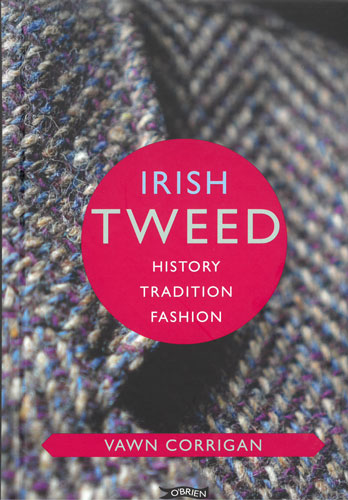

VAWN CORRIGAN

VAWN CORRIGAN

O’Brien Press, 2020

pp 192 fully illustrated h/b

€12.99 ISBN: 978-1-78849-021-4

Deirdre McQuillan

One of Ireland’s great lost textile opportunities was not protecting Donegal tweed with a trademark. The famous Harris tweed from Scotland has been safeguarded in this way since 1910, and its industry and workforce – 400 islanders – can rely on it for their livelihoods. Donegal tweed, however, one of this country’s most famous heritage textiles, is now a generic term, like that of the Aran sweater, describing tweeds with flecks of colour even if made in China or elsewhere.

In Vawn Corrigan’s popular new book on Irish tweed, which covers its history and legacy, she cites Lorna Macauley, chief of the Harris Tweed Authority, saying that the Irish government ‚Äúhaven’t yet taken the steps of protection that we have; we get enormous support to protect Harris Tweed‚Äù. To see an Irish craft so celebrated internationally but neglected at home says a lot about cavalier attitudes to this country’s native skills and traditions.

Fabric and cloth shaped our history and finances. Most of the book tells the story of tweed, how it is made, the various patterns and dyes used, and the skills required for its production. There are descriptions of the earliest accounts of common outfits worn “for centuries” in Ireland Рthe “shaggy brat” (a woollen cloak exported all over Europe) and the leine (a long, gathered shirt).

Irish woollen textiles were highly prized in the 16th century: one record from Bristol shows that, in the three years from 1557 to 1560, some 26,550 yards of Irish frieze used for capes were imported from Ireland. But, by 1673, the thriving industry and export trade was crushed by the British with a ban on Irish wool products to protect English-based wool manufacturers. Although repealed in 1779, the large-scale Irish woollen industry, developed over five centuries, was destroyed.

A popular rather than an exhaustive history, the book has interesting stories, the best told by the weavers themselves, which might have been worth expanding

Tweed’s resurgence and decline in later years is also outlined from the famine to the present day. A popular rather than an exhaustive history, the book has interesting stories, the best told by the weavers themselves, which might have been worth expanding. There are, however, aspects of Irish tweed that are overlooked; no mention is made of Irish sheep from whose fleece tweed was made (an important consideration of its agricultural origins), nor the weavers currently educating a new generation.

As for fashion, Pat Crowley (not Crawley) was one of a group of designers attempting to keep its fashion profile high in upmarket stores in America from the 1960s. Their attempts, however, ultimately failed, as did those of many other Irish companies faced with imports from low-cost countries. “Very little effort was made to protect them,” says Corrigan.

Today there are encouraging signs of a revival, with designers and consumers rejecting fast fashion and recognising sustainability and the importance of fostering heritage textiles, so Irish tweed is once again in the news, making this a timely publication.

Deirdre McQuillan is fashion editor of the Irish Times.

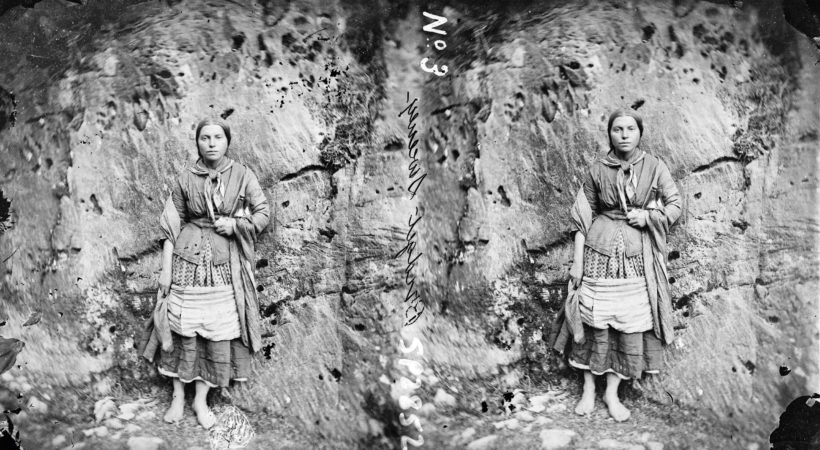

The collection of 19th century stereo negatives of the Gap Girls of Dunloe in Kerry comprise a rare and unique body of work, writes Julian Campbell