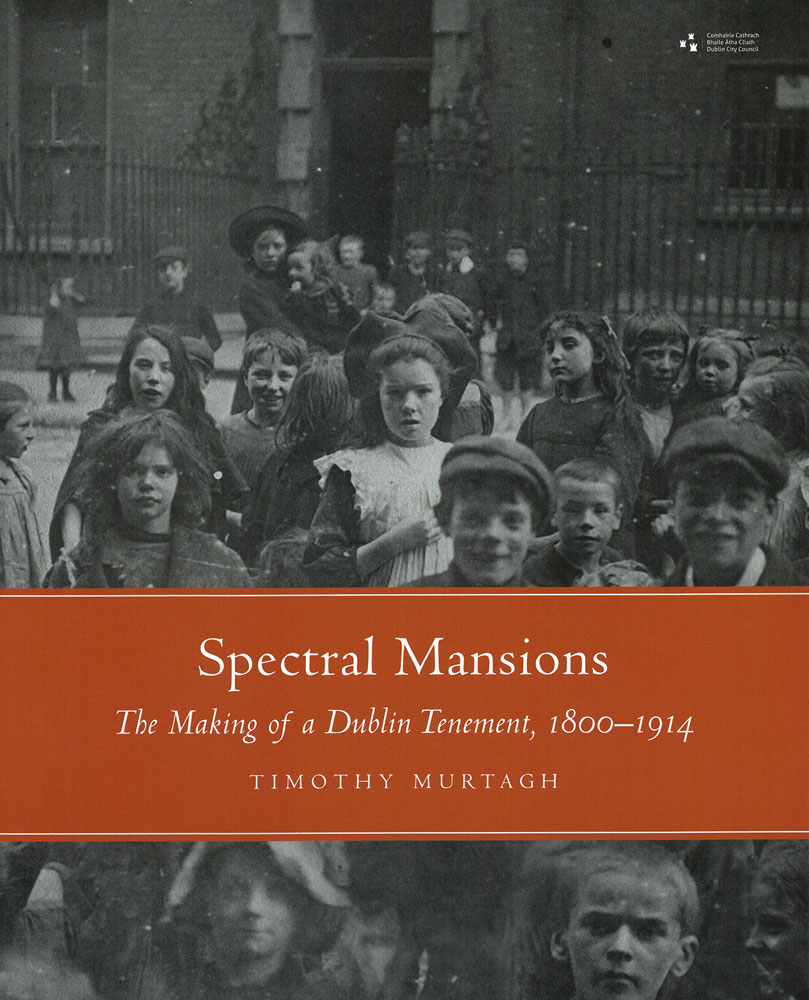

Timothy Murtagh

Four Courts Press, 2023

pp 264 illustrated h/b

€27 ISBN: 978-1-84682-867-6

Reviewed by Sinéad McCoole

This book begins with promise, documenting Henrietta Street as the political address in Dublin. Timothy Murtagh’s lively prose keeps the reader’s attention throughout, and it is remarkably consistent across the periods it covers, from 1800 to 1914. Charting how those who objected to the Act of Union protested that it would turn Dublin into ‘a sleepy backwater’, the author takes his time in recording alternative accounts.

Murtagh writes in an accessible way, using modern terms like ‘letting’, ‘subletting’, ‘speculators’, ‘markets’, ‘vision’ and ‘selling to the fashionable set’. While the stories of the ‘salubrious neighborhood’ are to be expected, the residents of the street were to this reader a welcome surprise. Murtagh describes how Mary Wollstonecraft’s book A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) was formed from her experiences as a governess in Dublin. There is a wide-ranging discourse on economic decline in the period from 1845 to the 1890s, alongside another story of the emerging transport hubs in proximity to Henrietta Street and its transformation to a centre of legal education. The establishment of the Encumbered Estates Court at 14 Henrietta Street made it an important address once again. In time, such was the demand for it, the court had to move to larger accommodation. That house was then taken over by a member of the militia following another period of rebellion against colonial rule. In 1867 the first tenements are listed on the street. ‘Better-class’ people, facilitated by the expansion of the railways, were moving out of the city, Murtagh charts this decline with sensitivity, his work with 14 Henrietta Street, now the Tenement Museum, at its centre. The section opens with a declaration that the tenements ‘remain invisible to the historian’. However, what emerges in the pages that follow, using an exhaustive range of source material, is the fullest account of them to date. ‘Dear, dirty Dublin’ is explained, the complexity of ownership contrasted with the conversion of houses for working-class occupancy as purpose-built tenements elsewhere. Henrietta Place, once the stable-yard of number 15, was inhabited and overcrowded in 1913, as shown by photographic evidence.

