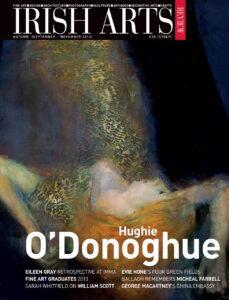

‘Culture is about sharing; Nationalism is about ownership.’ Hughie O’Donoghue encapsulates the chasm between the two concepts, in conversation with Brian McAvera

Brian McAvera: Your father was born in Manchester, of Irish stock; your mother was Irish and emigrated in 1937, and your grandfather emigrated to England in 1911. Family holidays were regularly spent in Mayo in the 1950s and 1960s. You are British and so described in most of the catalogues, but what do you consider your identity to be?

Hughie O’Donoghue: I’ve never had any ambiguity about that. My origins are Manchester/Irish. I am English by birth but grew up steeped in Irish culture. I feel that I have had a strong sense of origins. The family originated in Ireland and I think that that was deliberately passed on to me by my parents. Looking at the photographic records, some of my father’s photographs are knowing, for the time, and I am placed in the landscape of Mayo rather than Manchester. My father was a very intelligent man, and my mother also wanted to make me aware of my heritage and background. There’s also my own free will. In 1995 we moved to Ireland, house and studio. It was my conscious decision to do that. I’ve always been focused on what I would see as cultural rather than national identity. Culture is about sharing; Nationalism is about ownership.

There are very few people now who are only of one place. We’re all in this modern cultural world now. A lot of my work has been a probing of what identity means: our ideas of who we are. In Ireland I discovered that many people form opinions about your identity based simply on your accent, which I find quite amusing for a nation that sent its people all over the world.

BMcA: Your father was conscripted into the English Army in 1939, was at the Fall of France in 1940, Southern Italy in 1944, and Greece in 1945. Like hundreds of thousands of servicemen his life must have been radically changed. What was it like for yourself, and your mother, growing up with an ex-army veteran? How influential was he on your journey as an artist?

H O’D: I’ve thought a lot about this, particularly since he died. I’ve pored over his letters sent during the War. I think he was very damaged by it. I’ve gone into it almost forensically. As recently as last year a certain penny dropped. It occurred to me that he had probably killed a lot of people. He was a platoon sergeant in Italy and in his letters you get a sense of him losing his nerve, gradually. He was taken out of the front line in Italy in late 1944 and sent to Athens. His corporal was shot next to him in a square in Athens by a woman who concealed a gun in a pram as she approached them. He was only twenty-seven when he came back. You could see the experience etched on his face. I think it made him a troubled man. It wasn’t the only thing, the only burden he carried. There is a legacy from his own childhood. He was the eldest boy and was sent back to Ireland, to Kerry in 1920, when he was only two, and we know what was going on in Kerry in the 1920s! His entire primary education was there. The facts of that are that he lost his real mother when he was two by being sent back to Kerry, and then again when he was ten because he had become very attached to his aunt. He wasn’t an easy man to live with. He won a scholarship to Manchester Grammar School, which was Protestant but he wasn’t allowed to take it up. I think he felt frustrated and the books were an escape and a way of educating himself. His younger brothers both became headmasters but he worked as a railway clerk.

That contrast Between the urban environment and the wild west of Co Mayo helped form my imaginative world

In the simplest way he took me to Manchester Art Gallery, to museums and art galleries, and communicated that it was important. That was unusual. I didn’t know any friends in Manchester whose parents took them regularly to art galleries. That influenced me. The library influenced me. You could look at the library and think of it as a dark enclosing space with the dark red spines of the Everyman Library books. To me it seemed a vast space of potential knowledge. I’d look at the pictures in the books. They left me with a sense of excitement. They represented possibilities: all these stories and undiscovered avenues of experiences. The memory of the books has found its way into my work and I have made a number of paintings where I have used books as the ground. The most recent is a new painting I made for the new library building at NUI Maynooth Red Books (Fig 1). It’s made on twenty-seven opened books and the theme is enlightenment. So that was how he influenced me and in later years we did talk about painting and he would have his favourite artists – not necessarily mine!

