must have come across far worse examples of repression, sexual or otherwise in South America, Japan or India. What is your view?

DC: Yes it’s more complicated than that. Things were changing that is what was interesting. I am interested in change even if we do not know what that change is. To come back to Dublin and see the ‘hooha’ was funny, but not funny. Maybe it was about breaking back into Ireland as an adult. I’d just come out of the MFA where I had been hiding behind Beckett, and now I was looking for my own terrain. It was a big thing for me to come home. I was terrified. I could see that the contemporary art world hadn’t become established, and I knew it would be difficult to survive. This interview is like the first day at the shrink’s! Having to dredge through old work. The exhibition ‘Ebb’ at the Douglas Hyde was the opening of a big lock. It was the first time I was given real space. I did not believe that I could fill the Douglas Hyde and said to Patrick Murphy at the time, ‘I can’t do it’. He said, ‘You can’. I respect him retrospectively for that. I adored doing it. It was the first time the architecture ‘held’ the work. The whole thing was a liberation. It was the first time that I made works which related to each other, which I still do, and the viewer becomes the catalyst, a participator. The sculptures were like characters: Mr and Mrs Holy Joe, the Erotic Couple ‚Ķ.. I made the show just after I read John Updike’s Couples, which I loved.

BMcA: After San Francisco you travelled a lot, in North and South America, Japan, India and Nepal. What were you looking for, and what did you find?

DC: I didn’t know what I was looking for and I found a lot. I never know what I’m looking for. If you’re going to go anywhere you have to hope you will find something that will be a surprise. With Japan it was the aesthetic, and my mother influenced me on that one. We had Japanese prints on the wall. South America had always intrigued me: the Incas when I was a kid. I went to India with a boyfriend who was studying Indian theatre. The temples were an extraordinarily fascinating part of it, a completely seething world of the sacred and the mundane: people washing saris and hanging them up next to ancient sculpture; a relationship between past and present, between the sacred and the secular. Visually it was one of the richest places I’ve ever been to.

BMCA: Is your career affected by where you live?

DC: I need to be by the sea and then I need to come to cities, have dinner with friends, and go to the movies, but I don’t think of ‘career’. I sometimes think that I don’t make art at all, and then you come across all of this stuff. I think as an artist you grow by making the work. If it’s good it’s life-changing for you, and then you can move on. It’s like the rings of a tree. If there were more rainfall in a certain year maybe the work is better!

All images Courtesy Kerlin Gallery, Dublin and ©Dorothy Cross.

Trove’ IMMA, Dublin 3 December – 8 March 2015.

Brian McAvera is an art critic.