[slider_pro id=”168″]

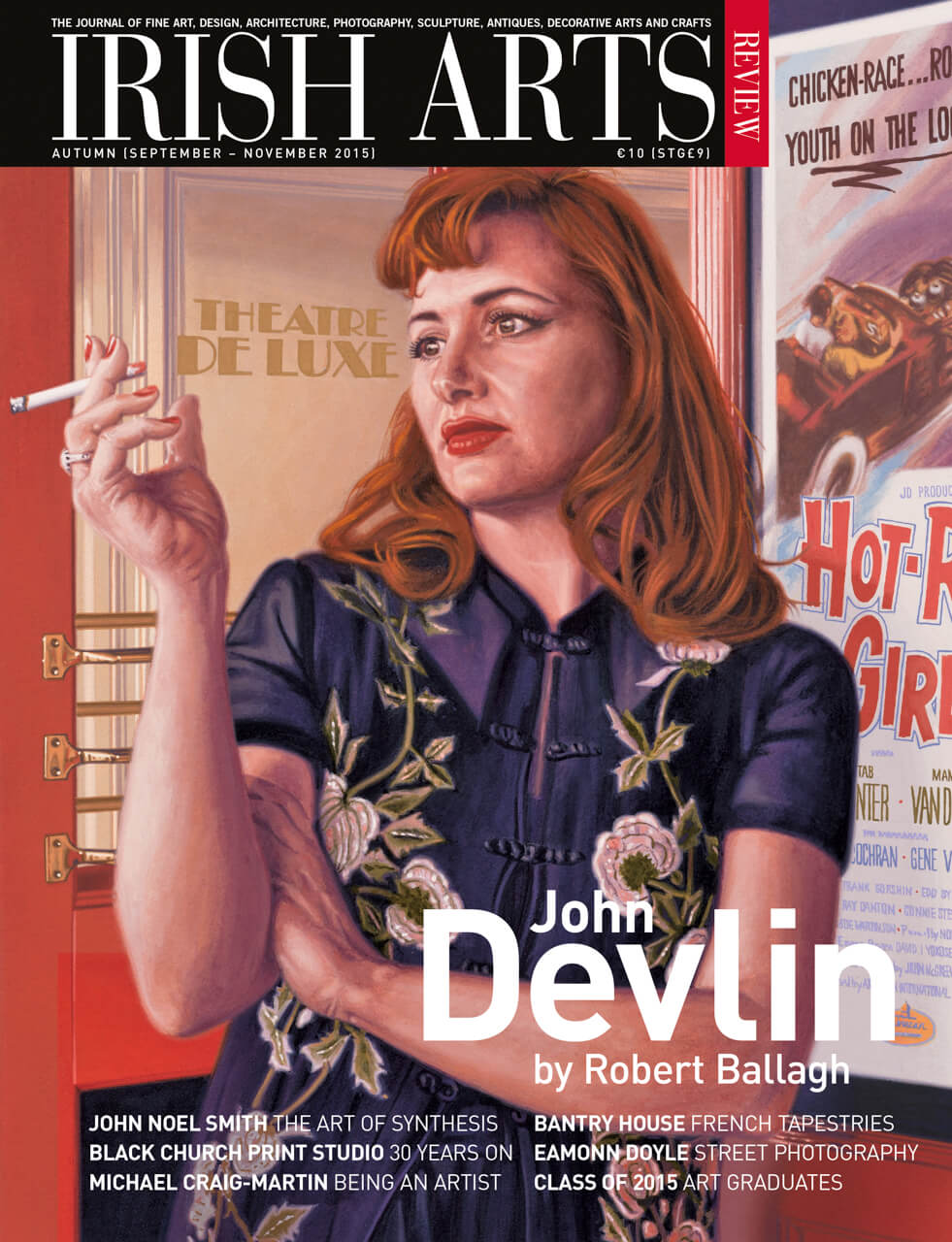

MICHAEL CRAIG-MARTIN

Art/Books, 2015

pp 304 60 col & 33 b/w ills h/b

€32.00/ £22.50 ISBN: 978-1-908970-18-3

Declan Long

On Being An Artist by Michael Craig-Martin is not quite a memoir or a manifesto, though it contains elements of both. The book is a compilation of occasional jottings on art, reproduced catalogue essays and fragments of anecdotal reminiscence; it is Craig-Martin’s collected writings, combined with newly written recollections. Divided into short sections, each headed with a simple title such as ‘On Discovering Art‚’, ‘On Discipline‚’ or ‘On Making a Living‚’ (in all, there are 152 of these subject-specific entries), it feels simultaneously bulky and slight. It’s an in-between sort of book – a characteristic that makes sense, perhaps, given that Craig-Martin is an in-between sort of artist. Since studying art at Yale in the early 1960s, he has been variously influenced by the austerity of Minimalism, energized by the vitality of Pop, motivated by the provocations of Conceptual Art and driven to pursue the lasting possibilities of painting. His work is surely best positioned on the dividing lines between these diverse modes of making and thinking.

The snapshots of a transatlantic life story presented in the book offer some fascinating glimpses of art schools and art worlds of the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, both in the US and Europe.

Craig-Martin’s biography has a notable in-betweenness about it too. Though born in Dublin in 1941, his early years were spent in England (his Irish parents had been based there since the early 1930s). At the end of the War, his father accepted a role with the newly founded World Bank in Washington; and so, at four years old, young Michael and his family emigrated to the United States. He had an American childhood; he was an American teenager; he studied art at a prestigious American college. Later in the 1960s, though, Craig-Martin returned to England, where he gradually gained prominence and influence within the British art scene. By the 1990s, following his retirement from a long teaching career at Goldsmiths College, he was widely acknowledged as the educational Godfather of the ‘YBA‚’ generation of artists who had become such dominant and divisive presences in British art. (Craig-Martin himself is modest about the extent of his influence on Damien Hirst, Tracey Emin, Sarah Lucas et al – sharing credit with fellow tutors such as Jon Thompson and Richard Wentworth – but his respect for the attitude and achievement of his Goldsmiths‚’ graduates is evident throughout.) If