BMcA: You were born in 1953 in Manchester, home to the Whitworth Art Gallery and Manchester City Art Gallery, a city with strong literary, artistic and theatrical traditions. How far are the roots of your painting embedded in your childhood experiences?

H O’D: I think we experience things more vividly when we are young. That has been a motif in my work for as long as I can remember. So memory is a constant touchstone and my memories of growing up in Manchester are vivid. In the first instance I grew up in a council house in Wythenshaw which is, some say, the largest housing estate in Europe. In the house I grew up in, every wall, with the exception of the kitchen, was covered in books. It was unusual and my father, like a lot of Irish people – he would certainly have seen himself as Irish even though he was born in Manchester – was fixated on education as a kind of pathway out of poverty. That experience was etched in him from his own childhood in Manchester. So it was particular, but it was also affected by being taken back to Ireland every year in the summer. That contrast between the urban environment and the wild west of Co Mayo helped form my imaginative world. The annual journey there was greatly anticipated. It represented a free environment and in the early days you took your shoes off when you arrived and six weeks later you put them on. You went native: the feel of grass on your feet. Elemental things affected me. That has seeped into my work‚Ķthe cutting of peat for the fire, getting water from the river for drinking or washing. This was from 1953, throughout the late 1950s to the early 1960s, and it’s hard to believe how simply people lived then. We absolutely loved it. The dangers we were constantly warned about, like drowning in a lake, were very different to those of Manchester. We all went mad on fishing the Glencullen River and the Glenturk to a lesser extent. My father encouraged that. I took from it not so much an interest in fishing but an interest in following the river as it meandered and cut into the bog. I was focused on catching trout but what I took was a sense of the natural beauty of the river, the form of the river, the meandering S shape recurs in the pictures. One of the things that’s interesting is that it’s only retrospectively that I’m able to say that.

BMcA: I suspect that the works of art we encounter when we are young or in early adulthood are formative. What did you encounter?

H O’D: I remember that series you talked about, ‘The Masters’, in school. Occasionally people at school would make copies. A pivotal moment was when I went down to London in 1968 to see the Manchester United/Benefica European Cup Final. I got down in early morning and spent the day wandering around London not knowing what to do. A while later I thought that I could have gone to the National Gallery! I started A Level Art in September 1969. Previously I was good at drawing. Now I started looking and was immediately excited. I urgently wanted to see the reproductions in the flesh and I started copying paintings: Cézanne’s Card Players, Rembrandt’s Woman Bathing in a Stream. I actually made a lot of oil sketches of Rembrandt’s paintings. The corporality attracted me. I was quite shocked when I actually saw them to see that they weren’t as densely painted as I had imagined. That was the moment I got excited about painting. I wanted to paint on canvas, was excited by the mechanisms. There was a painting on loan to Manchester City Art Gallery, Van Gogh’s Peach Trees in Blossom done in April 1888. He made the blossom from these dollops of paint and that – being able to see the texture – was a moment of revelation, that the actual painting was so much more interesting than the reproduction; seeing the paint itself rather than the image, so I started going to art galleries and eventually got to the National on my nineteenth birthday. There was also the fact that it was immediately apparent that I was good at painting as I was not constantly reprimanded at school as I was for not getting my maths correct! That feeds into your self-esteem.

But I didn’t go to art school because in those days you had to do a Foundation Course and stay at home. I wanted to get away from home, to get out into the world, so I went to teacher training college and had a whale of a time for three years. I didn’t even opt to do art there. But I was painting all the time, obsessively, so I eventually transferred to the Art Department. I never had any sense that I would be a painter: I just wanted to make paintings. I’d been told in Careers’ Advice to forget painting, that it wasn’t a serious option.

BMcA: You did an M.A. at Goldsmith’s in London (1980-82), showing in-between times in galleries in Leeds and Hull. How big a change was Goldsmith’s and how useful was it for you?

