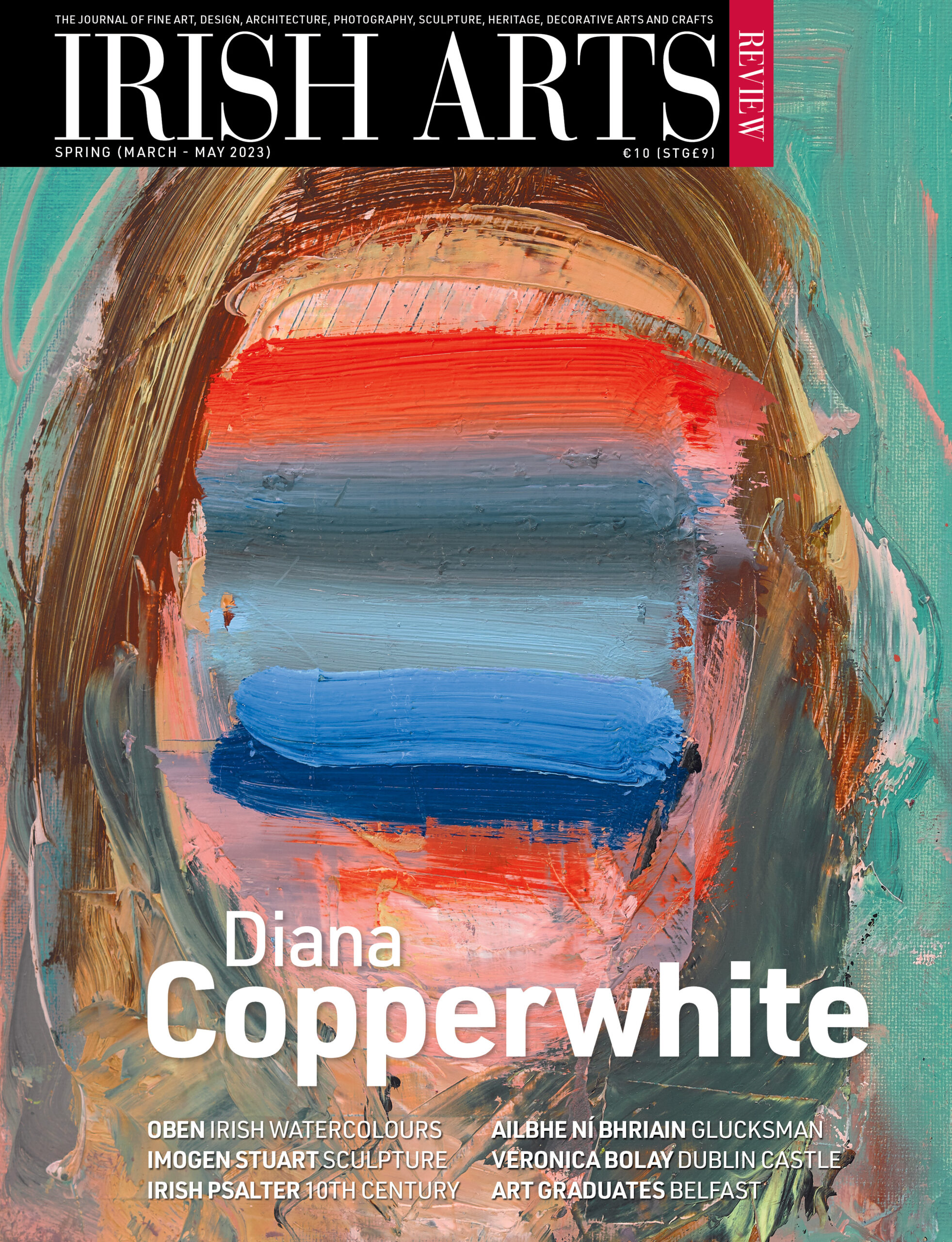

Paula Murphy celebrates the work of Imogen Stuart over the course of her six-decade career

