Patrick Scott has certainly established his own particular niche, writes Brian Fallon in his assessment of a uniquely elegant figure in Irish art

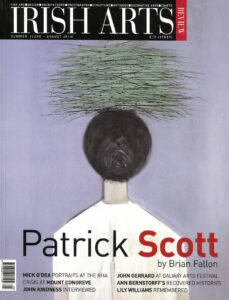

Patrick Scott b.1921 Large Solar Device 1964 tempera on canvas 234x153cm Dublin City Gallery The Hugh Lane

Patrick Scott occupies a special, and even slightly anomalous, position in contemporary Irish art. The latter adjective is not intended to be in any sense pejorative or slighting. It is meant, instead, to imply that while Scott’s career has been a relatively public one, among his generation he somehow resists placing and has no Irish contemporaries who resemble him stylisti ≠cally. It even seems to me that, on the whole, he is not quite what his supporters think he is, and that the occasional hostility he has aroused is also based largely on wrong prem ≠ises. Meanwhile he has occupied a position, which, in the last few decades especially, has become increasingly secure and respected but has never been really commanding. Or to put it differently: he has achieved recognition rather than fame and his is certainly not a ‘glamour’ reputation in the sense that, say, Louis le Brocquy was for half a century. This, very probably, represents more or less the kind of situation he would have chosen himself.

Scott did in fact win a certain reputation quite early in his career, yet in its origins this was little more that a coterie one; was ardently canvassed by an enthusias ≠tic minority, but did not quite ignite the enthusiasm of the average Irish art-lover; was often quoted as an exemplar of the ‘international’ style (whatever that may be in actuality), but while represented in some prestige collections has remained largely an Irish reputation; was simultaneously praised as an avant-garde individualist and questioned as an artistic opportunist riding on the waves of fashion. Now that he is in his nineties and something of a Grand Old Man, the various stylistic and other controversies in which he was, from time to time, marginally engaged no longer seem to matter much, if indeed they matter at ail. Scott has surely established his own particular place or niche, even if he came into full possession of it relatively late in his career.

Some rather odd-sounding claims have been made for him over the years, which on the whole do not add up and may even seem contradictory. A number of commentators have stressed the ‘Celtic’ element in his work, though this sounds to me rather like special pleading.

No doubt such an element exists, but to me it is emphati ≠cally not a dominant one. Other apologists have gone to the opposite extreme and praised him for the purity of his abstract sense and his eloquent formalism; this tribute seems justified, on the whole, but a number of other painters have possessed these qualities without achieving anything gen ≠uinely positive or original. For instance, the late paintings of (the also late) William Scott have a sophisticated minimal ≠ism, which went down very well at the time and even over ≠ shadowed his earlier, stronger and altogether more characteristic work. They fitted neatly (as they were obvi ≠ously meant to do) into the Biennale context of a generation ago but have begun already to look a little thin in content or lacking in energy; in short, they are very much products of their time, and that particular time is past.

Patrick Scott’s earlier career had close links with the Irish Exhibition of Living Art (IELA), with which he often showed in its best years when it still represented virtually ail that was good or relevant in Irish Modernism. He was not, of course, one of its founder-members, but I have heard him speak warmly and respectfully of Mainie Jellett as a person, and the kind of idealism and work ethos she imposed. Chronologically he belonged to its second generation, when the almost overpowering influence of Paris art was begin ≠ning to wane and the so-called ‘international’ style (in fact predominantly American) was gradually succeeding it.

In the early 1940s there had been few Irish abstract painters, and even fewer of any real quality – Colin Middleton’s abstract works, for instance, are stylishly exe ≠cuted but derive too openly from Ben Nicholson, among others. Mainie Jellett’s abstract compositions, though hugely admired today, lean heavily on those of Andre Lhote, Albert Gleizes and similar second-generation Cubists; they have, in fact, an almost academic quality. Other Irish painters of the 1940s and 1950s made occasional forays – some timidly and others foolhardily – into abstraction, but never commit ≠ted themselves to it full-time . There was, in any case, very lit ≠tle public in Ireland for non-figurative art, even if Jack Yeats’ late period can now be seen, in retrospect, as verging on Abstract Expressionism. It was well into the 1960s before abstraction became a common idiom, from which it rapidly degenerated – with some honourable exceptions – into little more than an acceptable cliché.

