Linda Brunker’s female avatars affirm nature and spirit. Mark Ewart talks to the Irish sculptor as she departs California for France

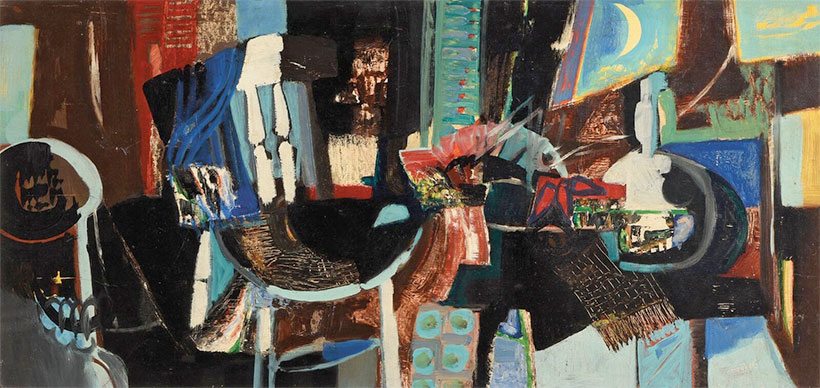

For centuries artists have striven to capture and represent the inherent sensuality and athleticism of the human figure. As a subject, it has populated a bewildering number of complex narratives and aesthetics that ruminate upon the purity or corruptibility of gods and mortals alike. And while it might be argued that the subject has lost some ground within contemporary art practice – in Irish painting at least – Expressionist artists like Patrick Graham keep the figure relevant today (in his case through the ‘visceral’ side of human psychology and identity).

In the arena of figure-based sculptural practice, Dublin-born artist Linda Brunker also immediately comes to mind. For her and many other sculptors, the human body is a device to express movement within physical or temporal boundaries; demarcating its proximity to the built or natural environment. Her impulse however is not necessarily pure formalism, as she tends to favour bronze structures built through intricate layering of modular shapes. These have a geometric purity, propagating cast patterns made from, as the artist has stated ‘a collection of elements from nature such as leaves, flowers, fruit, seeds, butterflies, feathers and birds’.1 These are ‘woven’ together to create open or melded ‘lattice’ forms that phase between solidity and transparency. Do these motifs run in concert with the human figure at the outset, or do they evolve later in the process? ‘When I work with organic motifs I don’t see them as decoration laid on top of a figure’ she clarifies, ‘these elements are the figure. They make its surface and are intrinsic to it – as blood or skin is to a human body’.2

There is deep meaning within Brunker’s work that is contiguous with the poise and grace of her figures, which are much sought after. These are mainly female figures, which at times, seem to be in a trance-like state on the cusp of reaching for the sky, as in Gaia’s Garden (2007) (Fig 7) or Voyager (2003). At other times, the figure folds into a foetal position, as in early pieces like Oak (1989) or Foliose (1990/91) (Fig 6), which listen to and merge with the earth. This is not the grittiness of the aforementioned Expressionism, rather a contemplative and intuitive idealisation of the figure. In James Lovelock’s influential book Gaia – which was surely an influence on Brunker – the author considers how the destructive forces of nationalism need to give way if there is to be ‘‚Ķan increased sense of well-being and fulfilment, in knowing ourselves to be a dynamic part of a far greater entity‚Ķ’.3 This chimes with some of the underlying messages that the sculptor is reflecting upon – and in an era of perpetuating negativity, fear and bigotry – arguably heightened to the nth degree in the digital age – maybe her work offers an escape route.

There is an intriguing duality at work when one considers the intensity of her emotional and spiritual connection to the environment

Most artists will identify with the difficulty in unearthing ideas and imagery locked away in the intellect, memory or emotions. Brunker seems to navigate her way through this by relying on her instinct or ‘sixth sense’.4 This spiritual dimension implies her work has a meditative or contemplative quality to it? ‘Yes, for me my work has a meditative quality. Much of it would be tedious or monotonous to most people, but for me it is when I am happiest and most myself!’. She continues, ‘I am interested in Metaphysics and spirituality. This is my husband’s profession and our mutual interest in these subjects brought us together’.

Breathing life and fluency into rigid materials is a challenge, but doubly so when Brunker’s themes demand lightness of form. She finds that the process of casting can be convoluted and indeed the materials are ‘cumbersome and heavy’ – but nonetheless, she still manages to capture what her mind’s eye visualises. The bronze piece Coming Round (1994) seems to register this dichotomy and her rhetorical tongue-twister – ‘how do I make a flying figure from a filigree of feathers?’ – fits perfectly (Fig 5). The timeless poise of the head proclaims Classicism – so much so that one imagines it as a magical prosthetic for The Winged Victory of Samothrace, the 2nd century bc Hellenistic masterpiece.

