Hilary Pyle takes a fresh look at John Butler Yeats, the patriarch of Ireland’s leading artistic family.

Since William Murphy published his biography of John Butler Yeats (JBY) Prodigal Father, critical assessments of the artist have tended to stress the pejorative quality embedded in the title. ‘Prodigal’ is generally used to described those who are ‘recklessly wasteful, extravagant, or spendthrift’ – though no doubt with the underlying possibility of redemption – and may suit to describe a small element of the subject’s character. To the modern mind, particularly, JBY’s total disinterest in money led him to be neglectful of those who depended on him, and temporarily importunate on those who were more wealthy than himself. On the other hand, to his own way of thinking, he was giving his family – his children anyway – more than money can buy, by abandoning a secure profitable profession to pursue a life where natural gifts were his resource and livelihood, and he enabled and indeed exhorted them to do the same.

He wasn’t the only artist of his day – or in history – to be financially incompetent. It was hard on his wife, for whom it would have been difficult whatever happened, for, as he frequently observed, their families were diametrically opposed in their attitude to life; but he was always true to her, remaining close to her throughout her years of incapacitation, and he always focused on what he believed to be good and positive in their relationship.

His lack of monetary competency was something he would always have to struggle with. Strange though it may seem, those of his contemporaries who criticized his profligate attitude made no effort to persuade him to look for a realistic financial return. Instead, while appreciating the inimitable quality of the painting, they were happy to take advantage of his cavalier attitude. Even towards the end of his life, he wrote to an American friend, ‘I do not make much money (I never do). My contract was for one portrait & I painted the others [three portraits] for friendship’s sake.’

As AE reminded John Quinn, almost a year after John had set out on his journey of no return, leaving Ireland for America, the artist’s daughters called JBY their ‘Pilgrim Father’: and this term is more apt in every way than ‘Prodigal’, because from the start of his life JBY was a seeker and philosopher, forever analyzing people (especially himself) and situations, assessing contemporary art and his own art, theorising on every topic.

He was also an experienced traveller. In Early Memories, written while in New York and published posthumously by Cuala, he relates how, as a very young boy, his uncle accompanied him from his home in County Down to Liverpool to start his education at a school run by three Puritan ladies. He regarded it as his introduction to duty, misery, and high principles, as well as to Hell. Previously he had been conscious of the loneliness of childhood – and ‘the blessedness of it’. ‘I was always by myself, therefore I early learned to sustain myself by revery and dream.’ When he was ten, he moved to the Atholl Academy in the Isle of Man – this time two younger brothers came with him. The headmaster, a Scot, ruled with a rod of iron, and terrified the boys: yet, even at the time, JBY could understand reasons for it, and could see his merits, as he did in most of the people he constantly questioned and evaluated.

At Atholl he met George Pollexfen, a solitary like himself – though melancholy, the exact contrary to JBY who was by nature perennially hopeful. The two opposites became firm friends, and Yeats would marry Pollexfen’s sister. He came home only for six weeks in the summer, and describes his evangelical father as ‘his friend and counsellor’, and his frugal mother as ‘his conscience’. The latter begrudged him the highly taxed drawing paper which his father gave him in abundance, encouraging and praising what he did. The hours he spent as a boy with his reverend parent, who smoked his clay pipe in the rectory kitchen at night, were remembered throughout his life with gratitude. In turn, he would spend time with his own eldest son, cogitating, theorising, formulating an intellectual framework for life, well embellished with colourful aphorisms.

Following in the family footsteps, and in the expectation of being ordained for the Church of Ireland ministry, he went to Trinity College in Dublin, where JBY studied metaphysics and logic. Here he lost his interest in orthodox religion, partly because of his interest in Comte and Mill, and the latter’s polemical influence on himself, ‘which I shall now never get rid of’, he wrote late in life; though he admitted that his dreaded Scottish schoolmaster was responsible too. He took up law, devilling for his father’s old friend and fellow student, the Home Ruler, Isaac Butt (Fig 2). Yeats’s oratorical gift led to his becoming Auditor of the Law Students’ Debating Society of Ireland. With his personal charisma and fascination with people, he injected new purpose and energy into the society at a time when it was waning. The lecture hall at the King’s Inns, on the night of his inaugural address, was bristling with QC’s, VP’s and Professors; and an eminent Judge proposed that the paper be printed and circulated at the expense of the Society.

