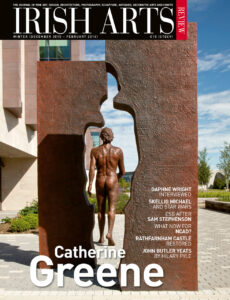

Recent excavations at Rathfarnham Castle have brought the former inhabitants into focus, prompting Simon Loftus to recall some vivid episodes from the family’s history.

Adam Loftus ‘builded his howse at Rathfernan’ in 1583 as a domestic fortress, then filled it with treasures. A magnificent silver cup, made from the Great Seal of Ireland, stood before the Chancellor-Archbishop when he dined in ceremony, and the head and antlers of a giant elk, dug from an Irish bog, hung on the screen opposite. ‘Basins and Ewers of pure Silver’ were proffered to his guests to wash their hands, and ‘great standing white Bowles, which were brought by Mr Newcomen out of England,’ were displayed for their admiration. Adam feathered his nest like a prince. The cup survives, and a portrait of the old man (Fig 2), but we only catch glimpses of life at the Castle in the decades following his death – and the outbreak of civil war in 1641 put an end to luxury.

Rathfarnham’s garrison during those troubled times was commanded by the eccentric orientalist Dudley Loftus, and the Castle provided shelter to numerous refugees from the fighting, including Dudley’s friend John Ogilby, Ireland’s first theatre-manager. Ogilby was almost killed by an explosion in November 1642, having tried to make a firework to celebrate his birthday, but survived to enjoy long conversations with Dudley Loftus, which rekindled his interest in classical texts. When he returned to England, damaged and destitute, he ‘became such a master of Latin and Greek, that he translated Virgil and Homer, [and] paraphrased Aesop’s Fables’. According to his own account, Ogilby’s translation of Virgil was begun in Ireland, ‘bred in phlegmatic Regions, and among people returning to their ancient barbarity.’

The Restoration, in 1660, brought a radical change of mood. Rathfarnham passed to another Adam Loftus (later Viscount Lisburn) whose life was notorious. He killed a man in a duel, brought a giant Irish wolfhound to fight at the court of Charles II, was a crony of the great embezzler, Lord Ranelagh, and was married twice – to beautiful but dissolute women (Figs 3&4)whose portraits were painted by Lely and Kneller and lives laid bare in satirical verses (the scandal sheets of the day). The Earl of Donegal marvelled at ‘Addy’s’ extravagance (‘His wedding was very public. I hear the furniture of the wedding room cost £1000.’) and others criticized his drinking, particularly when Adam went on campaign in the war of the two kings. ‘He passes his life at play and the bottle; a little wine befuddles him.’ His Lordship’s death matched the wildness of his life – head blown off by a cannon ball when emerging from his tent at the siege of Limerick.

All of which was archival gossip until September 2014, when a hoard of 17th-century artefacts was discovered at Rathfarnham Castle, buried under the stone floor of one of its massive corner towers. Chinese porcelain, clay tobacco pipes, drinking glasses, a foldable toothbrush, chamber pots, a tiny perfume flask, Italian cosmetic jars, fashionable shoes, coins, wax seals, marrow spoons, an arm from a child’s doll, a rusty steel breastplate and the remains of costly foodstuffs – tea leaves, cherry stones, apricots and peaches – all remarkably preserved in a sealed cavity filled with mud. And this intriguing medley could be securely dated – because hand-blown wine bottles were found, embossed with the initials of Adam Loftus and the year of the ‘Glorious Revolution’, 1688. It was vivid testimony to a life of luxury, fashion and domestic display.

Adam’s death left his daughter Lucy as the sole heir to his estates, and six months later she married Tom Wharton, who was skewered by Swift as a man ‘without the Sense of Shame or Glory, as some men are without the sense of smelling.’ Their life at Rathfarnham mixed extravagance, scandal and politics until 1714, when Wharton died of apoplectic fury following his sixteen-year-old son’s elopement with a girl of no fortune. Young Philip outdid his father in profligacy, squandered his fortune and died a bankrupt abroad. In 1723 Rathfarnham Castle was sold.