When members of the public in Ireland are questioned as to a favourite piece of sculpture, they will often mention works by Imogen Stuart – her Fiddler of Dooney and Children (1964–5) in the Stillorgan Shopping Centre in Dublin (Fig 5), her Group of Children (1969) in Tyrrellspass, Co Westmeath, her ‘very spectacular’ relief of St Michael and the Dragon (1973) in St Michael’s Church, Dún Laoghaire (1), her Monument to Pope John Paul II (1986) in Maynooth College and The Flame of Human Dignity (2005) in the grounds of the Centre Culturel Irlandais in Paris, to name but a few.

Vast numbers of students at University College Dublin, particularly those studying the humanities, had the opportunity to engage with her Pangur Bán (1976), which was once strategically positioned in the Newman Building on the Belfield campus. Sadly for the students, this multi-part sculpture, which is based on an early Irish poem, and with which Stuart has a special relationship, was subsequently moved to Áras an Uachtaráin. Students at Mary Immaculate College (MIC) in Limerick have been more fortunate in their engagement with her work. MIC and Stuart have a long-standing association which stretches from the early years of her career in Ireland in the 1950s to a recent exhibition of her work in their newly refurbished chapel curated by Naomi O’Nolan. The Stuart works owned by the college which were included in the temporary exhibition are more usually displayed across the campus for the staff and students. Titled ‘Imogen Stuart – In Her Hands’, the exhibition largely comprised works drawn from the MIC collection and from the sculptor’s own. The Gothic Revival chapel on MIC’s John Henry Newman campus served as a perfect venue for the mostly religious work by Stuart that formed its inaugural exhibition. Like much of Stuart’s oeuvre, the exhibits were intimate in scale.

The Sisters of Mercy at MIC have had an ongoing role in the progress of Stuart’s career in religious sculpture, most particularly at its outset. Most of the pieces in their collection were commissioned directly from the sculptor. The first group, in 1958, were three life-size statues, St Brigid, St Colmcille and Christ Teaching, all wood carvings. The simplicity of form evident in these works has remained a hallmark of Stuart’s output. An earlier work in the collection came by way of a donation. GardeRobe (1948), a commissioned work, is not what we think of as a wardrobe, but more a dedicated open wood form for hanging coats. Beautifully crafted in oak, GardeRobe is exquisitely detailed with animals and plants. Further works by Stuart were added to the MIC collection in subsequent decades, including, in 2005, The Psalm No 8, which takes the form of a ladder (Indian paper and wood). Rising toward the heavens, the ladder has the text of the psalm written across each of its steps, showing yet another of Stuart’s abilities – her skill in lettering. All of the works in the collection manifest Stuart’s characteristic high finish.

Stuart’s work at MIC is not simply used to enliven the architecture, but is actively employed in the Stuart’s work at MIC is not simply used to enliven the architecture, but is actively employed in the teaching programme. The different sculptures serve as a resource for discussion around aesthetics, subject matter, materials and sculpture techniques. They are also used by those engaged in German Studies in the college, notably in their exploration of Irish-German relations and German styles in sculpture in the modern period.(2) A group of students taking the module ‘Irish-German Relations since the 18th Century’ in 2011 were fortunate to have Stuart discuss her life and work with them.(3) She had much to impart.