Scott himself, of course, was a working architect for many years and this factor, so it seems to me (and to others a swell), had a very important bearing on the formation of his style as a painter.

The IELA encompassed a whole range of styles, which is not surprising since Irish artists, like Irish writers, are generally too individualistic to form organized schools. The one common quality which kept its very disparate exhibitors together was the consciousness of being Modern, of being pioneers and of knowing that the bulk of the public viewed them with either hostility or scepticism if it was aware of them at all. Many of them held jobs or positions, since the idea of living as a full ≠ time artist was almost chimerical and the few teaching posts were more or less confined to conservatives, or even downright reactionaries.

Scott himself, of course, was a working architect for many years and this factor, so it seems to me (and to others a swell), had a very important bearing on the formation of his style as a painter. It also brought him within the orbit of the late Michael Scott who had become Ireland’s best-known architect and also a power within the art world – including, inevitably, the IELA with which he was closely identified. This too, in itself, was a major factor which helped to make Scott’s position a more influential but also, in some ways, a rather exposed one. He became identified with some power ≠ful and sometimes dogmatic cliques, now largely defunct, and with a type of ‘designer’ Modernism which was very courant in the 1950s, in particular. Yet, through ail this, he remained essentially his own man and followed his own trail, which has proved to be a long one.

Born in 1921, Scott belonged to a generation younger than, and quite distinct from, that of Patrick Collins, Nano Reid, Gerard Dillon, Daniel O’Neill, Tony O’Malley, George Campbell, Colin Middleton et alii. These painters were pre ≠dominantly figurative but showed an awareness of abstract art, had mildly Expressionist or post-Romantic leanings, and combined French and other Continental influences with pro ≠nouncedly Irish subject-matter. Landscape ranked high among their predilections, though it was a landscape transfigured rather than depicted. Unlike Jack Yeats, who was honoured in France and England and known in America, they have never really achieved reputations outside their own country and remain very little known even in London, where men such as Orpen and Lavery had once achieved a European power-base. (This is doubly curious considering that most of them had either lived or studied abroad for quite lengthy periods and were the reverse of provincial in their mentality).

By contrast, Scott had a ‘cool’ and self-contained manner inclined towards Minimalism (well before the word had been coined), was a restrained, rather circumscribed colourist, and favoured quasi-geometric motifs instead of the sometimes visceral imagery of Reid, O’Malley or Collins. There is a flat and almost tapestried element in much of his work, especially the gold-leaf pictures which became probably his most familiar emblems and are still embedded in the public’s perception of him. Quite under ≠standably, at first many people connected this sparseness with his architectural background and training, seeing in his pictures a linear flatness, dryness and generally schematic approach which derived from it; they also saw a kinship with the artists of White Stag group, such as the gifted but unfortunate Kenneth Hall. In fact, Scott was moving into a much wider context – that of an emerging type of abstrac ≠tion which was wholly different from Action Painting with its characteristically gestural, aggressive methods. Not only Mondrian but early, crucial pioneers such as Malevich were being rediscovered internationally; gestural rhetoric in gen ≠eral was more or less discounted, formal purity, elegance and balance were to a great extent reinstated, and under ≠ statement tended to take the place of overstatement. No doubt certain Bauhaus survivors such as Albers were also influential, particularly in America where a whole new ‘cool’ generation emerged, though this generation also num ≠bered such dynamic, incisive colourists as Ellsworth Kelly.

There is a flat and almost tapestried element in much of his work, especially the gold-leaf pictures which became probably his most familiar emblems and are still embedded in the public’s perception of him

Scott has obvious links with the American School, includ ≠ing his use of unprimed canvas which he shared with Morris Louis, among others. However, it is possibly more of an affinity than a direct influence since the basic qualities of his style had been formed earlier, and he has not attempted to emulate either the scale of American abstract art or its more extrovert qualities. He was not, in any case, a committed abstractionist from the start but developed into it by degrees and successive stages. For instance, some of the early work is close to that of Nevill Johnson, Thurloe Conolly and other local reputations of the time, while a little later he came briefly under the influence of his namesake William Scott. A little later again Scott was attracted to a mild form of Tachism, which can be detected as late as 1963 in Big Solar Device – one of his largest works (Fig 2). By this stage he was working regularly on unprimed canvases and gradually the gold-leaf pictures began to dominate, though not exclu ≠sively. For many people, these remain his most characteristic works and his most typical images.

