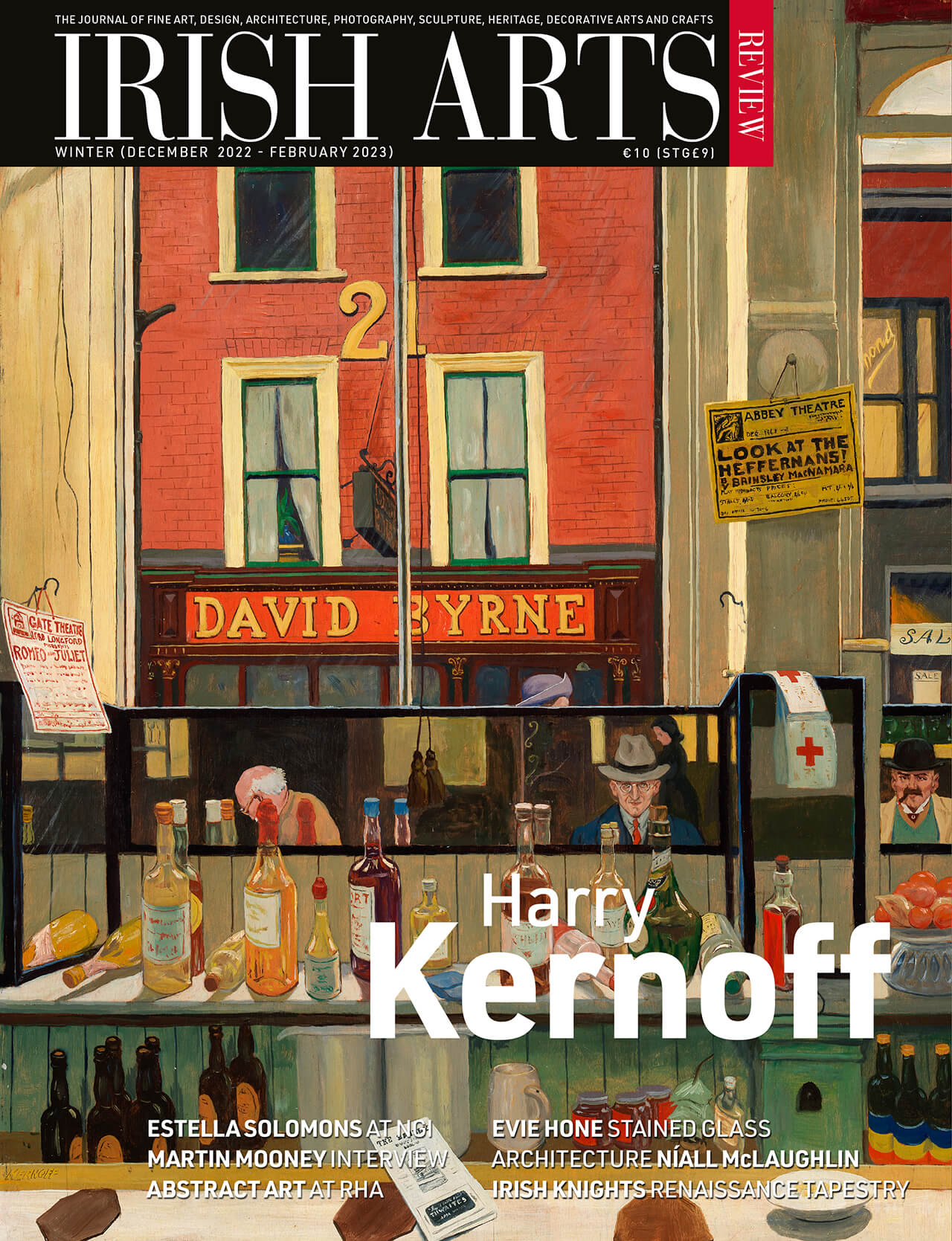

Brian Fallon remembers a modest exhibition that began a love affair with the work of Harry Kernof

Harry Aaron Kernoff (1900–1974)Silver Birches, Phoenix Park, Dublin 1933 watercolour 22.86 x 31.75cm

Brian Fallon remembers a modest exhibition that began a love affair with the work of Harry Kernoff

Harry Kernoff was an almost unavoidable figure in the Dublin of half a century ago. I knew him quite well then, but not intimately. He, in turn, seemed to know just about everybody, although he remained curiously private, perhaps even a little touchy and sad. No doubt he was fully conscious that he belonged to another era, the crucial years between two world wars. Kernoff was quiet, gentle and well mannered. He never forced himself into company unless encouraged and did not throw his opinions in other people’s faces. The Pearl Bar in Fleet Street was one of his beats and enough oldsters still drank there to make him feel at home.

He appeared to live on very little. Probably that little was earned via his woodcuts, of which he produced three books. I can see in memory his small face under a black hat, which was rarely taken off, his glasses and his serious look. On a number of occasions, as I stood with friends and colleagues at some bar or other, I insisted on buying him a glass of Guinness – which he duly drank, but plainly could not reciprocate. Instead, just before he left, he reached into his coat pocket and fished out a black-and-white postcard reproduction of a Dublin drinking scene – one of his most familiar woodcuts, entitled A Bird Never Flew on One Wing. Over the years I came to own a dozen like it.

To read this article in full, subscribe or buy this edition of the Irish Arts Review

Harry Kernoff was an almost unavoidable figure in the Dublin of half a century ago. I knew him quite well then, but not intimately. He, in turn, seemed to know just about everybody, although he remained curiously private, perhaps even a little touchy and sad. No doubt he was fully conscious that he belonged to another era, the crucial years between two world wars. Kernoff was quiet, gentle and well mannered. He never forced himself into company unless encouraged and did not throw his opinions in other people’s faces. The Pearl Bar in Fleet Street was one of his beats and enough oldsters still drank there to make him feel at home.

Joseph McBrinn charts the history of Evie Hone’s Tullabeg windows, which illustrate scenes from the life of Christ

Síghle Bhreathnach-Lynch remembers a leading member of the Celtic Revival, artist Mia Cranwill

Aidan Dunne talks to painter Martin Mooney about his career and the development of his work