The paper, on the subject of ‘The true purpose of a debating society’, was laced with lofty sentiments that echoed Mills in particular, calling for the debating society Yeats envisaged to engender the practice of sowing noble thoughts and purposes in men’s hearts and consciences. The words were delivered with the solemnity and fire of a sermon. Oratory and eloquence, he declared, were nothing without the attainment of truth. This juvenile aim remained with him for the rest of his life: his last essays and letters show him to be invariably consistent, never losing his idealism, or his ingrained humanism.

John Yeats’s natural expertise as a draughtsman, well fostered at school, was to be his downfall in court, where his spontaneous caricatures of the judiciary provided entertainment on the side during trials. One example found its way into the wrong hands, and, encouraged by the response of the editor of Fun to some examples of his work he had previously sent him, he decided abruptly to abandon law and try his hand as an illustrator in London, at the same time as training to be a professional artist.

He arrived at one of the strongest periods of black-and-white art in England, where, because of improved printing techniques, many of the best artists, for instance Richard Doyle of Punch (who admired his first paintings), earned handsome salaries with pens rather than with brushes. As it happened, while he did earn a modicum from his contributions to Fun, he never looked for other commercial opportunities, and instead devoted himself to acquiring skills for oil portraiture at Heatherley’s Art School.

At the time he thought George Watts, then at the height of his popularity, ‘the greatest figure-painter England has ever produced’ (‘whose Eve was so real that you feel almost that you could touch her golden flesh, and hear her cries and murmurs of delight’), and a quick visit to Antwerp with his college friend, John Dowden, gave him a first hand view of early Netherlandish oil painters and their meticulous clarity. With a group of students at Heatherley’s he formed a ‘Brotherhood’ to revive the ideals of the Pre-Raphaelites, particularly Rossetti and Morris, and Rossetti was a noticeable influence on John Yeats’s work in these first years (Fig. 3).

He was diffident when it came to meeting the artists he admired, even when – having seen his work – they called at his studio. He always avoided them. At the same time the need for regular colloquy with creative minds was vital to him throughout his life. He now knew for certain that Art was his métier, but – with a minimum of confidence in himself, and a personality ‘never prey to commercial rage’ – he relied on sympathetic friends for both practical and artistic advice, however much he might ignore the advice when he received it. Intellectual conversation did stimulate him while he worked, and in the evenings he liked to relax and debate with likeminded intellectuals, whether about culture and politics (Home Rule was believed to be imminent) at the Contemporary Club in Dublin in the 1880s or literature and current affairs at the Calumet in Bedford Park, during the 1890s. He had to have company, thriving in the midst of which he was able to detach himself, and retreat back into solitude.

While a student at the Heatherley, and then at the SlaJBY undertook commissions of various kinds, including the copying of portraits at which he was particularly adept, and invitations as itinerant portrait painter to Killarney, Richmond and other places. These were traditionally menial jobs for which he had little heart, and his unbusinesslike attitude was no help. He liked to paint ‘fancy’ (imaginative) subjects. For portraits, he preferred members of his family as his sitters: he sketched and painted them continually from birth to adulthood (Fig. 4).

His commissions usually came from Irish sources (which may be one reason why the Royal Academy in London showed little interest in him), so John Yeats returned to Dublin in the Spring of 1880. The Royal Hibernian Academy had accepted what he offered. For the next few years he exhibited there regularly, moving his family back to live in Howth, sending Willy to High School and the girls to the Metropolitan School of Art. At every move in his peripatetic career he was convinced that, given a new start, he would at last begin to make his fortune. His university contacts was still yielding clients. He Joined the Dublin Sketching Club, and helped to bring Whistler to Dublin, undoubtedly learning from him how to manage his tonality and reduce pigment. It was probably through him that William Morris came to speak to the Contemporary Club; Gerald Manley Hopkins visited at his studio to discuss his theories about art; and, in the Autumn of 1886, with Walter Osborne and Sarah Purser, John Yeats founded the Dublin Art Club.

Sarah Purser, continually versatile, found work for him and Nathaniel Hone painting decorative panels for Sir Patrick Dunn’s Hospital, and Yeats commenced work on a commission from the Contemporary Club to paint John O’Leary, which he was enjoying – it would be the first of three portraits of the aging patriot and exile, his favourite sitter apart from J. M. Synge, not least on account of their conversations. His eldest son Jack was making his name as a poet, and John Yeats occupied himself enthusiastically, forging a public image of him, sketching and painting him in poetic attitudes, some of them becoming frontispieces to Willy’s first books.

