John P O’Sullivan finds that a constant feature in David Eager Maher’s work is his inclusion of art-history references

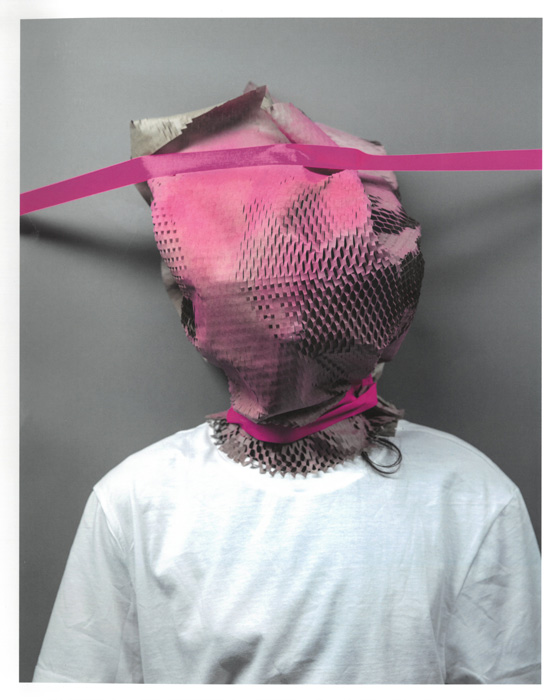

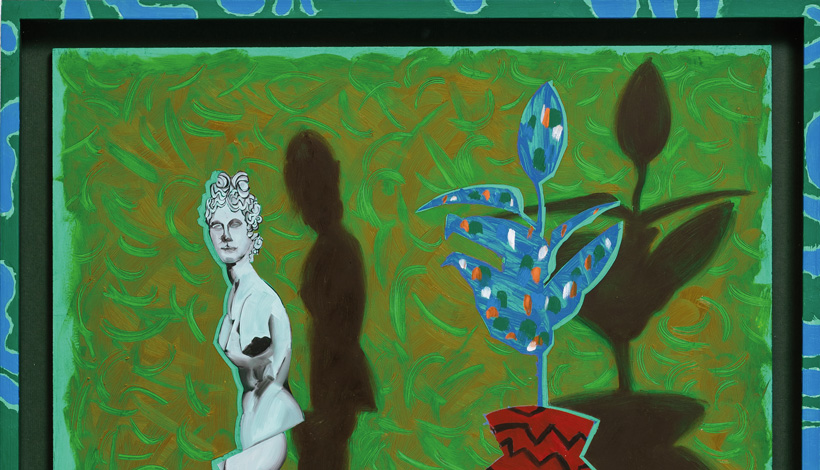

John P O’Sullivan finds that a constant feature in David Eager Maher’s work is his inclusion of art-history references David Eager Maher doesn’t look back – at least not at his own work. He is keen to discuss his new paintings but disinclined to revisit anything earlier. ‘Everything else is gone,‚’ he maintains. ‘Kinda left the building.‚’ In a literal sense this is also true as later he tells me, ‘I’ve pretty much sold everything I’ve made in the past fifteen to twenty years.‚’ Maher’s success as an artist owes much to the quality of his draughtsmanship – the foundation for his strange, off-kilter images. These drawing skills were honed during a prolonged art education that embraced stints in Ballyfermot College, the National College of Art and Design (NCAD) and the Hochschule f√ºr Grafik und Buchkunst in Leipzig. His 2014 feature in Fukt #13, an influential German art magazine devoted to contemporary drawing, brought him to the attention of the art community in that country. ‘It opened up German galleries to me.‚’ His work also chimes with the German appreciation for figurative art and narrative-based painting. Maher has no interest in realism, but at the same time he is vehemently opposed to the glib Surrealist label which is frequently attached to his work: ‘It’s just not relevant to me any more.‚’ His aim is for otherworldliness and the exotic – and for making associations that are apparently disparate but have a sensible logic for the maker. This philosophy of art has been much influenced by the writings of John Hutchinson, former director of the Douglas Hyde Gallery. To read this article in full, subscribe or buy this edition of the Irish Arts Review

David Eager Maher doesn’t look back – at least not at his own work. He is keen to discuss his new paintings but disinclined to revisit anything earlier. ‘Everything else is gone,‚’ he maintains. ‘Kinda left the building.‚’ In a literal sense this is also true as later he tells me, ‘I’ve pretty much sold everything I’ve made in the past fifteen to twenty years.‚’ Maher’s success as an artist owes much to the quality of his draughtsmanship – the foundation for his strange, off-kilter images. These drawing skills were honed during a prolonged art education that embraced stints in Ballyfermot College, the National College of Art and Design (NCAD) and the Hochschule f√ºr Grafik und Buchkunst in Leipzig. His 2014 feature in Fukt #13, an influential German art magazine devoted to contemporary drawing, brought him to the attention of the art community in that country. ‘It opened up German galleries to me.‚’ His work also chimes with the German appreciation for figurative art and narrative-based painting. Maher has no interest in realism, but at the same time he is vehemently opposed to the glib Surrealist label which is frequently attached to his work: ‘It’s just not relevant to me any more.‚’ His aim is for otherworldliness and the exotic – and for making associations that are apparently disparate but have a sensible logic for the maker. This philosophy of art has been much influenced by the writings of John Hutchinson, former director of the Douglas Hyde Gallery.

Peter Somerville-Large recounts the history of the National Museum of Ireland’s significant ethnographic collection, last displayed over thirty years ago

Eileen Black recounts the life and work of Post-Impressionist painter, Georgina Moutray Kyle