Síghle Bhreathnach-Lynch remembers a leading member of the Celtic Revival, artist Mia Cranwill

Síghle Bhreathnach-Lynch remembers a leading member of the Celtic Revival, artist Mia Cranwill

A resurgence of interest in handicrafts and the art of design in Ireland was stimulated in the 1880s by the English revival spearheaded by artist and textile designer William Morris. However, in Ireland the movement was as much affected by political and cultural concerns as by the making of functional objects. Artists, literary and visual, looked to ‘pure’ native sources for inspiration. Organisations and ventures were initiated by progressive and idealistic Home Rulers. For those involved in the arts and crafts, early Celtic designs in manuscripts, in metalwork and on sculpted crosses were major sources of inspiration.

Mia Cranwill was a leading member of the Irish movement. She first distinguished herself by creating jewellery that interpreted early Irish designs with a new aesthetic. By the 1920s she was firmly established at home and abroad, largely as a result of two commissions, one for St Patrick’s Catholic Church in San Francisco, the other for a casket marking the setting up of the first Senate of the Irish Free State. A decade later she had contributed to Titania’s Palace, a famed miniature castle, and executed a trophy for the Catholic Boy Scouts of Ireland, embroidered by Cuala Industries. In the 1950s, her friend Liam Millar of Dolmen Press commissioned her to illustrate a number of its publications. An article in the Irish Independent about the artist (20 November 1954) compared her to a 16th-century Italian metalworker and sculptor, calling her ‘the Benvenuto Cellini of Ireland’. However, like a number of women artists of the period, she quickly faded into the hinterland of Irish art history.

To read this article in full, subscribe or buy this edition of the Irish Arts Review

Aresurgence of interest in handicrafts and the art of design in Ireland was stimulated in the 1880s by the English revival spearheaded by artist and textile designer William Morris. However, in Ireland the movement was as much affected by political and cultural concerns as by the making of functional objects. Artists, literary and visual, looked to ‘pure’ native sources for inspiration.

Joseph McBrinn charts the history of Evie Hone’s Tullabeg windows, which illustrate scenes from the life of Christ

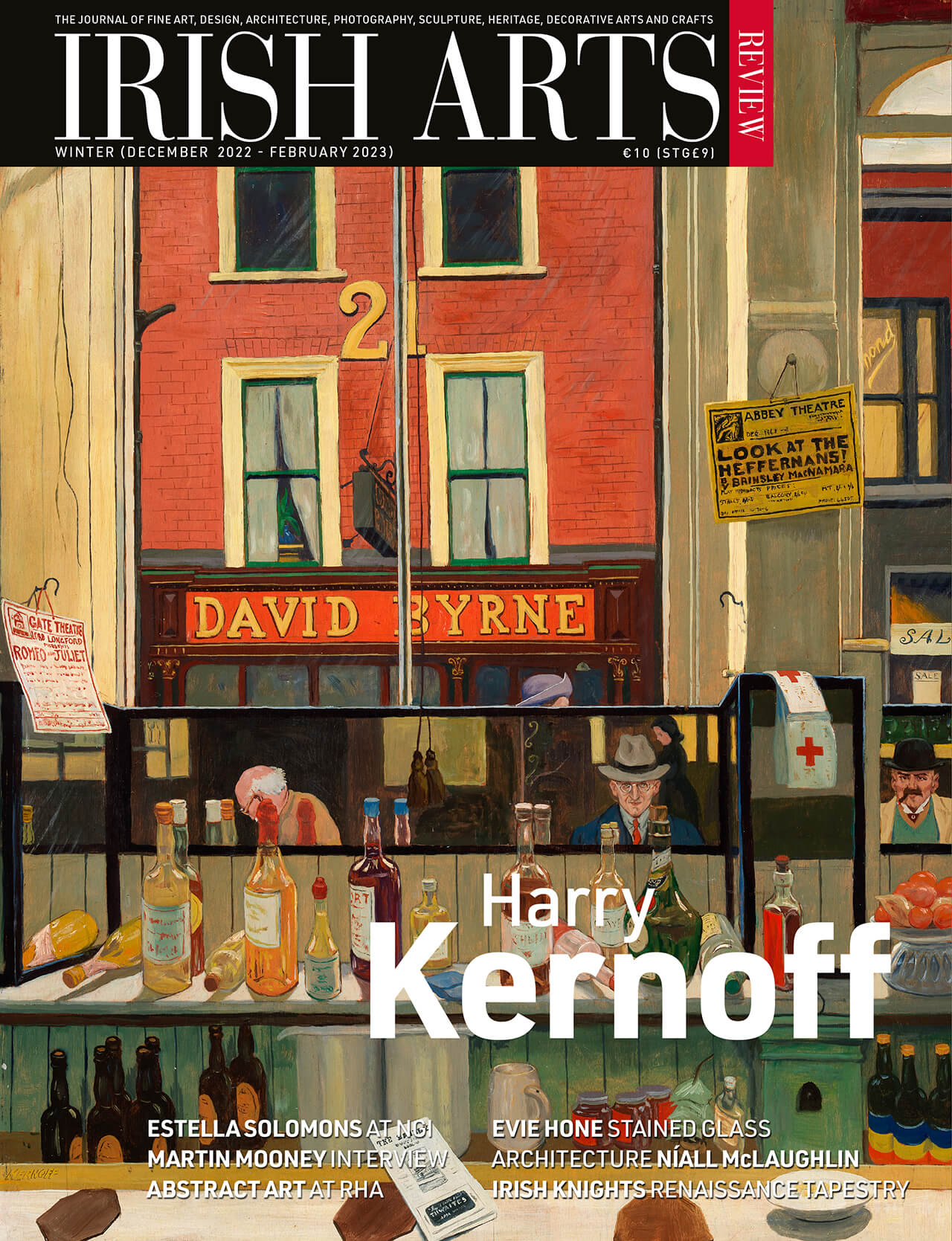

Brian Fallon remembers a modest exhibition that began a love affair with the work of Harry Kernof

Aidan Dunne talks to painter Martin Mooney about his career and the development of his work