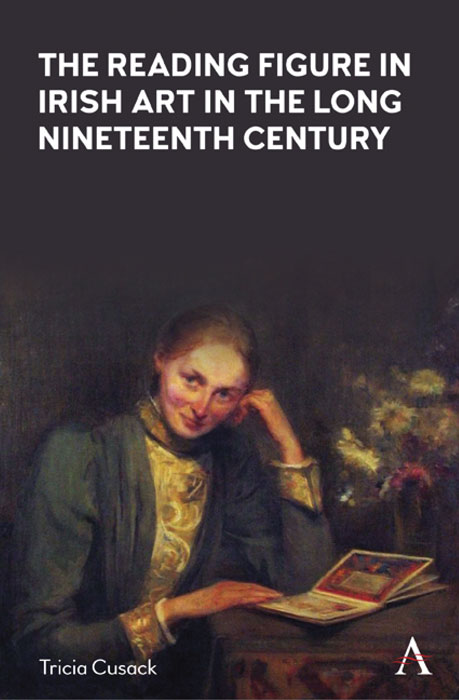

TRICIA CUSACK

Anthem Press, 2021

pp 250 illustrated h/b

£80 ISBN: 978-1-78527-644-6

Emer McGarry

This engaging and erudite volume fizzes with ideas and originality. The book opens with a description of the writer as a child in a school library, absorbed by George Eliot’s Silas Marner. This is the first of many images of a reading figure that we encounter throughout the volume. Such scenes, Cusack argues, do not merely depict a person that reads, but are ‘a concatenation of signs incorporating a host of historical and cultural references’.

This engaging and erudite volume fizzes with ideas and originality. The book opens with a description of the writer as a child in a school library, absorbed by George Eliot’s Silas Marner. This is the first of many images of a reading figure that we encounter throughout the volume. Such scenes, Cusack argues, do not merely depict a person that reads, but are ‘a concatenation of signs incorporating a host of historical and cultural references’.

The term ‘Irish art’ is applied broadly to the work of those whose lives were framed in some way by an experience of Irish culture and politics. The artists and sitters discussed are mainly Anglo-Irish, many of whom fostered radical ideas about the rights of women and Irish nationalism. The writer persuasively locates the depiction of reading figures in Irish art within a broader European tradition of similar subject matter that existed throughout the 19th century. Unlike their European counterparts, which placed the emphasis on the subjects’ physical appearance and dress, Irish and Anglo-Irish representations of readers developed alongside initiatives of greater social and political advancement for women and subtly propagated new ideas.

The writer persuasively locates the depiction of reading figures in Irish art within a broader European tradition of similar subject matter that existed throughout the 19th century

The volume explores portraits of reading figures in the long 19th century, defined as the period between the Act of Union in 1801 and the 1916 Rising. This was, Cusack argues, a particularly fertile time in Ireland. A rich visual-art scene existed in Dublin prior to the establishment of the Catholic state, ushered in by independence in 1922. This was also a time of enormous social and political change, which saw two particularly important shifts. One was the slow corrosion of Anglo-Irish power and the other was the beginning of a push for greater rights for women. These changes were accompanied by the construction of new gender identities, and Cusack compellingly argues that visual art played a subtle but important role in the establishment of both ‘Manly Nationalism’ and the ‘New Woman’.

Cusack provides a fascinating overview of the representation of masculinity in the Irish context and the way in which it absorbed elements of ‘Imperial Manhood’ to create the idea of ‘Muscular Catholicism’. Reading, especially of fiction, was incompatible with the ‘cult of manhood’. However, for privileged Anglo-Irish women, the availability of a greater amount of reading material opened up space for intellectual engagement and creativity away from the patriarchal gaze. This was reflected in depictions of women as serious, silent reading figures and contributed to the construction of the ‘New Woman’, who bicycled, smoked in public and wore rational dress.

Cusack’s engaging style makes light work of dense material, while never compromising on erudition, in a cohesive overview that integrates histories of literature and visual art. If there is one drawback to the edition, it is that Cusack’s richly compelling descriptions of the artworks themselves are let down by the quality of the images reproduced in the book. Although readers will be left yearning to see the works in full colour for themselves, this is a lively volume that will enrich even those with only a passing interest in the subject.

Emer McGarry is Director of The Model, Sligo

Unravelling the sequence of carving on the stones has been challenging but has been helped by the fact that there are so many examples to study, writes Elizabeth Shee Twohig