There was inevitable stress at home as the young adult was beginning to question his father’s capability in managing his career. The tension was not lessened by the crises in land reform, which affected John’s inheritance, the small estate in Kilkenny which generated a regular, if meagre, income: so he decided to sell, a decision resulting in a distressing legal situation that would continue for years. Perhaps to put distance between himself and his financial worries, and because Jack (Fig 5), brought up largely by his grandparents in Sligo, was to rejoin the family and embark on his art school training, he determined to make another new beginning. Back in London, he attempted to reinsinuate himself into the profession of black and white illustration – in its final flowering before photography displaced it; and here, at least, was a profitable career, he hoped.

No one had envisaged that his wife, Susan, would have a stroke as they were in the process of moving, and then another stroke: and so began the journey through what can only be described as the desert in his pilgrimage, the artist never ceasing to blame himself for her illness. Settled in London with the family, now launching on their own careers, he began contributing to Good Words and Leisure Hour, work for reproduction that would never appeal to him. There were brighter moments. The Royal Academy accepted a watercolour for the 1887 exhibition, and he was elected an Associate of the Royal Hibernian Academy, who showed his portraits of O’Leary, Rolleston, George Coffey and Kathleen Tynan – his last exhibits until 1891. Then his second oil portrait of John O’Leary appeared in Dublin, a calm, reflective image.

His intellectual stimulation in Bedford Park came from the company of close friends such as G. K. Chesterton, York Powell and Elkin Mathews. He could indulge his love of words perpetually, in conversation, in letters – sometimes in short stories. The Calumet Society met on alternate Sundays at the homes of its members. It was at 3 Blenheim Road, Yeats’s house, that the first meeting to discuss the founding of the Irish Literary Society (a crucial moment in the history of Irish nationalism) was held.

He still sketched people, as he talked, and made illustrations, the most important commission being from J M Dent of Temple Library publishers to illustrate the complete works of Daniel Defoe. His daughter Lily acted as model for all except Man Friday, and would bring the drawings to London: though she grieved, ‘Old Dent used to shed tears at the beauty of the drawings, and then used to pay me the miserable cheque for them.’ Her father, nonetheless, liked this work, and could write to her, ‘I now use models for everything – this using of models is a great discovery.’

For seven years, he did not lift a brush. He drew and made watercolours; but he was unable to paint. The period of aridity was partially genetic: but the problem also related to a deep inner frustration, and the need to revitalise his work. Fortunately, Lady Gregory commissioned a gouache portrait of WB Yeats, and then a series of pencil portraits of Hyde, and others, which occasioned his returning to Dublin in 1898, where Sarah Purser found him a teaching job for the summer in May Manning’s studio. By the following year his brush was active again. He painted all the time, his family (Fig.6) as regular subjects, loosening his brushstrokes to create the lofty dreamlike spirit that was to infuse all of his Irish Renaissance portraits.

For John Yeats, drawing had always been spontaneous and immediate. Now he knew that his painting must be likewise: he must ignore academic procedures and paint as if he were drawing. Contemporary trends such as Art Nouveau, or the prophetic attitude of the Nabis, had no attraction for him. To him, the quintessential model for modernism was Impressionism. He shared the Impressionists’ belief in the importance of Truth, and their maxim – to capture the first impression. His work in oil now needed to be ‘struck off at a first heat,’ he told his son. So each of his oils at the turn of the century, including his magical portrait of Willy (Fig.7), were completed at a single sitting, to maintain the ‘first heat’.

The confinement to which he had resigned himself for years came to an end in 1900 with the sudden death of his wife. Yeats was now free to move about at will. He visited Paris and went down to Devon to Jack. In London he attended the Romney exhibition with Sarah Purser and Edward Martyn.