Even before her graduation from NCAD in 1988, the sculptor recognised the importance of making connections with institutions and organisations and getting her name out there. Of particular note was her role as a board member in the Sculptors Society of Ireland organisation. She recounts that ‘It was a busy time with the 1% per cent scheme for public art being implemented and a pro-active SSI, organising international symposiums and public art competitions’. Also during this early phase of her career, she dedicated approximately five years to organising the ‘Sculpture in Context’ series of exhibitions in Dublin. All of these experiences proved to be invaluable for understanding the commissioning process for public art and the administration of gallery exhibitions.

The improving infrastructure and support for artists at that time was important for many sculptors from across the country. The appetite for public art in Ireland was starting to take hold as economic reform – precipitated by increases in EU funding – created new opportunities for artists. Brunker was well positioned as her themes touched upon global and environmental issues, spirituality and inclusion; which perhaps fortuitously would later have currency for the soon to erupt Celtic Tiger in the mid 1990s. Wishing Hand (2001) (Fig 3), which was commissioned by the OPW for the Department of Education offices on Marlborough Street, Dublin was a case in point. The artist conceived the piece to have an interactive dimension, where a member of the public – but especially children from the neighbouring primary school – could sit into the palm of the hand and make a wish. The symbolism of the piece perhaps resonates more so today within an increasingly liberal and inclusive Ireland, than it did when it was first made.

Such important commissions and purchases from the OPW and AIB were milestones for the artist and these copper-fastened her confidence and determination in the studio. ‘I consider myself ‘lucky’ that since I started making art there has been an appreciation for what I do. These purchases and validations have helped to make it possible for me to continue to do what I do’. Her gratitude is obvious and more than sincere, but she is also quite pragmatic as she tends to look forward rather than backwards, ‘When a piece is sold I forget about it – I am focused on the next work… I just keep making what feels right to me at the time’.

The sculptor moved from Ireland to California twelve years ago and is now again going through a major uproot – this time to the south of France – where she currently in the process of setting up a family home and studio. A change of scene undoubtedly brings new influences, but tellingly, she feels that her work has not undergone significant changes with each move. The visual world energises and motivates her so that she is able to pick up where she left off – after all, there is so much to perceive and appreciate in nature. She singles out her time living at the edge of a National Forest in California, where encounters with Coyote, Rattle Snakes, Black Bear, and Mountain Lion came with the territory. ‘I loved the diverse landscape’ she asserts, which consisted of ‘deserts, mountains, forest, and ocean and I learned much about nature as I tended my small farm with goats, cows, chickens, geese and my beloved arctic wolf!’

There is an intriguing duality at work when one considers the intensity of her emotional and spiritual connection to the environment. Public art is not normally by its nature an intimate personal dialogue with oneself (unlike the artist who exhibits in a commercial gallery every other year). There does seem to be pathways for Brunker’s personal, sometimes esoteric themes to migrate into public spaces and potentially offer a conduit for city dwellers to ‘re-connect’ with nature and spirituality. Her recent public art projects in China, such as the playfully surreal and colourful Plant Head (2013) in Suzhou (Fig 4), has allowed her to explore this interface – interested as she is by the dichotomy between rural traditions and high-rise living. Chinese officials have acknowledged the way her sculptures ‘humanise’ the urban spaces, but the artist is more than happy to defer in turn to ancient Chinese philosophies and principles. ‘I feel a kinship with this culture‚Ķ their traditional ways of contemplating life and reflecting on nature strike a chord with me’.

With several large-scale public projects in development, the sculptor expects to be spending a lot of time travelling between France, China and the USA. The administration side of her work has in recent years infiltrated more and more into her time (this reached its apogee when she established Gallery 13 Irish Fine Art, in Los Angeles in 2007). In the future she hopes to get help with the administration side of things, allowing her more time for creative ends. France will offer some continuity with the haven she found in California as she has chosen to live in Occitanie – a region entrenched in traditional and rural ways of life. ‘I used to think that I knew how my life would be and what I wanted. As I get older I try not to make those assumptions but rather keep an open mind on where I will go and what I will do. I know I will make art for as long as I am physically able. It is what I was born to do’.

Mark Ewart lectures at CIT Crawford College of Art and Design. He is also an art teacher at Ashton School, a writer and artist based in Cork City.