Born in Berlin in 1927, Imogen Werner was aged five when Hitler came to power. She grew up in wartime Germany. She was familiar with art from an early age – her father, Bruno Werner, was the arts editor of a leading daily newspaper, the Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung. He encouraged her interest in art and was instrumental in gaining her access to study with Otto Hitzberger (1878–1964). Hitzberger taught wood and stone sculpture and, although included in the Degenerate Art (Entartete Kunst) exhibition in 1937 – at the time a stigma, but now perhaps an experience to be worn with pride – he would subsequently receive many honours and awards. Stuart was to learn much in Hitzberger’s studio, but, perhaps even more importantly for her future life and career, she was also to meet her husband there. Irish sculptor Ian Stuart (1926–2013), grandson of revolutionary and actress Maud Gonne and the son of author Francis Stuart, also came to study with Hitzberger at the time. Stuart and Werner moved to Ireland in 1949 and married in 1951. They had shared sculptural interests in the early years of their respective careers, notably wood-carving and religious work, and often worked together. However, their styles diverged as their work and lives took different paths, and they separated in 1972. In an interview in 1973, discussing some of her recent work, Imogen Stuart, perhaps noting intentionally the contrast between her work and that of her former husband, commented, ‘I don’t think I could work abstract at all’ (4). By this date Ian Stuart had had considerable success with large-scale abstract sculptures.

Imogen Stuart was not the only foreign artist to join and make an impact on the Irish sculpture scene in the mid-20th century, although she arrived first. Not long after Stuart, two other female practitioners came to Ireland: Gerda Frömel (1931–1975, born in Schönberg, in what was then Czechoslovakia, arrived in 1956; Alexandra Wejchert (1921–1995), born in Kraków, Poland, arrived in 1965. All three became major players in sculpture in Ireland, notably public sculpture, and contributed significantly to the development of that art form. While Stuart’s public work remained figurative and, as a result, more accessible to the public, Frömel’s and Wejchert’s public work was largely abstract. All three were adopted by their new country and are incorporated into the history of Irish art with no more than a passing reference to their place of birth.

Stuart’s affection for Ireland was immediate. ‘As soon as I arrived, I knew this was my country. I was totally taken over by Irish art: the landscape, the ruins, the history of the saints and scholars.’(5) The imagery in her work is often influenced by early Irish art and her strong association with wood, identifying it as her preferred material, may have some connection with her early years living in Glendalough. ‘I like wood best,’ said Imogen Stuart in 1973, by which time she was living in Sandycove (6). ‘I love teak and other hardwoods… if you understand them, they are very willing. (7)’ ‘Now stone, I never liked working in stone because it’s cold and has a hard sound, that’s why I’m mad about wood. (8)’ If, in 1973, Stuart indicated her dislike of stone, this rejection would not be sustained. The recent MIC exhibition included a range of work in different stones: granite, Caen stone, Carrara marble, Portland stone and Portuguese limestone. And if the stones employed were varied, so too were the wood types: pearwood, oak, elm, Spanish chestnut, pitch pine, cedarwood, teak, mahogany.

This concentration on varieties of wood and stone ignores the fact that Stuart also works in bronze, not only for her public sculpture, but also for smaller works. In the last two years she has cast many small bronze pieces (Fig 9), some of which hover between relief and three-dimensional forms. Mostly religious, they represent: A Scholar Writing; St Francis and the wolf of Gubbio; St Killian and Monks Set Sail for Würzburg; Madonna and Child; Madonna, Jesus and a Human Child; In Principio; Madonna and Child.

Stuart has been in receipt of commissions throughout her career. The continuous demand for her work has meant she has had less involvement in temporary exhibitions and less reason to participate in them – although she regularly sends work to the annual RHA exhibition. Often making reference in interviews to the importance of commissions, she has revealed the pleasure she takes in working to the requirements of each commission – ‘every time it was a new challenge with the same five limitations: subject, size, material, place, budget… I believe confinement and restriction are really good for creativity’ (9). Stuart is unusual in this. Sculptors are usually more inclined to bemoan such restrictions – in particular, to find the budget inadequate and the time allocated insufficient.

Appointed Professor of Sculpture at the RHA in 2000, Imogen Stuart has received much recognition in the course of her long career, winning awards and receiving honorary doctorates. She was elected a member of Aosdána in 1981 and elevated to Saoi in 2015. She is represented in the National Self-Portrait Collection at the University of Limerick by the first 3D portrait to enter the collection. She makes use of the silhouette form in her Self Portrait (Fig 3), presenting both of her profiles, rather than just one, and appearing more 1920s than 1980s, perhaps because of her trademark haircut.