The gold-leaf pictures also employ tempera instead of oils, and this technique has remained fairly constant. The imagery is almost ascetically simplified – large disc motifs which suggest a glowing sun, quasi-geometric shapes, long golden bands, and (more rarely) areas of parallel stripes, often set against areas of empty canvas; however, in spire of the occasional angularities, the overall effect is reticent and contemplative rather than hard-edged (Fig 3 ). It seems diffi ≠cult to keep Mark Rothko entirely out of the equation, and indeed Rothko’s late, visionary canvases were making an almost universal impact on painters about this time. Which in turn suggests another element in Scott’s later style – the powerful current of Orientalism, much of which spread out ≠ wards from America’s West Coast rather than direct from the Orient proper, and was at its height in the immediate postwar decades. The Action Painters, of course, were thor ≠oughly impregnated by it, but so were many younger men and women and even today it is not quite moribund – as wit ≠ness certain American poets, in particular.

Graves was predominantly a nature mystic, which Scott never was, but I for one have lit ≠tle doubt that he was a major influence on the Irish artist, especially in his later phase

This Eastern ambience seems to have proved highly sym ≠pathetic to a man of Scott’s temperament, and it may well have been reinforced by the presence in Ireland of Morris Graves, one of a remarkable school of painters based mainly in Seattle, the core city of that region of America generally termed the Pacific North-west. Graves had made lengthy vis ≠its to the East, was immersed in Zen teaching and (like his great eider, Mark Tobey) had a quasi-religious approach to his art. During his stay in Ireland, in the early 1960s, he lived mostly near Rathfarnham, on the outskirts of Dublin, and it seems reasonably established that he and Scott got to know one another during this period. Graves was predominantly a nature mystic, which Scott never was, but I for one have lit ≠tle doubt that he was a major influence on the Irish artist, especially in his later phase. However, Graves’ example alone can hardly have oriented him (no pun!) to the art and mentality of the East; he was obviously drawn to it by tem ≠peramental sympathy, and especially to the typical Japanese combination of a broadly decorative element with a delicate, partly nature-based lyricism. The art of the painted Japanese screen, in particular, must have been particularly congenial to him. In Scott, the designer has always been strong and is given perhaps his most typical expression in the very beauti ≠ful Aubusson tapestries he designed in the 1960s and 1970s; it found another outlet in the ‘Tables for Meditation’ which were shown at the Taylor Galleries in 1991. This decade, in fact, proved to be a very significant one for an artist to whom full maturity came a little late.

Scott holds a rather isolated position in Irish art and has had no obvious followers or successors (though the late Cecil King was a possible exception). For one thing, he pos ≠sesses an almost flawless taste, which – let’s face it – is a very un-Irish quality; for another, he is neither a landscapist nor a painter of the figure, two dominant themes for Irish artists over a century at least. Some of his early work, too, was tenuous and rather bloodless, seemingly aimed more at a coterie appeal than a wider public, and this possibly damaged him for some years. His develop ≠ment, however, has been steady and organic over several decades, marked by concentra ≠tion on a relatively limited number of motifs and ideas and by a growing subtilization and enrichment of style.

Scott has learned the art of saying, or at least of suggesting, a good deal by limited, sometimes elliptic means. But – much more positive and to the point – he has a genuine sensitivity for what is beautiful (unfashionable word!), even if it is rather a rarified type of beauty and one which may need time to pen ≠etrate. That, in itself, is sufficient to make him a rara avis among his contemporaries, both at home and abroad.

‘Patrick Scott Retrospective at IMMA, Dublin & VISUAL, Carlow 23 February – 2 June 2014.

All images © The Artist

Brian Fallon is the Editor of Conor Fallon, Thoughts on Sculpture 12011)