In addition to creating a likeness of her daughter, Geraldine O’Neill has in mind the age-old interrogation of representation, writes Robert Ballagh of this year’s recipient of the Ireland-U.S. Council/Irish Arts Review Portraiture Award

Without question, for most of the 20th century, the painted portrait was judged by many as being almost irrelevant in terms of acceptable art practice, to the extent that its obituary was penned time and time again. With deliberate irony, Blake Morrison wrote, ‘First photography surpassed it, then modernism smashed it to pieces, then abstract expressionism rendered it meaningless and now installation and video art have finished it off.’ Yet the truth is that the death of the painted portrait has been greatly exaggerated. It has not only survived into the 21st century; on the contrary, it has flourished. Nevertheless, it must be admitted that the development of modern art in the early 20th century created a real challenge for the portrait painter, because, once modernism became established as a significant cultural force it quickly embraced a foundational ideology which, like all powerful belief systems, was not content to merely trumpet its own virtues but felt it necessary to demonize previously accepted concepts as heretical. For example, the depiction of a three-dimensional reality on a two-dimensional plane, the stock-in-trade of painters for centuries, was dismissed as hopelessly anachronistic and basically dishonest. Also the historic striving by artists to paint an accurate likeness of a fellow human being was viewed as an unnecessary and pointless exercise.

Obviously the dominance of such fundamentalism created a difficult working environment for the portrait painter during the rise of modernism but some brave souls persevered with the practice despite being relegated to a marginal position in the version of art history under construction. However, the renewed significance of the painted portrait in recent decades is due to something more fundamental than simply perseverance. Naturally a good portrait must fulfil its expected obligations, namely to resemble the sitter and to have been well painted, but a great portrait must go beyond those obvious requirements. It must exude an ‘aura’ a special quality eloquently described by Walter Benjamin in his treatise, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. This is where an exceptional work of art possesses a particular presence that transcends the sum of its constituent parts. This is something that no other means of representation can do.

Today, in this digital age, where so much is possible, a five-hundred-year-old technology, namely the normal application of oil paint to an appropriate substrate, can still achieve results that are both special and unique. With a painted portrait the viewer is not just presented with the outward appearance of the subject but through visual contact with the means of representation – the physical marks on the surface – a special relationship can develop between the viewer and the actual artist. Looking at Rembrandt’s later self-portraits, initially one marvels at the extraordinary representation of the trials and tribulations of the ageing process but closer examination of the painted surface reveals the skilful marks and gestures made by the painter himself. This intimate experience not only dissolves the centuries since its execution, but metaphorically speaking, places the viewer at the artist’s shoulder during the creation of the masterpiece. Looking at an art video or installation just doesn’t come close!

Today, in this digital age, where so much is possible, a five-hundred-year-old technology, namely the normal application of oil paint to an appropriate substrate, can still achieve results that are both special and unique

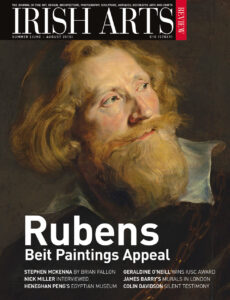

The re-integration of the painted portrait into the artistic mainstream in recent decades has been greatly assisted by the establishment of the National Portrait Awards in London and, here in Ireland, by the National Portrait Exhibition, sponsored by Arnotts department store and organized by artist Jacqueline Stanley and my late wife Betty Ballagh. Over the ten years of this exhibition many of today’s successful portrait painters received their initial support and encouragement. This tradition has been continued by the Irish Arts Review and the Ireland-U.S. Council who award a prize each year for the best portrait in the Royal Hibernian Academy’s Annual Exhibition. This year’s winner is a striking work by Geraldine O’Neill entitled, Drawing. Portraiture has always formed a part of Geraldine O’Neill’s practice as a painter, but not, however, in the conventional sense – no boardroom stuffed shirts for her! No, her sitters are far more informal and personal, often her own children. In fact, her winning portrait features her daughter Si√∫n, proudly displaying her own drawing, and it is this clever concept that, in turn, provides a key to the interpretation of what is quite a complex picture. It seems to me that apart from creating a likeness of her daughter, the artist has in mind the interrogation of representation itself: the question of how, over the centuries, artists have struggled to devise a satisfactory means of describing the world we inhabit. In Drawing Geraldine O’Neill places the child in front of her version of a Northern Renaissance landscape painting by Patinir, which surprisingly includes a Chernobyl-like nuclear reactor puffing out child-like clouds of smoke, or, more worryingly, poisonous radiation! She also superimposes a crude child-like drawing of a cube, perhaps suggesting that a child’s efforts in describing three-dimensional space echoes the historical struggle to master the laws of perspective. The monochrome nature of the picture, created in charcoal and conté crayon, provides an opportunity for the artist to use coloured oil pastels in order, by way of contrast, to emphasize complex concepts in the painting; however, perhaps most significant of all is the red heart, symbolizing love, reproduced in the child’s drawing. Geraldine O’Neill graduated from NCAD in 1993 and returned there to complete a Masters Degree in 2008. She was elected an associate of the RHA in 2012 and this year became a member of Aosdána.

The RHA 185th Annual Exhibition, RHA, Dublin until 9 August 2015.

Robert Ballagh is an artist and a member of Aosdána.