Rachel Thomas interviews Richard Malone, an artist who works across the media of sculpture, fashion and performance, pushing the boundaries of traditional sculpture.

Rachel Thomas: Richard, how did growing up in the rural landscape of Wexford in the 1990s influence you?

Richard Malone: I’m from a working-class family of labourers and makers, and I moved from Wexford town to Ardcavan when I was about six. I was the second in my family to get the Leaving Cert and go on to third level. I never had access to art growing up, but I had endless access to imagination – mainly as a response to boredom. I was fascinated by people, drawing 24/7. I always had this compulsion to make and to create with anything I got my hands on: trying on my mam’s clothes, draping fabric around me, building, playing with Polyfilla, drawing. I made rosettes and knotted bracelets with my grandmother to celebrate the horse shows or the GAA.

Engaging with your independent artistic voice is the single best education you can have – no MA or PhD comes close to experience and play. Freedom in itself is a real education. Ireland has this formal approach to education, defining who gets to show. It’s become a prerequisite when not everyone can access it, and that’s a problem.

I became very aware of the performance of gender early on. I worked with my dad on building sites, and when I was younger I learned sewing and painting with my grandmother at home. The distinction between those spaces in terms of materiality always stayed with me – from steel, wood and concrete to linen, cotton thread and sewing, or to language, or gesture, or silences.

Angela Griffith appraises Paul MacCormaic’s painting of Lucky Khambule, this year’s winner of the Ireland–U.S. Council and Irish Arts Review Portraiture Award

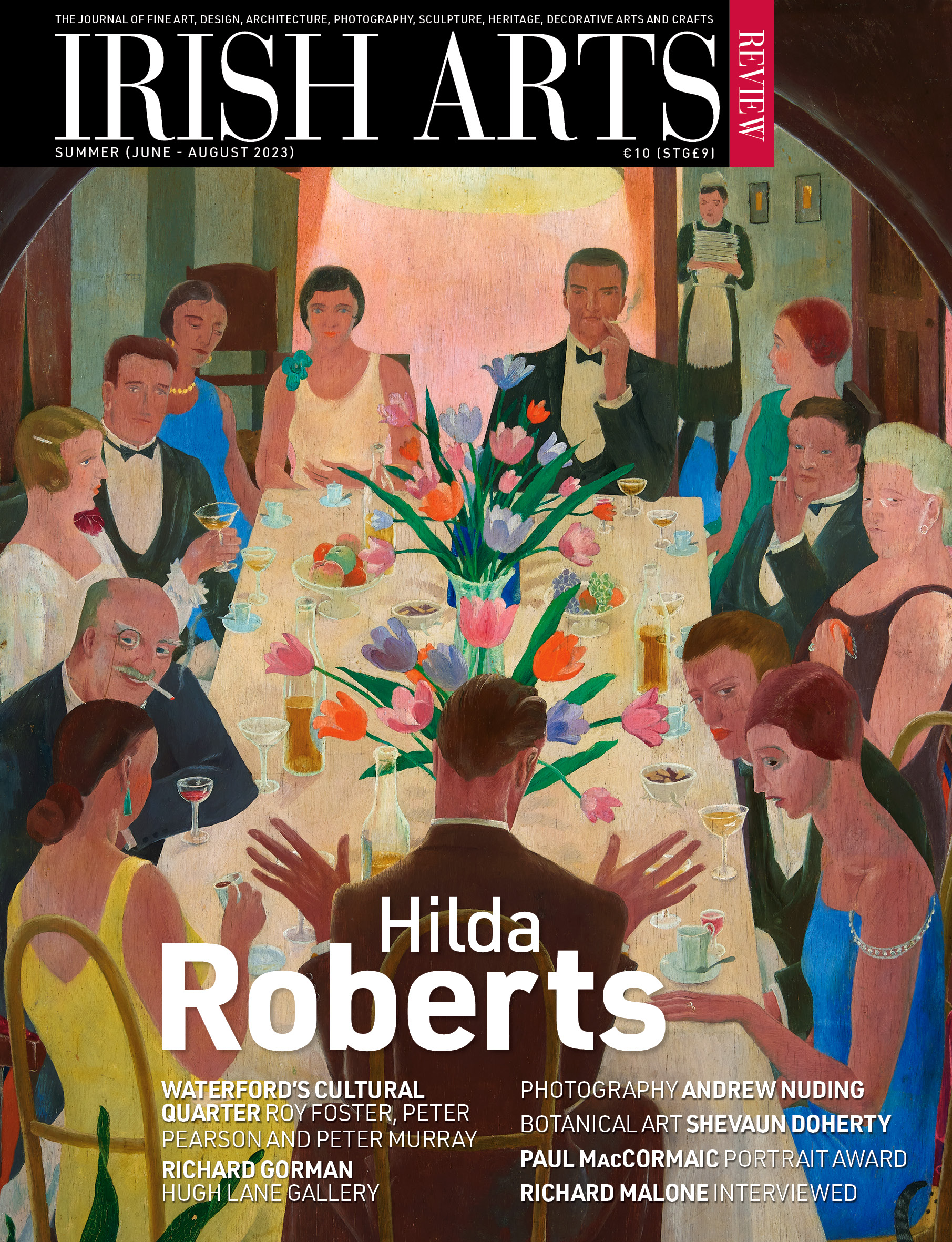

Hilary Pyle recalls the artist Hilda Roberts, two-time winner of the RDS Taylor Art Award, whose talents were apparent from an early age

Aidan Dunne visits the survey exhibition of painter Richard Gorman at the Hugh Lane Gallery