Donal Maguire reflects on the power of portraiture in his appraisal of this year’s winning portrait for the Ireland-U.S. Council/Irish Arts Review Portraiture Award

It fascinates me constantly that, despite the apparently unlimited pluralism with which we have come to perceive and define art, and the persistent blurring of distinctions between approaches to art making, portraits continue to occupy their own distinct niche within the realm of visual culture. The most obvious manifestation of this is the physical separation of portraits from other types of art into collections and dedicated galleries, the most visible examples being national portrait collections and portrait museums. It would seem portraits, in this sense, are accorded special treatment by our society, the reasons for which are rooted strongly both in the traditions of the genre and the expectations of the contemporary viewer.

Portraits are inextricably linked to the identity of a real person and the subject of the artwork is often prioritised over its more aesthetic qualities – as art historian Richard Brilliant has observed, there is ‘a great difficulty in thinking about [portraits] as art and not thinking about them primarily as something else, the person represented’. When we look at a portrait, or visit portrait galleries, our focus therefore tends to lean, or be directed towards, contemplating or imagining the true nature of the portrait’s subject, this real person. We look at a portrait and instinctively ask, ‘who is it?’

It fascinates me further that, despite the extreme proliferation of portrait images in contemporary life and the ability of almost anyone to now make a portrait (photograph) of their own, the genre continues to be one of the most popular forms of visual art. What’s more, despite the apparent constraints of portraiture, its traditionalism and mimetic nature, the practice continues to appeal to even the most experimental of contemporary artists. In the work of artists from Brian O’Doherty to Marc Quinn and Tacita Dean, the art of portraiture has been employed by artists as a vehicle for exploring often profound political and cultural discourses associated with the politics of identity. The very constraints of the genre, its seems provide the creative tension that is often required (and so often absent in other art forms) for artistic invention and experimentation.

Portraiture’s popularity in Ireland has no doubt been helped in recent years by the emergence of high-profile portrait prizes such as the Zurich (formerly Hennessy) Portrait Prize at the National Gallery of Ireland as well as the longer running Ireland-U.S. Council/Irish Arts Review Portraiture Award, presented at the Royal Hibernian Academy’s Annual Exhibition. Established in 2006, the latter was created to promote and ignite greater interest in the portraits displayed at the annual exhibition, and to support artists who explore and expand its role and potential within contemporary society. Previous winners include Maeve McCarthy 2006), Gary Coyle (2007) and Geraldine O’Neill (2015).

It is tempting to interpret Rackard’s portrait in high-concept terms, simplifying the image combination to a representation of dual identity, gender fluidity or a before-and-after juxtaposition. Rackard’s work is, however, more interesting than that, both in its exploration of gender and the process of its creation