H O’D: I was a full-time secondary school teacher for six years while still doing my painting. I got a studio in an old co-op shop, on the top floor, in Goole. I submitted to send-in shows like the one at Hull and when I went to collect my painting the curator there, Lesley Dunne, asked to come out and visit my studio and I got a solo show. Shortly after that Leeds Poly gave me a show. I was beginning to think that perhaps I could be an artist but I had a job and a child and it was Clare who really drove the idea and encouraged me to go to London and to do the M.A. A transitional moment. Goldsmith’s was a mysterious exotic possibility but I was hugely disappointed when I got there. Hardly anyone was painting. There were long discussions about esoteric ideas, theories about modernism and I immediately found it very disappointing but it intellectually toughened me up in terms of being able to articulate what I was doing. Jon Thompson who was teaching the M.A. course had a brilliant mind. He was constantly probing lazy thinking. I realized that I had accepted a lot of idioms that were purely stylistic. I was a kind of formalist painter. At the end of the first year I realized that I had to reinvent who I was as an artist.

I did it in Brittany over a summer. Our first holidays in eight years. I abandoned being a formalist painter and decided to be a representational painter and found my first subject, the megaliths in Brittany. During the course of the following year I made a real transition, expressionistic painting of something rather than being something. There was excitement in the air. A return to painting. In 1980 I saw Baselitz’s Model for a Sculpture at the Whitechapel which came directly from the Venice Biennale along with four big lino cuts, all of which were figurative. I could immediately see their formal power and they influenced me. There was also a new spirit in painting, but I wasn’t interested in Bad Painting or in ironic painting such as the Italian pseudo Neo-Classical stuff. I was interested in authentic hard-won painting. It was dawning on me that there could be no such thing as conceptual painting (and me in Goldsmith’s!).

BMcA: In an interview in the Irish Arts Review in 1985 Sandra Miller pointed out that you began your career as an abstract artist. You noted that for many of your generation abstraction was ‘the established order’, citing American Abstract Expressionism and Post-Painterly Abstraction. You said that you wanted to ‘introduce figuration without losing any of the qualities’ that you ‘thought worthwhile in abstract painting’. What were those qualities, and would you still adhere to the credo?

HO’D: Probably yes actually! I think that the one thing that has characterized my work has been the idea that some kind of transformation can be wrought on this material, paint which has never been just colour thrown on the canvas. It’s the medium I’ve always been drawn to and I’m drawn to painters who can exploit the medium in a way unique to them. Terms like abstraction and figuration can be simplistic. All painting is an abstraction in a way. What I’m seeking to achieve is an equivalent for something felt; something that embodies rather than illustrates meanings. Meaning in art is a product. Illumination is a product of switching on a light switch. You have to surrender to the process of painting and I’m trying to achieve a tension between what is being represented and how it is represented.

BMcA: You’ve worked your way through a series of galleries: the Ferens in Hull (1979), and in London the Air Gallery (1984), Fabian Carlsson (1986) Purdy Hicks (1997) James Hyman (2008) and recently, crowning them all, the Marlborough Gallery, home to Bacon, Rothko and scandal. How far was this an organized career path, and what did these galleries give you?

H O’D: First of all, it was certainly not organized! I’ve always been shy and it was almost happenstance that things happened. At Hull, as I’ve said, the curator approached me, and one thing led to another. I’d made an application for the National Gallery but in relation to the first commercial gallery – I was at the opening of Fabian Carlsson’s gallery, and Stephen Cox introduced me to Fabian who was outrageously larger than life. I didn’t know how to deal with him. We went to the National Gallery where I had all my work stored, he bought all of it, then said ‘Let’s go to Paris in the morning’! He had real vision and wanted to do things big. He kind of burnt himself out. He got bored easily. So he closed the gallery, and then I worked with a number of different galleries and when I decided to leave England for Ireland I felt that I needed a gallery to represent my work in England. I was very good friends with Rebecca Hicks, still am, I had a long working relationship with Purdy Hicks and have the utmost respect for them. They gave me a lot of freedom, especially with publications as I was beginning to write in parallel to my work. Sometimes you’ve just got to change, you need a new challenge and that was the case when I moved on. I was looking for something new and I had known James Hyman for many years (he had come to me as a student) but it didn’t really work out. The gallery space and the context weren’t right for me. He was intending to move from Modern British to Contemporary but it didn’t happen. I gave it three years but it didn’t feel right so I looked around, already knew the Marlborough and asked them if they would be interested. They said they were, so I moved. It was not a planned self-promotion.

