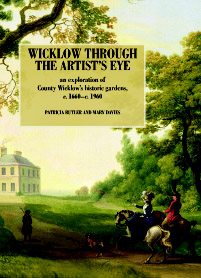

Wordwell, 2014

pp 360 fully illustrated h/b

€40.00 ISBN: 978-1-905569-82-3

Seamus O’Brien

Not for nothing is Wicklow called ‘the Garden of Ireland‚’. With a romantic landscape of rugged glens, babbling brooks, heather-clad mountainsides and a wonderfully indented coastline, Wicklow has captured the imagination of travellers, artists and garden enthusiasts for several centuries.

Given its proximity to the capital, the county has long been a playground for Ireland’s elite, and, over the past several hundred years, the Irish aristocracy and gentry happily settled here, creating magnificent country seats, surrounded by great gardens and extensive demesnes. During the 17th to 19th centuries, topographical artists discovered an inspiring landscape, and, with the aid of brush and pen, left a fascinating record of grand country seats, well-wooded demesnes, and now almost-forgotten beauty spots like the once popular Dargle Glen or demesnes that have long since disappeared like Blessington Park and Bellevue.

In producing this book, authors Patricia Butler and Mary Davies set out to explore over twenty of Wicklow’s most important estates and gardens from two points of view; those of the early travellers who left detailed descriptions and of the many artists who painted them. These range from from well-known professional Irish painters to keen amateurs, working in oil and watercolours, to rapid ‘on the spot‚’ sketches. Period photographs also supplement this imagery of a now long vanished period of grandiose living.

The authors have drawn from the vast repositories of written descriptions of early travellers as well as those of visiting artists. This must have been an enormous undertaking and the result is a wonderfully illustrated volume of great originality, featuring evocative topographical drawings and picturesque scenes, many of which have never been previously published. It paints an accurate picture of the lives of Wicklow’s grandees during the period 1660 to 1960, though mainly before the fragmentation of the larger estates by the Land Acts of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

A poet in words as well as in paint, he said that it was difficult sometimes to know ‘where reality begins and reflection ends‚’

One of Wicklow’s best-known demesnes is Killruddery, which has been connected with the Brabazon family, since 1544, when the suppressed monastery of Thomas Court in Dublin was granted to William Brabazon by Henry VIII. Sir William’s son, Edward was then granted the lands of Killruddery in 1618. It was Edward’s grandson William, the ist Earl of Meath, who began to lay out the present estate. Killruddery, the oldest surviving Dutch-style garden in Britain and Ireland, also has the distinction of being one of the earliest Irish gardens designed in the baroque French fashion closely associated with 17th-century landscape architect André Le N√¥tre, principal gardener for Louis XIV of France.

As one would expect from such an important country seat, there is a rich and extensive artistic record of the Meath Estate including Thomas Sautelle Roberts‚’, RHA (1760-1826), Killruddery from the South, c.1802. This panoramic view of the demesne from Windgates provides a picturesque rural scene of a heavily wooded estate flooded in the golden light of dawn, with smoke rising from the chimney stacks of Lord Meath’s manor house deep in the valley beneath, as sheep quietly graze near his tenants thatched cottages in the foreground.

It is perhaps the painting The Killruddery Hunt (Anon) c. 1740-50, that best depicts the early garden, with features that visitors today would recognise – the twin canals with the double lime avenue extending beyond and Killruddery’s most beautiful garden area ‘the angles‚’. The latter feature, a classic from the school of 17th-century French design, consists of trimmed lime, beech, hornbeam and yew hedges, flanking avenues that radiate out from a circle and is known quite simply as patte d’oie or goose foot. The painting was later enhanced (c. 1820) with figures of riders and hounds giving chase through the park and across the little Little Sugar Loaf.

The authors have drawn from the vast repositories of written descriptions of early travellers as well as those of visiting artists

The 6th Earl succeeded to the title in 1715 and was an extremely enthusiastic gardener. Samuel Dixon (fl. 1748-1769), dedicated his wonderful flower pieces of c. 1748 to the 6th Earl and his Countess. The chapter on Killruddery charts the evolution of the house and gardens, when in 1820 the 10th Earl commissioned Sir Richard Morrison and William Vitruvios Morrison to extend the original 17th- century house which evolved into the splendid Elizabethan Revival house we see today. Two decades later, the Scottish architect Daniel Robertson (d. 1840) was employed at Killruddery where he produced plans for stone balustrading and pedestals that today screen the lawns by the house. Robertson had fled Britain in disgrace in the 1830s, though on arrival in Ireland he enjoyed considerable success.