It was not until 1767 that the Castle returned to Loftus ownership, when it was acquired on behalf of the ‘idiot’ Earl of Ely by his uncle Henry Loftus – who inherited his nephew’s estates two years later. Henry was a man of grandiose self-importance but had one great quality that even his contemporaries acknowledged, ‘an unbounded passion for improvement and a skill equal to that passion.’ With the death of his nephew the new Lord Loftus at last had the resources to express this talent to the full. He decided to transform the Elizabethan castle into a magnificent setting for hospitality, display and political intrigue.

Rathfarnham had already been modernized by its previous owners (Archbishop Hoadley and his son-in-law, Bellingham Boyle) and was no longer the dark fortress built by Adam Loftus in the 16th century. It had acquired tall Georgian windows, a grand staircase and a new kitchen wing. There were fine gardens, a beautiful well-wooded park and ‘a great many fish ponds, where is the largest carp ever I saw in my life’ – as Lady Anne Connolly wrote to her father in 1733. But this was not enough – Henry wanted to refashion everything in the latest taste and was impatient to get started.

Within a few months of his nephew’s death he was pestering Sir George Macartney, the Chief Secretary, for permission to import two or three plates of French looking glass – ‘as they make them of a larger size than is made in London’ – and he decided to employ two of the most fashionable architects of the day to transform the house and embellish the garden.

Sir William Chambers and James ‘Athenian’ Stuart were chalk and cheese. Stuart combined a passion for the primitive vigour of the Doric order with a love of movement, lightness and exquisite colour. Chambers preferred classical Rome to ancient Greece and was rigorous, sometimes dour, in his formal brilliance. Initially it seems that Stuart was commissioned to design a suite of family rooms on the south side of Rathfarnham while Chambers was allocated a couple of grand reception rooms on the north. Chambers dawdled but Stuart (who had never worked in Ireland) was determined to prove his worth. By August 1770, when the young Lady Shelburne paid a call with her husband, the renovations were under way.

We found Lord Loftus and Miss Munroe his niece at home. She is a celebrated Beauty and very deservedly so, she walked about ye shrubbery with me and showed me a flower garden that is making for Lady Loftus and when we came home sent for a harper to play for us. Lord Loftus walked about with my Lord and showed him his Improvements. The house was an old one of which only the shell is preserved and some of the rooms within he is fitting up after the designs of Mr Stuart’s. There is a great deal of French cabinet work and Lord Loftus showed me several fine pieces of his turned ivory which he bought from Spa and other expensive toys.

Those ‘expensive toys’ may have allowed Lady Shelburne a moment of superior disdain, but she was certainly impressed. Having a harper on call to entertain your guests was a sign of princely magnificence – even when used as a stop-gap for conversation. The result, with atmospheric appropriateness, is a house in two halves, reflecting the character of their designers. Stuart’s south-facing rooms are light and wonderfully elegant, despite the vicissitudes of time. Little survives of the Long Gallery’s 18th-century decor except its ceiling, but the brilliantly original plasterwork reminds me of Japanese fans and the recently rediscovered orientalism of Palmyra. The small Drawing Room on the floor above has also lost most of its original features, including the grisaille wall decorations shown in the background of a family portrait by Angelica Kauffmann (Fig 1), but the ‘Breakfast Room’ next door still has a lovely ceiling in Stuart’s favourite greens, framing roundels of fat cherubs masquerading as the four seasons, while a small, near-perfect cube – the ‘Gilt Room’ – glitters with brilliant combinations of gold, cream and delicate sea green, highlighting the symbols of the gods that circle the ceiling. Elegant door-cases – framing doors of Cuban mahogany with intricate fittings – and a subtle brilliance of colour contrast quite markedly with the more severe formalism of the north-facing rooms attributed to Chambers. But I think it must have been Chambers who designed one of the finest features of Rathfarnham; the lovely external staircase, linking Gallery to gardens. On the south side of the Castle, held within the clasp of two massive corner towers, this double flight of stone curves down in a perfect semi-circle, suspended in the air.