BMcA: With the ‘Earth’ series (amongst others) with its memories of Danish archaeological excavations of the Tollund Man, or the ‘Crow’ series, one tends to think of poets like Seamus Heaney and Ted Hughes respectively. Are you interested in poetry?

HO’D: I am. I came to poetry late. I never understood what it was earlier on. I think there’s a direct connection with Seamus’ poems in some of the early paintings though at the time I wasn’t aware of them. I had in my studio in the National Gallery reproductions of images from P V Glob’s book The Bog People. All those classical images in the National Gallery and yet there was something very Northern about the Tollund Man. My interest in poetry developed slowly. I remember reading Seamus’ poems. I could empathize with their themes – I wanted to make a kind of concrete poetry; the way words give you resonance by how they are placed. That’s increasingly interesting to me. The ‘Crow’ images: I would have been aware of Ted Hughes’ poems without having read them thoroughly. I’d tried to reintroduce subject matter into painting so that you can latch onto something that’s graspable. I’d see my painting as trying to make something that is poetic; something that is more than the sum of its parts.

The ‘Crow’ pictures came about when I was in the North, crossing the border, and came across a raven in the middle of the road on a foggy day (Fig 4). I went to a taxidermist and got a few stuffed ravens and had them in the studio.

BMcA: You’ve tended, until recently, to use a relatively sombre and restricted palette. Why?

HO’D: I talk about myself as a tonal painter. Rembrandt was really drawn to that. Something of that is a product of living in the British Isles where the effects of aerial perspective – shifting light – you get it in Turner, become distinctive for British and Irish artists. More recently my focus has shifted towards colour. I’m constantly circling to use striking colour in my current preoccupations. There’s been a shift from transparencies and glazing to opaque contrasts in colour. We change as we grow older but you’re absolutely right. Originally I was very focused on tonality and depth which is at odds with the majority of 20th-century painting. Perhaps I spent too much time looking at Rembrandt!

B McA: You have a tendency to work big – one thinks of Kiefer and Baselitz as well as of Tintoretto. As Robert Hughes often observed, scale has to be earned and many a modern painter expands a small-scale work into portentousness. Do you think you avoid this?

HO’D: When I was younger I was excited by doing things big. I think for a long time I tried to make large paintings without success. What was pivotal for me was the ‘Passion’ series which was exhibited at the RHA. Written into the contract were quite specific ideas about scale because they were modelled to some extent on the Tintorettos in the Scuola San Rocco, so I took that on and wrestled with it. It’s hard to judge what is successful or not but I feel that Three Studies for a Crucifixion, and the Blue Crucifixion, are successful. They were more than ten years in the making.

Increasingly I’m preoccupied with scale rather than size. One of the ingredients that seems very important is that the figure is never diminished in size. It’s all at human scale or bigger and because of the subject matter it seems to warrant that scale – that was what it was inviting you to reference. Also there’s an environment of colour wrapped around the viewer. It does have to be hard-won. Those big canvases were all stretched by me. That in itself is a labour of some magnitude. The size and scale should be appropriate to what the painting is about.

BMcA: You’ve been a printmaker since the start of your career, and likewise have produced dark brooding drawings – I’m thinking of Olive Tree II (1987) or Acqueduct with Graphite Cloud (also 1987) or The Round Lake II (1991). What is the relationship of the drawings and the (often) mixed-media prints to your painting?

