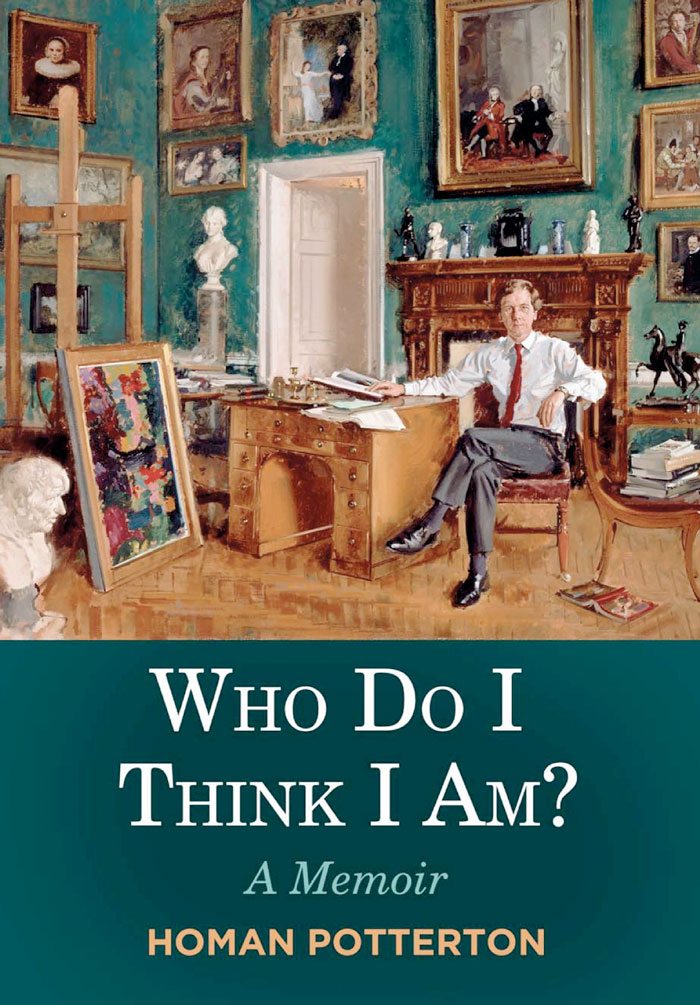

Homan Potterton Merrion Press, 2017 pp 300, col ills 10, b/w ills10 h/b €24.99 ISBN: 9781785371509 Reviewed by Peter Somerville-Large The title of Homan Potterton’s memoir derives from a poem by Paul Durcan who described him as ‘the new young dynamic whizz-kid Director’. This sequel to Rathcormick, Potterton’s engaging account of his childhood, brings together his life in the art world of London and Dublin. The farmer’s son from County Meath attended Trinity College in the 1960s, where the lectures of Anne Crookshank on the history of art encouraged him towards his chosen career. He worked for two years at the National Gallery of Ireland, making many friends in the Dublin art world whom he lists in a diary he kept in 1973 which reads like a social gazetteer of important names. In 1974 he obtained the post of Assistant Keeper at the National Gallery in London. ‘I felt that the job was not at all my field and I knew next to nothing about old master pictures.‚’ However, his diffidence was disproved and he spent six enjoyable and successful years at the post. James White, the long-time Director of the NGI, noted his achievements and proposed him as his successor. Potterton was very young. ‘Thirty-three, the same age as Jesus Christ!’ White remarked. ‘And look what happened to him,‚’ Potterton countered. After he had arranged a big exhibition of 17th-century Venetian paintings in London, Ireland still beckoned. He came to Dublin reluctantly where he was elected to the position of eleventh and youngest Director of the NGI. He took up office in June, 1980. From the start Potterton found that his position offered major pitfalls. These included staff dissatisfaction: he lacked White’s tact and patience; confrontations with unions, government cuts, the shabby state of the Gallery buildings, outdated electrical wiring, filthy wall coverings and telephones that didn’t work. There was very little money for the Gallery upkeep, and with water dripping from its roof, the fabric needed a substantial overhaul which was not forthcoming. He had a thorny relationship with Charles Haughey who considered him ‘the little County Meath brat.’ He was taxed on his salary at sixty-seven per cent.

Homan Potterton Merrion Press, 2017 pp 300, col ills 10, b/w ills10 h/b €24.99 ISBN: 9781785371509 Reviewed by Peter Somerville-Large The title of Homan Potterton’s memoir derives from a poem by Paul Durcan who described him as ‘the new young dynamic whizz-kid Director’. This sequel to Rathcormick, Potterton’s engaging account of his childhood, brings together his life in the art world of London and Dublin. The farmer’s son from County Meath attended Trinity College in the 1960s, where the lectures of Anne Crookshank on the history of art encouraged him towards his chosen career. He worked for two years at the National Gallery of Ireland, making many friends in the Dublin art world whom he lists in a diary he kept in 1973 which reads like a social gazetteer of important names. In 1974 he obtained the post of Assistant Keeper at the National Gallery in London. ‘I felt that the job was not at all my field and I knew next to nothing about old master pictures.‚’ However, his diffidence was disproved and he spent six enjoyable and successful years at the post. James White, the long-time Director of the NGI, noted his achievements and proposed him as his successor. Potterton was very young. ‘Thirty-three, the same age as Jesus Christ!’ White remarked. ‘And look what happened to him,‚’ Potterton countered. After he had arranged a big exhibition of 17th-century Venetian paintings in London, Ireland still beckoned. He came to Dublin reluctantly where he was elected to the position of eleventh and youngest Director of the NGI. He took up office in June, 1980. From the start Potterton found that his position offered major pitfalls. These included staff dissatisfaction: he lacked White’s tact and patience; confrontations with unions, government cuts, the shabby state of the Gallery buildings, outdated electrical wiring, filthy wall coverings and telephones that didn’t work. There was very little money for the Gallery upkeep, and with water dripping from its roof, the fabric needed a substantial overhaul which was not forthcoming. He had a thorny relationship with Charles Haughey who considered him ‘the little County Meath brat.’ He was taxed on his salary at sixty-seven per cent.

His major triumph as Director was the acquisition of the Beit paintings. That we have a Vermeer and a Velázquez is largely due to his capacity for friendship; he had met the Beits in London

On the positive side Potterton set about the important task of arranging the cataloguing of the Gallery pictures which, amazingly, had never been done properly. With money from the George Bernard Shaw fund he purchased a number of significant continental paintings. He bought and refurbished No 90 Merrion Square, an important neighbouring addition to the Gallery. The Board of the Gallery which included Bill Finlay, was ‘unanimously and unequivocally supportive and agreeable to every thing I asked.’ His major triumph as Director was the acquisition of the Beit paintings. That we have a Vermeer and a Velázquez is largely due to his capacity for friendship; he had met the Beits in London. His account of his role in the second robbery at Russborough reads like a John le Carré thriller. When the Beit paintings were formerly handed over to the Gallery, a number were still in the hands of thieves, and were not recovered until 1994, long after his departure from Dublin. I was shown Goya’s battered Do√±a Antonia Zárate which had been rolled up, exposed to damp, had lost sections of its paint, and its sides were slashed when it was cut off its stretcher. Alas, in 1988 Potterton decided he had had enough of the impoverished and dilapidated National Gallery of Ireland and resigned his directorship. Almost immediately afterwards the Department of Finance allocated more than IR £5 million for the first phase of the Gallery’s refurbishment. Peter Somerville-Large is a novelist and travel writer.