Purser was anxious to have him back in Dublin. His stunning new portraits of Lily and Lolly had been rejected by the Royal Academy in London, and she would exhibit them, with a range of his earlier and more recent work, in a joint exhibition with Nathaniel Hone whom she thought had also been neglected by the art world. Every one who visited the widely attended exhibition in October 1901, was impressed by both artists. The Irish Press likened Yeats’s portraits to Rembrandt, who ‘takes a head and hangs it in the infinite ‚Ķ there is the whole mystery of existence’. The exhibition brought welcome (at first) business to JB Yeats. He had two enthusiastic patrons: John Quinn, fresh from New York, and Hugh Lane, so inspired that he decided to establish a permanent modern gallery for the city. To begin with Lane, he produced a list of twenty personalities he would like represented on its walls, figures crucial to the arts and politics of an Ireland alight with the prospect of freedom, and he asked John Yeats to paint them.

The sixty plus painter’s sudden plunge into the creative surge in Dublin would not have to be endured on his own. Evelyn Gleeson, expert in Irish crafts, had invited the Yeats sisters to join her in founding a women’s cooperative, on the lines of Morris’s Kelmscott, in Dublin; and the whole Yeats household moved over from Bedford Park, in the summer of 1902, to live in Dundrum. William too became involved in the management of the Dun Emer Industries.

After initial difficulties in finding a studio, J. B. Yeats settled to work on his new commissions. Conversation created ease with some characters, with whom he had little in common: but other sitters, especially the impatient, made him uncomfortable and stressed, and there the trouble began: because he was forever scraping out and delaying completion of the work, in the hopes of pleasing both them and himself – thus dismissing his resolve to preserve ‘the first heat’ of his inspiration. In addition, his early need to explore imaginative themes reasserted itself, and he was painting panels of Summer and Spring – ‘These panels mean reputation’, he told Lane.

His most successful canvases (and most enjoyed by him and his sitters as he painted) were of thinkers, writers, actors, and poets – he had little sympathy for politicians. Contemporaries remarked that his oil portraits are more than mere likenesses – and this is true, and not only in their immediacy, and the sensation of individual presence that pervades each one of them. Collectively, they put across the visual story of a unique time, when, there was ‘not a single name in literature or art which was not identified with Irish nationalism.’

It wasn’t long before Yeats – at last recognised as an exceptional artist, his studio a honeypot for any one in Dublin, or from abroad, interested in art – found his commitments overwhelming. He continued to paint incomparable portraits – of leading Abbey actors, of AE (Fig 8) and Synge (both of whom he loved for their conversation, Synge’s ‘so rare and sudden’), of Moore, O’Grady and other writers, among others – but at his own pace. For Yeats, ‘Every artist knows how difficult it is to make up one’s mind that a picture is finished, for it is never finished, for it is never perfect, and perfection is the artist’s goal.’ Lane, however – a mass of energy – wanted results, and promptly. He had no interest in J. B. Y’s fancy pictures, only wanted his portraits. He also suggested a lecture in Belfast – the idea of which sent the artist into paroxysms: ‘my mind won’t work for me at such a thing as lecturing or indeed at anything if I am oppressed by worries.’ Lane responded by asking the artist’s rival, young Orpen (whom Yeats dismissed as having ‘a little too much of God’s hammer about his work’), to take on the more meandrous portraits.

‘My portrait of Judge Madden is a failure’, he confessed to his patron in March 1907, ‘ he would not let me have my own way’. Worse still, Lane installed an Italian painter, Antonio Mancini, whose modernity owed much to gimmickry, in Clonmell House, the premises of the proposed modern gallery: and he capped it all (insulting J. B. Y. still more), by raising a sum of money to send him to Italy.

As Lady Gregory exclaimed shrewdly, the artist did not work well in bonds, and Yeats would have nothing to do with such a plan. Suddenly – once more disdaining patronage in his idiosyncratic way – he used the money to buy a ticket to New York, and travelled with Lily who was going on Cuala business.

The final portrait of John O’Leary, painted by John Yeats in 1904 (Fig. 9), his wide-brimmed traveller’s hat balanced on a large book, is an interesting precursor to the artist’s own Self-Portrait with Hat, painted shortly before he left for New York. O’Leary gazes from the oil calmly, with wise experienced eyes, while in his gouache Yeats inclines his head in a position of enquiry, holding his pilgrim’s hat in readiness to put on his head.

