Eoin Ó Broin & Mal Mccann

Eoin Ó Broin & Mal Mccann

Merrion Press, 2021

pp 224 fully illustrated hb

€35/ £30 ISBN 978-1-78537-418-0

Stephen Best

Busáras has always sparked public imagination. From the start, its design, scandalised by scale and cost, became a cause cél√®bre for the then-leading Irish politicians. This resulted in a ten-year delay, reams of competing newspaper commentary and erosion of vision. While dogged at home by petty political squabbles, opinions were very different internationally. The design, construction and political ideas behind it were celebrated by a world looking for a bright new future after the horrors of war.

The building, today, is a little careworn, with a faint whiff of tragedy around it. Taken for granted, the architecture is invisible to most Dubliners. Busáras has become a hoary ghost of unfulfilled potential; the interesting social spaces long since closed to the public and the once-vibrant polychrome exterior are crumbling and dulled by apathetic maintenance. Yet undoubtedly it remains Ireland’s most important Modernist building. Nothing else in the city matches its vision or execution, and those who use it love it.

Eoin √ì Broin’s book, with photography by Mal McCann, is a work of literary non-fiction that attempts to outline the life of Busáras, punctuating it with architectural detail and leavening it with digressions about everything from personal testimony, political intrigue and air conditioning to drag queen Panti Bliss.

It is not like other architecture books I have read. And that is a good thing. Ó Broin is not an architect, an academic or a writer, but a politician adept at writing. He joins some very disparate dots, skirting around the history of modern Ireland, its successes and failures.

Those who designed and supported Busáras demolished the stereotype at home and abroad of the censorious, protectionist, narrowly nationalist Free State

In particular, √ì Broin draws attention to the role Busáras played in symbolically pre-empting a shift from the isolated ‘austere republicanism of de Valera‚’, with its fairytale of economic self-sufficiency, to Keynesian common sense. Those who designed and supported Busáras demolished the stereotype at home and abroad of the censorious, protectionist, narrowly nationalist Free State.

Whereas the political, cultural and social readings are fluent and engaging, the chapters on architecture and design are more tentative and unsure, relying heavily on a small footprint of texts and one-to-one interviews. This is understandable and is not where the strength of the book lies.

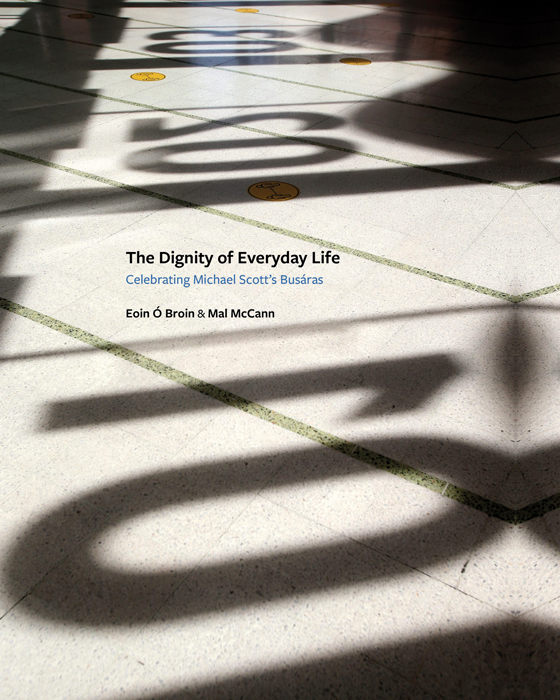

Mal McCann’s photographs play an important role in telling the story. There is a plain, everyday quality to them. Snapped from eye level, most are dim and lack the trained architectural photographer’s obsession with perspective correction. This unpolished style reinforces the idea that this is a building in desperate need of our love, care and attention.

The enigmatic cover photo of gorgeous terrazzo elegantly adorned with exquisite shadows – but also social-distancing stickers – encapsulates the notion of beauty among uncertainty. The Dignity of Everyday Life ends up resembling both a eulogy and a distress signal, but is never clearly either. Are we to wonder at its creation or worry about the future?

Stephen Best is a senior lecturer at the Dublin School of Architecture, TU Dublin.

Stephanie McBride explores Deirdre Brennan’s photographic response to James Joyce’s Ulysses

James Howley is impressed by Grafton Architects and O’Mahony Pike’s rebuild of the ESB headquarters and believes it is a building of international importance