Claire Breay & Joanna Story [Eds]

Claire Breay & Joanna Story [Eds]

Four Courts Press, 2021

pp 256 fully illustrated hb

€58.50 ISBN 978-1-84682-866-9

Roger Stalley

Three years have now gone by since the spectacular exhibition ‘Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms: Art, Word, War‚’ was held in the British Library. Covering six centuries of English history, it brought together under one roof almost all the most famous books of the era. Among the highlights was the Lindisfarne Gospels, along with many other highly decorated gospel books, including the Book of Durrow. The ultimate ‘show-stopper‚’, however, was the Codex Amiatinus, a gargantuan copy of the Bible, the size of a large suitcase, which was made in Northumbria shortly before ad 716, when it was carried to Rome as a present for the pope. It eventually ended up in Florence. The exhibition marked the first time it had returned to England after a lapse of 1,300 years.

The exhibition was accompanied by a conference, the proceedings of which have been published in a handsome volume that includes fourteen specialised essays, most of which focus on individual manuscripts, dealing with such matters as palaeography, textual content, provenance and the European context. It is well known that books were highly mobile and an essay by Francesca Tinti provides a fascinating insight into the way bishops and clerics travelled with their books, the latter packed away in chests along with their vestments.

It is well known that books were highly mobile and an essay by Francesca Tinti provides a fascinating insight into the way bishops and clerics travelled with their books, the latter packed away in chests along with their vestments.

Two of the essays have special relevance to Ireland. One is a breathtaking study by Dáibhí √ì Cróinín, who analyses a fragmentary manuscript (A II.10) in Durham Cathedral library. The surviving leaves come from what was once an ornate gospel book, the earliest of a series of decorated manuscripts that culminated with the Book of Kells. Here for the first time we find an elaborate coloured initial, along with a page decorated with exquisite interlaced patterns. The book originally belonged to the monastery at Lindisfarne, though that does not mean it was made there. √ì Cróinín concludes that it was written (and presumably decorated) by an Irish scribe, having detected numerous cases where the spelling was altered as if the scribe was pronouncing the words in Irish – a case of forensic scholarship at its best. Of course, scribes, like their patrons, moved around, so this tells us little about where the book was made. √ì Cróinín favours Iona and makes the intriguing suggestion that it was presented to Lindisfarne soon after its foundation in 635. If so, that would mean it was the precursor of the far more sumptuous Lindisfarne Gospels.

In several cases authors pay tribute to digital imaging, which is transforming the process of research by providing direct access to delicate material. Moreover, as Bernard Meehan explains in his essay, multispectral imaging can reveal much that is invisible to the naked eye. One hopes that before long such techniques will be applied to the Book of Kells, a process that will surely unlock some of that book’s many mysteries.

Roger Stalley is a fellow emeritus of Trinity College, Dublin, where he was Professor of History of Art.

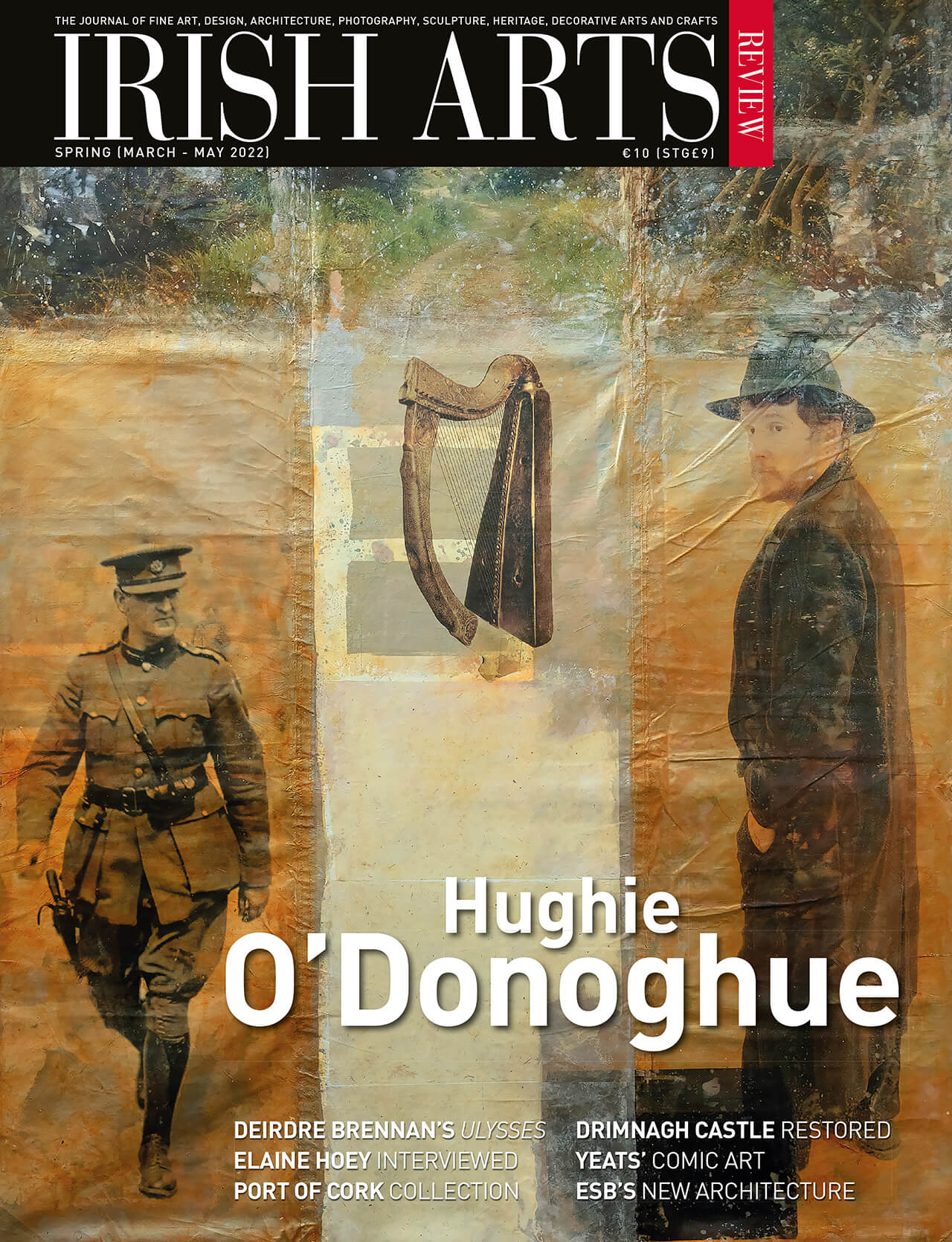

Stephanie McBride explores Deirdre Brennan’s photographic response to James Joyce’s Ulysses