HO’D: Drawings are a sporadic activity which I’m returning to, usually when I want to move forward or explicitly investigate something. They are more direct than the paintings. I’ve changed over the years. In the early days I was trying to make them the equivalent of the paintings, even in scale. I’ve tried to be technically innovative, drawing on canvas, doing large-scale drawings on collaged ground, and the most extraordinary drawings are the enormous watercolours with graphite dust which are both delicate and monumental.

When I begin a body of drawings I change something about how I work: putting an obstacle in my path. You’re stretching your abilities. It requires absolute concentration. More recent drawings are smaller in scale but not in ambition.

Regarding printmaking, I was dragged kicking and screaming into it in Italy in 1985. Since then I’ve always worked with printers. The early prints were on a different scale to the paintings. They were like miniature scale versions of paintings. In 1995, after being encouraged to work in carborundum for many years – I’d always been shown it as a textural effect – I found a way of making it behave like paint in a medium. I particularly like its painterliness but it’s also possible to make the plates in my studio as opposed to a print studio. I’ve been able to use printmaking to open up new areas. In recent years the prints have been made first and the paintings followed in terms of opening up my subject matter and in making technical progress. The ‘Line of Retreat’ prints – the first work about my father’s World War II experience — consisted of ten prints; ten different titles. That led into a series of paintings. Technically they signalled a new coloration, a new freedom of colour in my paintings. There’s something decisive in printmaking. You have to make a decision, and this can lead you to do something you have never done before.

BMcA: El Greco, one of the great outriders of art history, has fascinated a number of contemporary artists including the Irish painter Patrick Pye who even wrote a book on him. Both of you have produced various versions of View of Toledo. What’s the attraction?

HO’D: At the National Gallery in 1985 one of the keepers came down and told me that they were unloading a painting from the Metropolitan, the View of Toledo. Visceral painting! It’s very difficult to think of another early Spanish landscape painting. The View of Toledo is otherworldly yet strangely modern. It reminded me of Murnau’s film Nosferatu. The buildings seemed to have a personality. I was in the business of looking at paintings and so made some large-scale drawings of it – a translation of the work. It drew me in deeper. I’m particularly interested in his Laocoon as well; how he uses Toledo as a backdrop. The imagery of Cassino reminded me of El Greco’s View of Toledo. How God would see the world! He’s making the whole of the surface of the painting work in a rhythm. He’s very modern, very contemporary.

BMcA: Tell us about your Galway windows.

HO’D: It was my first time working with glass. The architects were doing a chapel and knew of my work. Hugh Kelly was keen to do a curved glass window (see IAR Autumn 2006, p.116). We went to Barcelona to look at a factory of a company called Cricursa. I made a painting, a painted design which was then photographed in high resolution and printed and encased in the glass. I was recently asked to make two large, new, stained glass windows for the Henry VII, Lady Chapel at Westminster Abbey in London. This was a very different task but in some ways one that was easier as so much about this ancient space was already there. I used predominantly blue and white glass which was etched, stained and enamelled to create a brilliance of colour and light and return the chapel to what I imagined it might have originally been like. I chose to work with very traditional methods and materials but to make something that was new and of the here and now.

BMcA: In a work like Monument to Rouen (2003) which incorporates photographic imagery you seem, like Mick O’Dea and his civil war paintings, to be providing in some senses a revisionist look at wars. Are you brooding on war in generic terms?

HO’D: I think that my subject is the fleeting and allusive quality of memory. The title comes from fragments I had to reconstruct. I knew that my father had ridden his motorcycle into a monument in Rouen and wrote it off and that he had been given a new motorcycle. Monuments are about remembering. The themes are about personal loss. Your father dies and is slowly disappearing. I suppose something dies when it’s not remembered. It’s a great metaphor as history gives you a particular version of the past which is not necessarily any truer than the poetic version.

Brian McAvera is an art critic.

From the IAR Archive

First published in the Irish Arts Review Vol 30, No 3, 2013