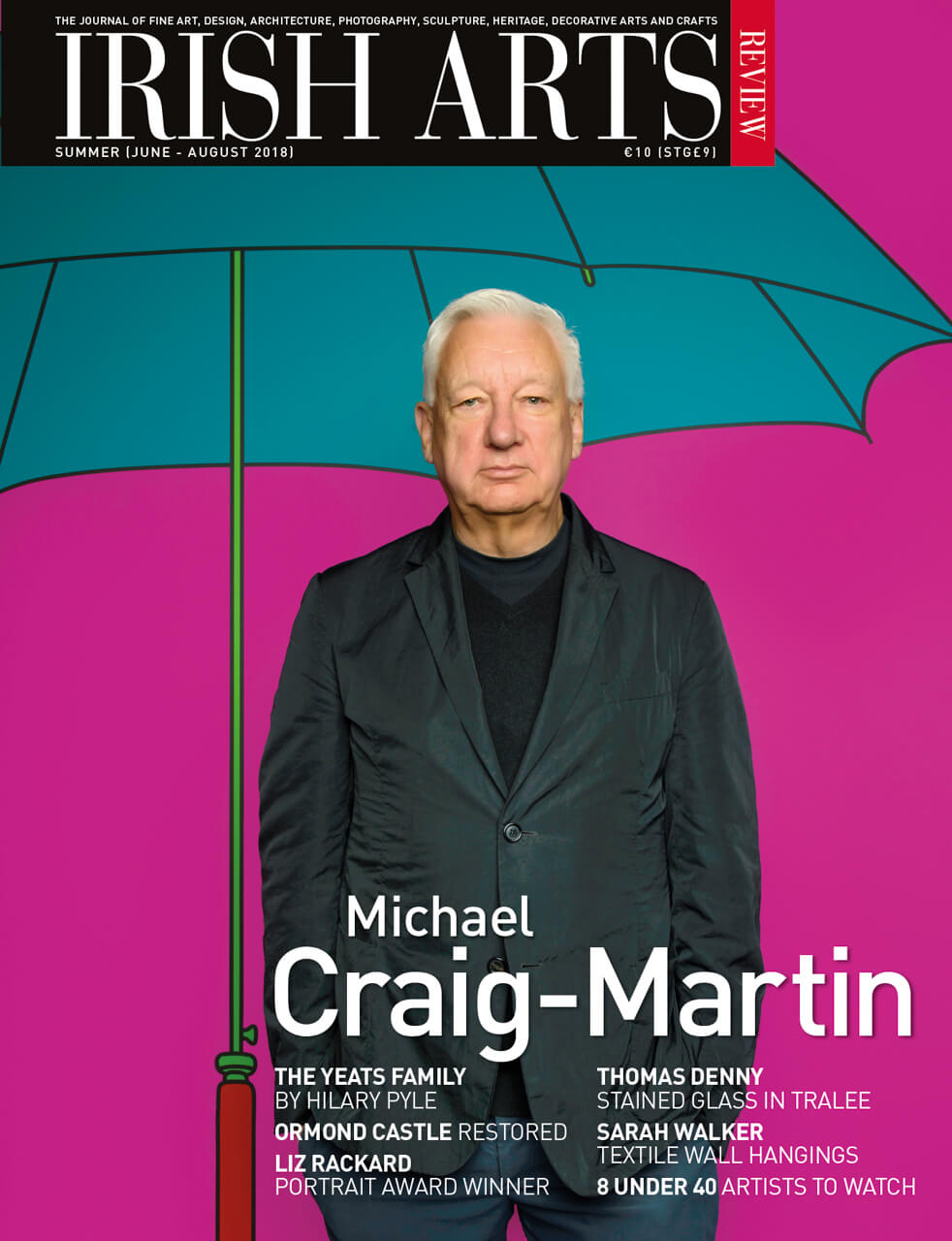

The 2018 recipient of the portrait prize is Liz Rackard for her portrait Eoghan. Trained initially in textile design at the National College of Art and Design, Rackard has worked in diverse aspects of the arts throughout her career from textile dying to illustration and fine art. It is only in recent years that she has developed an interest in portraiture. Working on a small scale and in miniature, Rackard began to make family portraits before taking on commissioned work. Her portrait Eoghan is striking in terms of its approach to portraying its specific subject. Eoghan comprises two square canvases, hung side-by-side and separated by a small gap. Painted in flat brushstrokes and even colours, the low contrast images depict head and shoulders portrayals of a single sitter in a format resembling a standard ID or passport photograph. Despite their diminutive scale, relative to the paintings flanking them, Rackard’s portrait possesses a strong presence in the room – the two faces staring directly out of the canvas.

The portraits two distinct images seem to depict two different sitters, both youthful in appearance, one looks to be typically female, the other male. Such gender assumptions are of course entirely based on preconditioned notions of masculinity and femininity, associated with particular types of clothing, hairstyles, make-up and so forth. One of the sitters wears earrings, a floral-patterned top and red lipstick, the other wears a blue t-shirt and shows facial stubble. Rackard’s double portrait, however depicts one person, Eoghan, an individual on the cusp of adulthood. It is tempting to interpret Rackard’s portrait in high-concept terms, simplifying the image combination to a representation of dual identity, gender fluidity or a before-and-after juxtaposition. Rackard’s work is, however, more interesting than that, both in its exploration of gender and the process of its creation.

Although the two images now form one artwork, they were created separately, originating under different circumstances. The earlier portrait, in which Eoghan appears as a young man was painted on commission at the request of his family. The following year, Rackard, a family friend, requested Eoghan to sit for a second portrait, this time dressed in one of the other styles of dress and appearance that he enjoys – one more typically perceived as feminine. After acquiring both works from Rackard, Eoghan’s family began to hang the pictures side-by-side. When hung together they formed a new portrait of Eoghan, one that captured different aspects of the identity of this young individual.

In her portrait of Eoghan, Rackard makes no attempt to form any grand statements on gender or sexuality, instead, she simply presents two differing images of the same person. For Rackard, herself an art therapist who works regularly with young people, the juxtaposition of the two images suggests a more complex sense of identity that she hopes will raise questions, such as, where does identity lie? Is identity static or constantly in flux? In this respect, Rackard’s portrait of Eoghan does not represent any particular notion of identity but rather it evokes the many changes and transitions that individuals undertake in their journey through life. ‘

RHA 188th Annual Exhibition, RHA, Dublin, until 11 August 2018. This year marks the 13th annual Ireland U.S. Council/Irish Arts Review Portraiture Award.

Donal Maguire manages the ESB Centre for the Study of Irish Art at the National Gallery of Ireland.