Nigel Everett recounts how John Annan Bryce and his architect Harold Peto transformed Garinish Island into one of the most important gardens in Europe

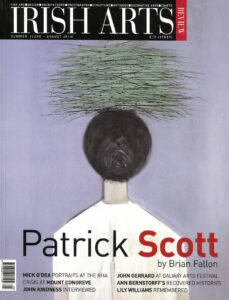

Garinish Island comprising thirty-seven well-sheltered and spectacularly panoramic acres in Glengarriff Bay, West Cork, first acquired national significance as part of the British government’s defences against Napoleon. A fort, barracks, and Martello Tower were built by 1805 but promptly rendered obsolete following Nelson’s victory at Trafalgar. The Cork antiquarian John Windele, writing in 1837, described the ruined fortifications of Garinish as its principal feature, ‘not unpicturesque’ and crowning a ‘rocky summit’. By this time, the peace of Garinish faced a new threat; the projected railway from Berehaven to Cork would leap across the island, newly connected to the mainland by two viaducts of seven and fourteen arches.

Nothing came of the scheme, and the peace of Garinish remained largely undisturbed until 1910, when it was acquired by John Annan Bryce (1841-1923), MP for Inverness Burghs. Born in Belfast of Scottish stock, and educated at Glasgow and Oxford, Bryce had been active in the commerce and administration of Burma and India; he participated in various expeditions, including plant-hunting, in Burma and Upper Siam, duly reported to the Royal Geographical Society. Together with his wife Violet – born in Mauritius to the evocatively named Captain Champagné L’Estrange, an RM in Co Down – Bryce had been seeking a horticulturally and picturesquely rewarding demesne for some years, making their principal base at Glengarriff Castle.

Writing to the London Times in the autumn of 1920, Bryce noted that BRITISH government forces had largely been responsible for the ‘molestation’ of loyalists

The transformation of Garinish was mainly entrusted to Harold Peto (1844-1933), an English gentleman-architect long known to the Bryces. In 1905, Bryce and Peto undertook a tour of County Cork gardens, notably Fota. Work began in 1911, employing 100 men, with an emphasis on the planting of shelter belts – Scots, Monterey, Austrian, Mountain, and Corsican pine, birch, and Monterey cypress – and the enrichment of terrain largely consisting of rock and peaty turf. In at least one of its manifestations, the Bryces’ new mansion – designed in collaboration with the Belfast architects Young and Mackenzie – was clearly intended to be as striking as nearby Bantry House and Dunboy Castle. A seven-storey affair, standing on Windele’s ‘rocky summit’, it mixed elements of Romanesque, Italian Renaissance, and Celtic Baronial. The Martello Tower featured as a garden room, music room, and ‘Mrs. Bryce’s room’. The adjoining gardens were to reflect the Medici villas around Florence, with loggias, an ambulatory, arcades, balustrades, terraces, formal beds, stone staircases and balconies. The air of connoisseurship was to be confirmed by the use of a wide array of artefacts – they included statues, vases, fountains, iron gates, a Byzantine tomb and a sculpted stone relief described as the ‘Camerini lion’ – collected by Peto and Bryce on their various travels.

To the west of the mansion Peto planned a rectangular ‘privy garden’, enclosed on three sides by yew hedging, and at its centre an octagonal pool with a fountain. A series of formal gardens was to be placed on a west-east axis, with an amphitheatre and sunken garden leading to an ‘English lawn’ – partly available for tennis and croquet – and a walled kitchen garden. This would contain three vineries – ‘Late’, ‘Early’, and ‘Muscats’ – a Flower House, houses for early and late peaches, two orchid houses, and two forcing houses. The north-eastern corner of the island was to contain a rose garden – an elaborate parterre intersected by a pergola – and a crab apple orchard. Another west-east axis would feature a temple leading via a long stone staircase to woodland glades and a grass allée opening onto the broad sheltered expanse of an area known as the Happy Valley. This axis would end with steps up to the mansion; along its course there were to be separate areas devoted to acers, heathers, azaleas, lavenders, andromedas (pieris), and alpines.

The cosmopolitan credentials of Garinish would be underlined by the use, in addition to local stone and green Connemara marble, of Bath stone, Carrara marble, and yellow-veined marble from Scyros. There was also to be an important influence from Japan. Visiting in 1898, Peto had admired the subtle incorporation of elaborate gardens into dramatic landscapes featuring great stretches of water, ‘gigantic rocks’, and ‘steeply wooded hills’. Amongst trees and shrubs, Peto was especially struck by ‘great pythons’ of wisteria, the ‘solemn gloom’ of cryptomerias, the ‘exquisite tints’ of maples, and the picturesque character of ‘wind-blown pines’. Peto also relished the particular Japanese enthusiasm for delicate combinations of pink, white, and red, notably in roses, deciduous magnolias, ‘clouds’ of cherry and peach blossom, and juxtapositions of the white-flowered Japanese sacred bamboo – Nandina domestica – with the rose-coloured azalea, R. indicum. Above all, perhaps, Peto admired thickets of ‘exquisite’ pieris, with their thousands of ‘pearly white tassels of bloom’ and ‘young shoots a tender copper red’.

Japanese gardens were equally remarkable for their capacity to discover ‘as much beauty in a bit of picturesque or lichened stone, as in any choice shrub’. Peto was keenly opposed to the ‘too catholic desire’ amongst westerners to favour polychromatic bedding schemes, herbaceous borders, and shrubberies.

