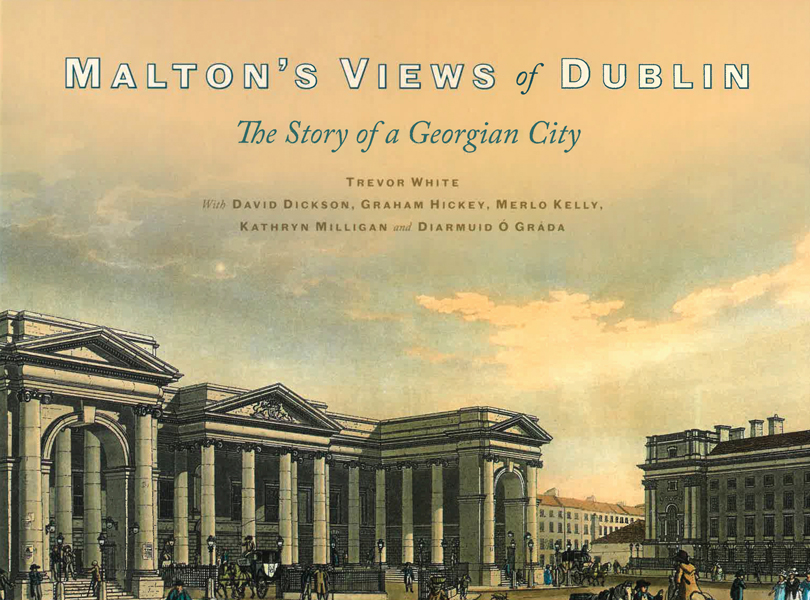

Trevor White and Djinn Von Noorden [Eds]

The Little Museum of Dublin, Martello Publishing, 2021

pp 104 fully illustrated hb

€29.95 ISBN 978-1-99989-684-3

Angela Griffith

The Little Museum of Dublin’s handsomely produced hardback volume Malton’s Views of Dublin: The Story of a Georgian City provides readers with a welcome opportunity to revisit, re-evaluate, and reappreciate James Malton’s contemporaneous hand-coloured engravings of late-18th-century Dublin. The museum’s director, Trevor White, provides a lively commentary on each of Malton’s twenty-five views of Ireland’s capital. Essays by leading voices in Irish historical and cultural studies position the images within their social, political and cultural contexts.

Malton’s work celebrates the planning achievements of Dublin’s Wide Streets Commission and the city’s grand public and private buildings – which rivalled those of the empire’s capital, London – from the imposing monumentality of the Royal Exchange to the immense imperialism of the Custom House. However, as Diarmuid √ì Gráda’s uncompromising counter-narrative illustrates, the grandeur of Dublin’s urban improvements masked the harsh reality of lower-class lives. David Dickson expertly summarises Dublin’s political and economic landscape in the late 1700s. Using evidence provided by Malton, Merlo Kelly outlines how the city was constantly modernising and adapting to serve the needs of its ruling and middle classes. Through skilful visual analysis, Kathryn Milligan demonstrates how Malton’s detailed description of a merchant’s window display reflected how Dublin’s elite saw themselves: fashionable, progressive and fitting beneficiaries of the empire.

Many scholars, including contributors to this volume, acknowledge that artistic licence was taken in order to appeal to the values and ambitions of his upper-class market.

While Malton, in his preface to the original edition, claimed that his engravings represented a ‘perfect as possible semblance‚’, many scholars, including contributors to this volume, acknowledge that artistic licence was taken in order to appeal to the values and ambitions of his upper-class market. Malton’s streets are sanitised, the detritus of urban living removed. They are depopulated, especially of the poor. Architectural features are enhanced, distorted or reduced; some buildings are presented as designed rather than as executed. For all of that, Malton’s prints are a treasure trove for the architectural historian, as Graham Hickey’s essay explores.

While created for a general audience, there is an inconsistency of tone across the book. The language used in the commentaries is at times intemperate and incongruent with the scholarly essays within. The use of local parlance is perhaps confusing for the uninitiated. There is a notable error that suggests Robert Emmet died before the Act of Union in 1801. However, the volume is mindful of its readers, aiding their travels through 1790s Dublin with annotated maps and keys to panoramic prints. The processes used by Malton, etching and aquatint, and the subsequent addition of colour by hand, are clearly explained.

This book reminds us of the ambitions and achievements of Ireland’s capital as the Industrial Age was building a head of steam and the world was becoming increasingly global. Yet, despite appearances, readers are also reminded that the 1790s was a time of uncertainty. Malton’s Views of Dublin: The Story of a Georgian City celebrates the images as historical documents, as social commentaries (on the visible and the absent) and for their unquestionable aesthetic appeal.

Angela Griffith is Assistant Professor in the Department of History of Art and Architecture, Trinity College, Dublin.

Stephanie McBride explores Deirdre Brennan’s photographic response to James Joyce’s Ulysses