On their arrival in New York, John Quinn and his hospitable circle wined and dined the old artist and his daughter. Lily delayed her return for her father, then eventually came home alone, as he was determined to stay on for a while. Yeats was in his element, feted for a period, then – abandoned when he ceased to be a novelty – he prepared to sustain himself in ‘blessed’ loneliness, ‘by revery and dream’. ‘Art is Dreamland,’ he told WB, ‘We all live when at our best, that is when we are most ourselves in dreamland. ‚Ķ Pronounce it to be actual life and you summon logic and mechanical sense and reason and all the other powers of prose to find yourself hailed back to the prison house, and dreamland vanishes.’

He rented a room with board from some Bretons, also in exile, the Petitpas sisters – his final dwelling; and he fell in with the similarly anti-academic, though conservative group, the Ashcans, and exhibited with them. Viewing the French and other avant garde artists in New York’s Armory Show, in 1913, he was scathing in his criticism. Even though, and typically eager to maintain a contemporary touch in his painting, he had already advanced his style further into what might be called his post-modern style, the forms (even in drawing), more firmly enunciated, the colours denser and more vibrant (Fig. 10).

Conversation and pencil portraits were still his mainstay. He sketched at table now, and in cafés, and for absurdly modest returns. Freed from responsibilities, he indulged his pen, ‘learning to write’, as he said, eventually publishing articles and stories, which probably substituted for the fancy pictures he needed to paint. Towards the end of his life, Cuala would publish selections from the innumerable letters he wrote to his family and friends at home. From a distance he was in regular communication: the only one of his children he ever saw again was Willy, travelling with his poetry.

The final Self Portrait (Fig 1) commissioned by Quinn, who still looked after him, preoccupied him from 1911 until his death. ‘In his letters,’ Willy wrote in his preface to Early Memories, ‘he constantly spoke about this picture as his masterpiece, insisted again and again ‚Ķ that he had found what he had been seeking all his life. This growing skill had been his chief argument against return to Ireland, for the portrait that displayed it must not be endangered by a change of light.’

JBY died in New York on 3 February 1922 aged eighty-three and was buried at Chestertown Cemetery in upper New York state. In 1972, the National Gallery of Ireland held an exhibition of 138 of his paintings and drawings with a catalogue by James White.

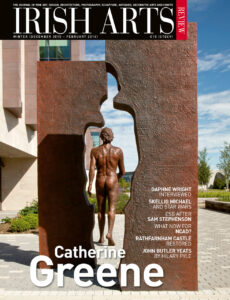

‘At A Glance: Portraits by JBY’, curated by Niamh MacNally, National Gallery of Ireland, until 17 January 2016.

Hilary Pyle is an art critic and writer.

1 To Mrs Simeon Ford, 9 August 1916 (National Library of Ireland MS 35988).

2 A. Denson, Letters from AE. London, Abelard-Schuman, 1961, p. 65. 1 Oct 1908: ‘I recommended them to cable, ‚ÄúFamily all dying. Come to receive last messages‚Äù.’

3 Early Memories: Some Chapters of Autobiography. Dublin, Cuala Press, 1923, p. 57.

4 Essays Irish and American, Dublin, Talbot Press, 1918, p.85. The essay on Watts was first delivered as a lecture at the RHA in Dublin, in Spring 1907.

5 Pippa NGI (Fig 5), inspired by Browning’s poem.

6 Derek Mahon, ‘Imbolc’, in The Hudson Letter, Meath, Gallery Press, 1995.

7 Elected a full member of the Royal Hibernian Academy in 1892.

8 W. M. Murphy, Prodigal Father: The Life of JBY 1839-1922, Cornell University, 1978, p. 182.

9 JB Yeats, Letters from Bedford Park, 1890-1901, ed. W M Murphy, Dublin, Cuala Press, 1972, p. 17

10 Both of his sons experienced the same predicament as mature artists.

11 H Pyle, ‘Drawing into oil: John and Jack B Yeats’ in Prodigal Father Revisited, Locust Hill Press, 2003, p.178

12 H Pyle,The Renaissance of Mr Hone’ Irish Arts Review (Spring 2015), pp. 110-113.

13 JB Yeats to Hugh Lane, 13 January 1904, National Library of Ireland MS 35823.

14 Denson, A, Letters from AE, p.127.

15 John Yeats, Essays Irish and American. p. 51.

16 See W M Murphy, op. cit., p. 116.

17 John Yeats to Hugh Lane, n.d. [April 1906].

18 J. White, JBY and the Irish Renaissance, Dublin, Dolmen Press 1972, pp 13-14