The relevance of Mercury to the climate of Garinish and the wealth of its owner was clear enough. It is underpinned by a further allusion – to the Villa Medici, Rome

Bryce’s plans – most especially the mansion – were largely curtailed by the Great War, financial difficulties – in large part a result of his over-investment in Russia – and the disruptions attending Irish independence. The Bryces felt much more perturbed by the RIC and the Black and Tans than the IRA. Writing to the London Times in the autumn of 1920, Bryce noted that British government forces had largely been responsible for the ‘molestation’ of loyalists. The victims included the late Egerton Leigh White of Bantry House and Mrs. Bryce – a cousin, incidentally, of Countess Markiewicz – recently arrested at Holyhead and subjected to ‘ill usage’ for carrying letters deemed to contain ‘gross libels’ on the RIC.

Bryce died in 1923; economic imperatives led his son, Roland, to consider the partly-completed gardens as a commercial proposition, open to the public from 1925, and managed between 1928 and 1971 by a Scottish gardener, Murdo Mackenzie, whose income depended, to a growing extent, on visitor receipts. Visiting in 1943, Eamon de Valera was ‘tempted to envy you down there in your lovely surroundings’, a compliment which reinforced Bryce’s desire to bequeath Garinish (together with three Turner watercolours) to the Irish State. With Bryce’s death in 1953, government officials contemplated a ‘white elephant’ – the Bryce estate insolvent and the seven Garinish gardeners unpaid. The bequest was nonetheless accepted, and Garinish placed in the care of the OPW.

Three major elements survive from Peto’s original conception of Garinish. The Italian Garden, derived from his ‘privy’ and sunken gardens, is modelled on Roman maritime gardens, with a pavilion overlooking the sea, a rectangular pond, and a covered gallery, or cryptoportico, built of Bath stone and described as the Casita, or tea house; it is covered with wisteria (Figs 6&7). At the centre of the pond is a copy of Giambologna’s Mercury (Fig 1). The god, born on the pine-clad hills of Sparta, was ‘shepherd of the clouds’ – engaged in a constant battle of wits with the sun god Apollo – as well as an important figure in the development of art and commerce. The relevance of Mercury to the climate of Garinish and the wealth of its owner was clear enough. It is underpinned by a further allusion – to the Villa Medici, Rome, where Mercury sits atop a fountain in a garden fronted by a Palladian loggia guarded by stone lions and offering views of Rome framed by pine, holm oak and cypress. At Garinish, a Palladian pavilion, known as the ‘Medici Pavilion’, is surveyed on the opposite side of the pond by two stone lions. Pines and Italian cypress are amongst the many trees and shrubs framing a landscape of coves, promontories, and inlets yielding to the sea and dramatic vistas over the Caha Mountains.

The Italian Garden displays Japanese elements in the form of the roof-lines and, around the pool, the marking of the points of the compass by bonsai trees; one, a larch apparently around 320 years old, is contained in a Roman marble vase.

Adjacent plantings included Nandina domestica, the red-flowered Leptospermum scoparium and Clematis durandii, the purple abutilon ‘Ashford Red’, the scarlet and gold Callistemon rigidus, the pink, and exquisitely scented, rhododendron ‘Lady Alice Fitzwilliam’, and the yellow-flowered Vestia foetida. Nearby, the Cedar Bed includes the shrubs Leucothoe fontanesiana offering white flowers yielding to beetroot, and the white Clethra arborea. The Bog Bed has an ample display of Pieris formosa, var. forrestii. The Kitchen Garden has walls of stone and brick, massively buttressed, an Italian baroque entrance, scattered stone artefacts, a campanile in Romanesque style, and an elegant garden house modelled on a Georgian feature at Harold Peto’s Iford Manor, Wiltshire. Much of the grid pattern of the original fruit and vegetable garden is now occupied by herbaceous borders, nursery beds, and mixed shrubberies. A double herbaceous border in Robinsonian style – complete with delphiniums, phlox and asters – runs the whole way down the centre. Featured roses in the garden include the rugosa ‘Roseraie de l’Hay’, with purple red buds, and various hybrid musks, including ‘Penelope’ and ‘Felicia’. At one end of the Happy Valley is the Martello Tower, approached via plantings of the orange scarlet-flowered Embothrium coccineum var. longifolium, the rose crimson Rhododendron callimorphum, and the white Lyonothamnus floribundus var. asplenifolius. At the other end is the Greek Temple, a hexagonal belvedere, or Japanese ‘open gazebo’, constituting a roofless version of the temple at the Vale of Tempe, Tivoli. Accompanied by a double avenue of Italian cypress, the temple frames impressive views of the Caha Mountains. Closely-mown grass cuts through a mass planting of exotics, at its centre a lily pond planted with the elegant Australian pine Dacrydium franklinii, various eucryphias, and Rhododendron yakushimanum, with shell-pink buds opening to white. An area known as the Jungle allows a wide variety of rhododendrons – including arboreum, racemosum, and ‘Lady Rosebery’ – to flourish amidst woodland.

In reviewing the beauties of the Happy Valley, external and internal, one may be reminded of Dr Johnson’s definition – in Rasselas (1759) of such a place as one in which ‘all the diversities of the world were brought together, the blessings of nature were collected, and its evils extracted and excluded’.

It is planned that the Bryce House and exhibition will open to visitors in 2015.

Nigel Everett is a landscape historian and the author of Wild Gardens: The Lost Demesnes (2000).

From the IAR Archive

First published in the Irish Arts Review Vol 30, No 2, Year 2013