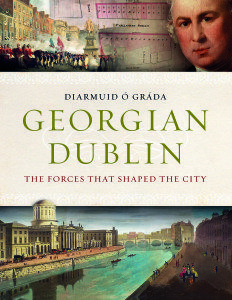

Diarmuid √ì Gráda

Cork University Press, 2015

pp 256 fully illustrated h/b

€39.00 ISBN: 978-1-782051-47-3

William Smyth

The Georgian Dublin of well-designed greens framed by architecture and elegant houses is well-documented. In this intriguing and handsomely decorated book, which focuses on the turbulent lives of ordinary people, fascinating insights are provided of a very different city. For example, in the 1760s 400 women silk-weavers were expelled from their looms by male colleagues; the first Magdalen Asylum was established in 1766; allocated their own suites, genteel patients in St Patricks Hospital (founded in 1757) brought their servants and hens with them; the latter taking over the two small yards officially designated for the sickest paupers. In 1786 there were 300 brothels with a drink license and many others besides. In an already teeming city in receipt of many impoverished rural migrants, the overall impression conveyed here is of a deeply divided and hierarchical society, where degradation, chaos, brutality, injustices, segregation and corruption prevailed. From hard-won research amongst newspapers, pamphlets and the records of the parishes of the Established Church (the latter were responsible for most aspects of 18th-century local government), √ì Gráda writes incisively: ‘Something akin to a caste system governed the city’s parks‚'(page 114); ‘As the city expanded so did the mounds of manure‚'(page 152). In early chapters, √ì Gráda illuminates the ‘push and pull‚’ forces shaping the design, social geography and ‘government‚’ of the city. Final chapters document the changing ethos and development strategies of the second half of the 18th century, especially the influential work of the Wide Streets Commission.

But the core of the book is about the attempts of diverse groups of people to make a living in a densely populated city. Middle chapters focus on crime (rampant), the failure of the legal system, levels of poverty and disease, institutional responses to deprivation and the fertile interface between criminality and immorality. The social contrasts between well-to-do well-managed parishes and poorer inner city parishes were immense and sharpened further with the exodus of the wealthy to the outer-suburbs in the later part of the century.

At this time Dublin was a violent place. Up until 1750 wrongdoers were subject to medieval sentences such as burning, scourging and the pillory; whippings reached a peak in the 1780s and of the 242 people hanged between 1780 and 1795, thieves were very much in the majority.

√ì Gráda’s account is replete with corrupt parish watchmen and police, rampaging soldiers, colliding factions and collusion between prostitutes, gamblers and criminals which at the upper end of the market overlapped with some of the ruling elite. The sequencing of the argument in some chapters is a little obscure and one greatly misses concluding chapter summaries. The final major chapter (12) on ‚’ Prostitution‚’ seems misplaced and would more fruitfully follow ‘Criminality and Immorality‚’ (chapter 8). Useful comparisons are made with other European cities; comparisons with colonial cities outside of Europe would also have been useful. Overall, this is an insightful and beautifully produced book which Cork University Press has adorned to its usual high standard.

William Smyth is joint editor of the Atlas of the Great Irish Famine (CUP, 2012) and author of the prize-winning Maps Landscapes and Memory (CUP, 2006).