the British and American contexts are essential, nevertheless, the Irish connections remain strong. One section – recounting his grandfather’s wry response to an accident at a funeral: ‘it cast a pall of gloom over the whole proceedings‚’ – is entitled ‘On Being Irish‚’. Elsewhere, discussing the only film work he ever made (FILM, 1963), he expresses appreciation for the audience response and institutional support received in Ireland during exhibitions at the Douglas Hyde Gallery and, later, IMMA.

The snapshots of a transatlantic life story presented in the book offer some fascinating glimpses of art schools and art worlds of the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, both in the US and Europe. While at Yale, for instance, Craig-Martin took courses developed by Josef Albers (Albers himself had retired two years before Craig-Martin arrived) which he describes as ‘the summit of high-modernist art education.‚’ Some of Craig-Martin’s Yale contemporaries – including Brice Marden, Chuck Close and Richard Serra – deemed the Albers courses too basic. But Craig-Martin makes a claim for the lasting impact of these classes on himself and others. For him, Marden’s subtle, complex use of colour, Close’s sense of structure and precision, and Serra’s deep understanding of sculptural physicality all have their roots in the Albers courses. And indeed while this book is an often revealing portrait – albeit a fragmentary one – of a profoundly inventive and open-minded artist, whose work has drawn eagerly on the radical innovations of mid to late 20th-century art, it is the sections that discuss art education, or that demonstrate Craig-Martin’s talent as an art educator – that tend to stand out. Outlining what he sees as the ‘three stages of radicalization‚’ in 20th- century art (‘first of form, then of materials, and finally of content), he gives an account that is so clear, concise and coherent, that we can have no doubt how much, and how well, students will have learned from him. A section ‘On the damage being done to British art education‚’ – in which he shows disdain for the language of ‘creative industries‚’ and disappointment at the steady erosion of a unique art school ethos – is written with force and intelligence. Craig-Martin argues that we will ‘eventually pay a price‚’ for the ‘cynical and contemptuous‚’ government attitudes to higher education that have prevailed over recent years. Given his wide-ranging experience in this area, it would be consoling to think that those in power might one day listen.

Declan Long is a lecturer in modern and contemporary art at the National College of Art and Design.