While Stuart has done portrait work, notably a bust of actor Barry McGovern (1992, bronze), she is more readily associated with other subject matter, returning again and again, for example, to the theme of the Madonna/mother and child, to the image of the crucifixion and to the Stations of the Cross. These last have been commissioned for many locations, the earliest of which in Ireland were for the Curragh Camp Church in Kildare (1957, teak); Muckross, Killarney, Co Kerry (1958, oak); Milford, Co Donegal (1959, polychrome); Lettermore, Co Galway (1959, teak). Her set of Stations in Ballintubber Abbey, Co Mayo (1972, polychrome terracotta) was illustrated in newspapers at the time of their installation and is perhaps her best known. The forms are medieval in style and compact in both size and compositional arrangement. The use of colour on the skilfully crafted forms enables the narrative to be easily communicated. Discussing a later set of Stations of the Cross, Stuart stated that her ‘purpose is to help the praying person… meditate on the mysteries presented’ (11). And while she claims ‘not [to] belong to any specific movement’, she nonetheless acknowledges that her work has been greatly influenced by Romanesque and Expressionist styles’ – styles that merge in the primitivism in her work.

Her association with religious sculpture has caused her a measure of discomfort during her career, engendering occasional negative comment from some among her peers. But Stuart has pointed out that such commissions meant that she was never without work, and particularly ‘at a time when most sculptors in Ireland did not have things easy’(12). And, in spite of the extent of her religious work, Stuart reveals her associated humorous side in her etching Visual Resumé (also referred to as Visual CV, 1997), which is a compilation of tiny sketches of many of her works with comments surrounding them. She claims here, mischievously, not to have cared when someone was rude about the form of one of her Madonna and Child sculptures, which in turn seems related to the rejection of one of her works by an American Mercy nun for their convent on Baggot Street, because ‘it was too much like a phallus’. She also notes on this etching, alongside a sketch of a naked man and woman, that ‘a photograph of this couple was taken out of my album when I showed my work to priests’.(13)

MIC awarded Stuart their McAuley Medal in 2010, an award that was initiated to recognise those who have impacted society by way of their vision and exceptional personal commitment to the good of the wider community. Speaking at the opening of the MIC exhibition in December 2022, President Michael D Higgins underlined the way in which Stuart, through her work, enriches the lives of many, identifying the importance to her of the work being accessible and available, democratic and dissociated from class and privilege. Her Fiddler of Dooney and Children (beaten copper), exemplifies the President’s choice of words. When Stuart’s work appeared in the Stillorgan Shopping Centre in 1965, everything about it was new – the imagery, the scale, the location. The public sculpture already in place in the city was largely commemorative, lofty and mostly ignored. Here was a work that people could see and touch – in which children could participate – depicting a subject to which people could relate. It is a work with which people became very familiar, a work that is accessible, available and democratic.

Paula Murphy is Professor Emeritus, School of Art History and Cultural Policy, UCD.

1 Interview with H Cooke, Irish Times, 1 May 1973

2 Imogen Stuart: In Her Hands, exhibition catalogue, Limerick, Mary Immaculate College, 2022 p7

3 Limerick Leader, 2 March 2011

4 Cooke op cit

5 Interview with D Scally, Irish Times, 22 August 2009

6 Cooke op cit

7 Interview with R Boland, Irish Times, 2 October 2021

8 Cooke op cit

9 Scally op cit

10 I Stuart in B Fallon, Imogen Stuart, Sculptor, Dublin, Four Courts Press, 2002 p139

11 Ibid p137

12 Ibid p28

13 Visual Resumé, 1997, artist’s collection

[See also B Fallon, Irish Arts Review, vol. 23 no.1 (2006) pp80–5]

Isabella Evangelisti visits the MAC in Belfast, where the work of selected painting graduates from Belfast School of Art is on show