Dominating the Gallery was a vast family portrait by Angelica Kauffmann, painted in 1771 (Fig 1). The setting is lovely – an interior at the Castle, with a view to the garden – and the iconography is evocative of the Holy Family, but the overall impression (glances, gestures, relationships) is curiously uncertain. Henry and his wife pose majestically in the scarlet and ermine robes of the Irish peerage as an Indian page hovers nearby, carrying a tasselled cushion on which rest the coronets of the newly created Earl and Countess of Ely. The servitude of this ‘young black boy from the Malibar coast’ – who is said to have accompanied a gift of ostriches to his lordship – is echoed in the lowered head of Dolly Monroe, standing on the left of the picture, to whom Henry draws our gaze as he glances with somewhat tentative affection towards his unsmiling wife. Dolly was the sacrificial lamb, soon to be anointed, because her aunt (Henry’s wife) was manoeuvring to marry her to the recently widowed Viceroy, Lord Townsend. Her sister Frances, seated at a keyboard, plays the role of John the Baptist, as she points to the words of a song. But the traditional text of sacred imagery (Ecce Agnus Dei) has been replaced by a warning, for the music lies open at an aria from a popular opera, La Buona Figliuola (‘The Good Girl’), which begins: ‘Away, away, Sir, I will allow no-one to touch me.’ Fortunately for Dolly, she escaped her fate and was married to a man who loved her. This wonderful picture, which ought to be restored to Rathfarnham Castle, is now in the National Gallery of Ireland – and a Reynolds’ portrait of Henry Loftus and his second wife can only be viewed at Upton House in Warwickshire (Fig 5). Almost nothing remains of all that filled the house in the days when so many people applied to visit that Lord Ely had to organize a weekly opening.

For a brief while, after Henry’s death in 1783, his heirs continued to live in splendour, but they lacked his taste and cared only for their own aggrandisement. Gradually the contents were dispersed and the Castle abandoned. Around 1850, the Castle was purchased by Lord Chancellor Blackburne whose family continued in residence until 1913 when it was sold to a firm of Dublin builders. They turned some of the demesne into a golf course, divided most of the rest into housing plots, and sold the Castle with a little surrounding parkland to the Jesuits. When they moved out in the 1980s the property was sold for speculative development and at one point it seemed that the Castle itself would be demolished. There was a huge local outcry and eventually, after a long campaign, the Office of Public Works stepped in and saved the Castle for the nation. It has recently been extensively restored but for a sense of what it was like, centuries ago, we depend on the eyes of others – on William Jones who painted a large landscape of Rathfarnham in 1769, or Angelica Kauffmann who showed a glimpse of the gardens in the background of her family portrait – and on the 18th-century visitors who described the place in their letters and diaries. They praised the ‘beautifully stuccoed, gilt and painted’ ceiling of the porch, the ‘elegant paintings and China Vases,’ magnificent mirrors and furniture that once adorned the Castle, and the gardens – with their hothouses, ripening exotic fruit, and the ice house, filled in winter when the lake was frozen. And the aviaries, menageries, fishponds and pavilions that formerly dotted the grounds.

‘As far as the eye can reach there is nothing but wide green open or shaded lawns and woods of chestnut, beech, elm and every variety of tree. On the river facing the house is a picturesque mill-wheel, and a pretty bridge carries one safely across the stream to an old mill house.’ Now, that vast and handsome demesne has shrunk to a plain municipal lawn surrounded by meanly designed dwellings, crowding out the vista that formerly stretched without interruption to the distant blue of the Wicklow Hills. And the Roman triumphal arch that Lord Loftus commissioned as a grandiose gatehouse to the Castle, near a new bridge over the River Dodder, lingers in melancholy isolation, severed from its park by a housing estate, on the edge of a busy road. At least the Castle survives.

Simon Loftus is the author of The Invention of Memory: An Irish Family Scrapbook.