Morna O’Neill

Morna O’Neill

Yale University Press, 2018

pp 274 fully illustrated h/b

€44.00/ £40.00 ISBN 978-0300-236583

Reviewed by Philip McEvansoneya

Morna O’Neill’s informative and well-presented book concentrates on Hugh Lane as a dealer and as the founder or benefactor of galleries not only in Dublin but also in South Africa. Although Lane’s well-known involvement with modern continental art is examined, the main emphasis is on British and Old Master works. The running theme of the book is to consider the tension between the private commerce of the dealer and the public role of the cultural philanthropist and arbiter of taste. O’Neill’s underlying argument is that Lane sought to distance himself from the market and instead to perform the role of the gentlemanly connoisseur who occasionally sold from his collection to the right person when needs must. Yet it was dealing that provided Lane with the wherewithal to become a philanthropist.

The book consists of four main chapters. The first introduces the concept of decoration in relation to Lindsey House, the premises in London where, from 1909, Lane both lived and displayed his principal stock. There, he fabricated a setting intended to suggest an historic aristocratic mansion in which paintings along with a variety of objects including furniture, porcelain and sculpture were arranged as a decorative ensemble.

O’Neill’s underlying argument is that Lane sought to distance himself from the market and instead to perform the role of the gentlemanly connoisseur who occasionally sold from his collection

Decoration is further explored in the second chapter in relation to the Municipal Gallery of Modern Art as it was originally installed in Harcourt Street in Dublin. Lane’s ambitions to found an ideal gallery as a gesamtkunstwerk combining elegant architecture, interior decor including murals, and a meritorious collection came to nothing with the failure of his plans for a new building either in St Stephen’s Green or spanning the Liffey on the site of the Ha’penny Bridge.

Lane’s role in gathering a collection of Modern British and continental art for Johannesburg and another of 17th-century Dutch works for Cape Town is then set out, and the preference shown for ‘direct’ works of art that appealed to untutored eyes is made clear. The two locally sponsored collections acknowledged Britain as the controlling imperial power on the one hand, and the Dutch origins of many settlers on the other. Handling the political context lightly, O’Neill sets this outcome in the context of the ‘closer union’ policy that followed the Second South African War.

The fourth part positions Lane in the transatlantic art market and assesses his failed plans to take advantage of the very wealthy Americans whose collecting was so profitable to European dealers from the 1880s onwards. Lane’s dealings in Old Masters with Henry Frick and others, although ultimately profitable, are shown to have been very circuitous, relying on intermediaries. As for modern work, Lane could not keep up with its rapid evolution, unlike his acquaintance the Irish-American collector, John Quinn, who is presented as a point of comparison. What seemed avant-garde to Lane in 1904 was old hat by 1912. When Quinn was filling his Central Park apartment with works by Picasso and others, Lane was telling an American friend that ‘I do not like syphilis in my parlour’.

Philip McEvansoneya is a lecturer in the History of Painting at the Department of the History of Art and Architecture at Trinity College Dublin.

Comhghall Casey is a keeper of ordinary things made extraordinary through his art, writes Isabella Evangelisti ahead of his exhibition at Solomon Fine Art this autumn

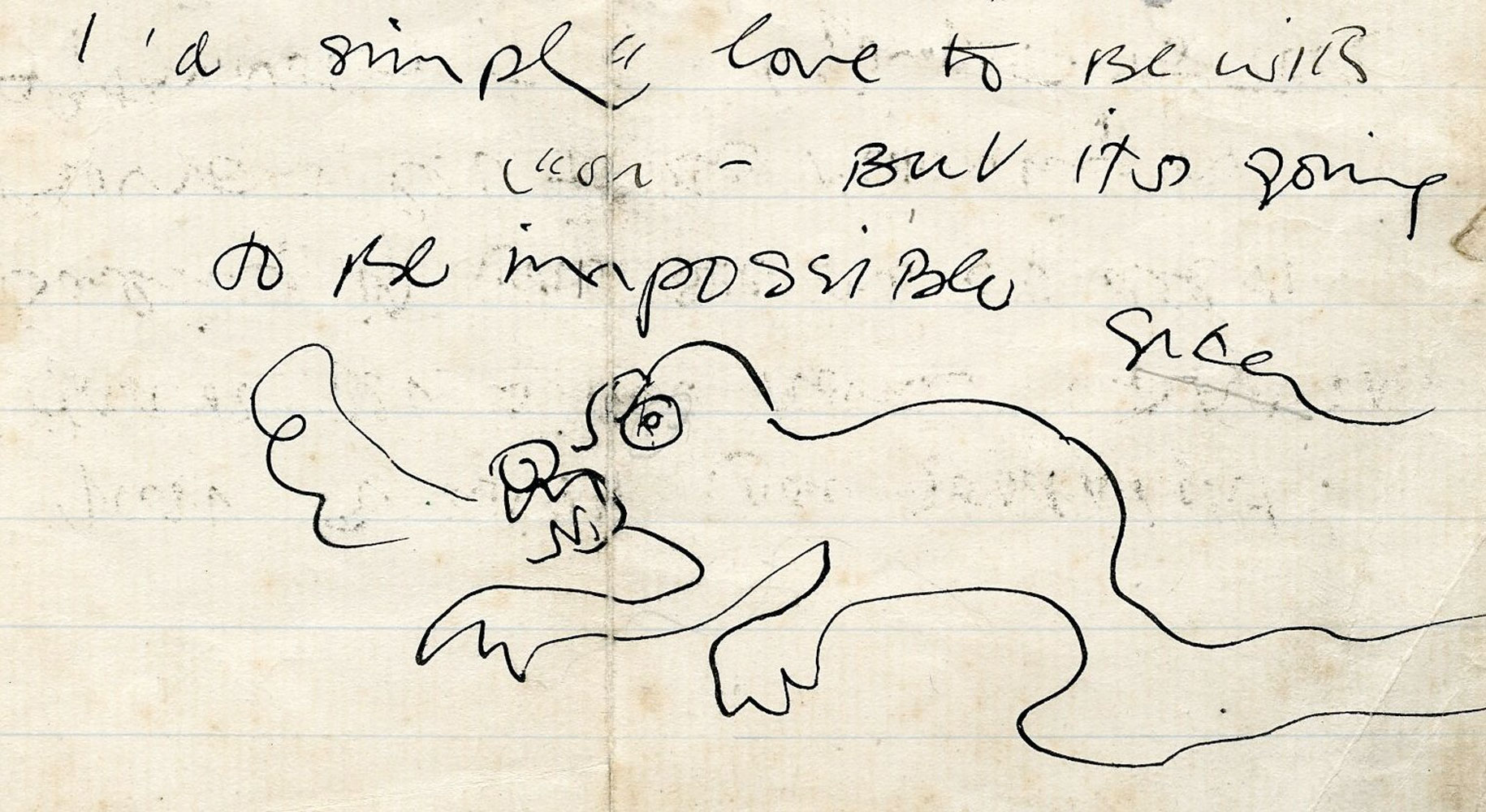

Christian Dupont reflects on the personal and political desires conveyed in two cartoons by Grace Gifford Plunkett

Recently elected ARHA Sinéad Ní Mhaonaigh is proof that the outward appearance of Academicians may change but the concern with discipline remains constant, Niamh NicGhabhann reports