‘Better-class’ people, facilitated by the expansion of the railways, were moving out of the city, Murtagh charts this decline with sensitivity

From the start, the author’s use of literature adds an extra dimension to the book – for example, James Joyce’s description of dire poverty, ‘minute vermin-like life’, and Paula Meehan’s commissioned poem on 14 Henrietta Street. Her words ‘spectral hands throughout the ages’ inform the title of the book. Meehan conveys a range of experience through time in forty-one words, alongside the illustration from The Capuchin Annual (1940) entitled ‘A Tenement Nocturne’ by William H Conn. In this pen-and-ink drawing of a tenement room, a child, waking while another sleeps, sees the ghosts of a gentleman and lady in 18th-century attire, dancing.

Fully illustrated with a mix of maps, cartoons, drawings, theatre stills and material culture, (the author was assisted by Charles Duggan, Dublin City Council’s Heritage Officer), this work was years in the making. It is a massive work of scholarship to revisit again and again.

Sinéad McCoole is an historian, author and curator.

Aoife Ruane looks at artist Niamh McGuinne’s work, on show at the Highlanes Gallery

Pascal Ungerer’s peripheral landscapes evoke a sense of silence and isolation , writes Margarita Cappock

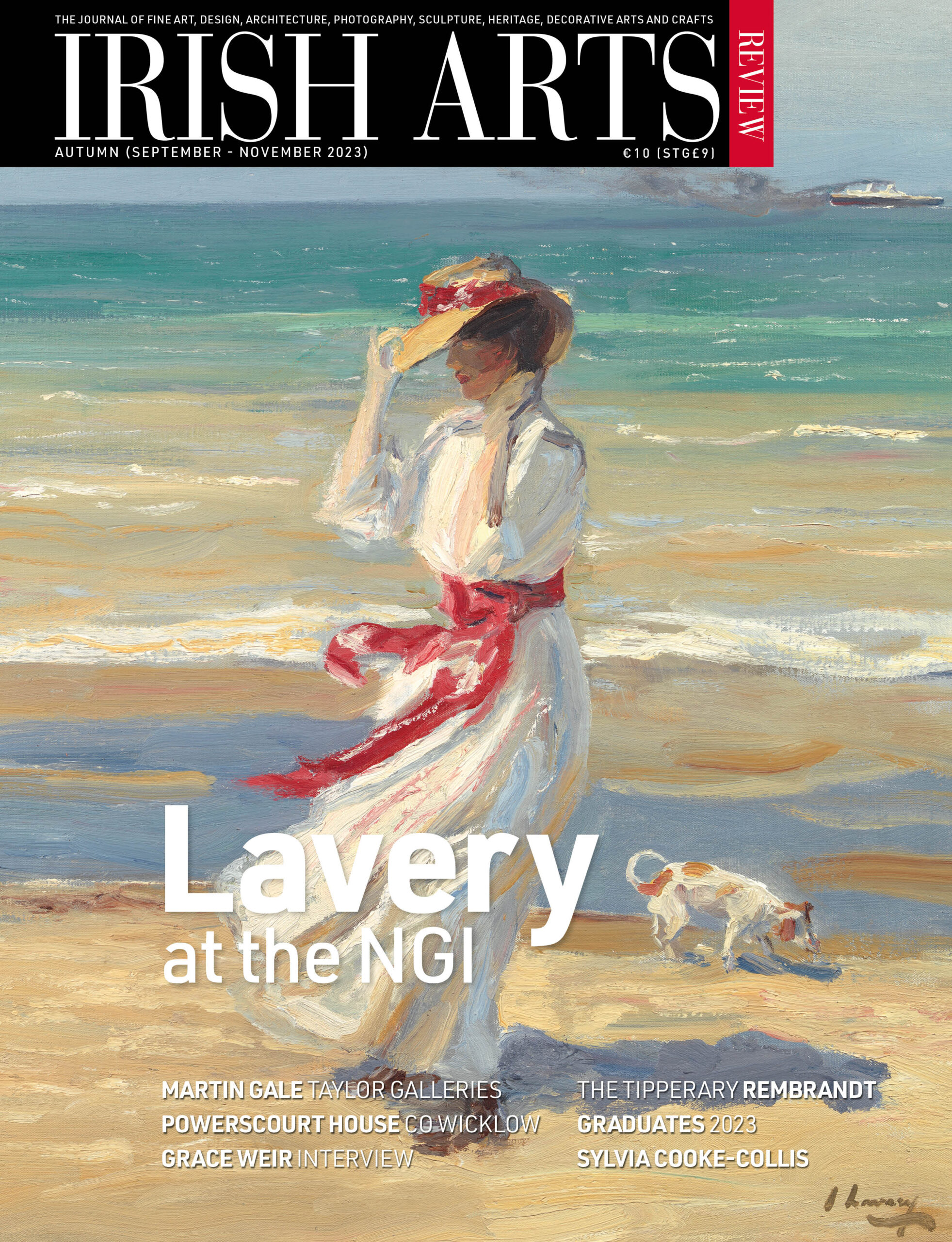

On the fiftieth anniversary of her death, Michael Waldron assesses the work of Cork artist Sylvia Cooke-Collis