Robertson had also previously worked at Powerscourt, and not surprisingly Butler and Davies also cover this demesne in great detail. Powerscourt of course, was the seat of the Wingfield family and a wonderful three-quarter length portrait of Richard Wingfield, Ist Viscount Powerscourt (1697-1751) by the portrait painter Anthony Lee (d. 1767) is reproduced, with the famous Powerscourt waterfall and Deer Park in the background.

The same Viscount commissioned the German architect Richard Castle (1690-1751) to design his new Palladian mansion in 1731. Powerscourt’s romantic setting attracted visitors from the earliest days, long before the splendid Italian, English and Japanese Gardens were created by later generations of the Wingfield family. During his tour of Ireland (1776-78), the English traveller and author Arthur Young (1741-1820), for example, ound much to praise in Powerscourt’s mountainside setting:‘Kept on towards Powerscourt, which presently came into view from the edge of a declivity. You look full upon the house, which appears to be in the most beautiful situation in the world, on the side of a mountain, half-way between its bare top, and an irriguous vale at its foot. In front, and spreading among woods on either side, is a lawn whose surface is beautifully varied in gentle declivities, hanging to a winding river‚’.

Charles Grey, RHA (c. 1808-92), the landscape and portrait painter, was a friend of the Powerscourts and his watercolour, Powerscourt House, south front (c.1835) provides an important record of the grounds prior to the laying out of the formal gardens by Daniel Robertson over a three-year period from 1841. Robertson, perhaps falling back on the ways that had brought him disgrace in Britain, was said by Mervyn Wingfield, 7th Vicount Powerscourt (1836-1904), to have drawn his plans best ‘when his brains was excited by sherry‚’. He suffered from gout and as a result was driven about in a wheel-barrow with his bottle, and as long as this lasted he was willing to direct the workmen, but once finished he was incapable of any further tasks. Yet he was held in high regard by his employer.

Powerscourt is justifiably world-famous for its gardens, though for the 18th-century traveller and artist, the waterfall, the highest in Britain and Ireland, provided much inspiration. George Barret, senior (1732-1784), one of the most renowned Irish landscape artists of the 18th century, painted a number of scenes at the waterfall. His best, undoubtedly, is view of Powerscourt Waterfall (Fig 3). Barrett perfectly captures the foaming cataract as it hurls its way down a steep precipice, viewed by shepherds from the dark woods in the foreground.

The Wingfields were also once owners of the lovely Luggala Estate near Roundwood, though the romantic 18th- century landscape surrounding the pretty hunting lodge there was first created by the wealthy Huguenot banker David La Touche (1704-85). John Henry Campbell (1757-1828), the Dublin-based landscape painter, captured the dramatic setting of the elegant lodge, with its large Gothic windows, set deep beneath wooded cliffs as the powerful Cloghoge River cascades over rocks beneath a rustic bridge and forced its way down the spectacular glacial valley before finally meeting Lough Tay. Luggala is undoubtedly one of the most romantic glens in Wicklow and this chapter provides readers with a tantalizing glimpse of this private demesne.

He suffered from gout and as a result was driven about in a wheel-barrow with his bottle, as long as this lasted he was willing to direct the workmen, but once finished he was incapable of any further tasks

William Ashford (1746-1824) arrived in Ireland when he was just eighteen and became one of the country’s most respected landscape painters. One of the most charming scenes reproduced in this title is Mount Kennedy, painted in oil in 1785, showing the newly-built mansion surrounded by demesne parkland and woods, as the owners, an elegantly dressed couple on horseback dominate the foreground [detail seen on cover]. Ashford’s prospects of Irish country seats are full of charm and perfectly capture the scene of idyllic 18th-century elegance. His depiction of Mount Kennedy and Dunran, the home of Lt General Robert Cunningham (1726-1801) near Newtownmountkennedy, is perhaps one of his most romantic and utterly charming works.

Kilmacurragh, the seat of the Acton family is also generously treated. Well-executed crayon sketches (the work of various Acton family members) depict the house in 1740, in its original form (Fig), and again in the mid 19th century, following the addition of the two ‘famine wings‚’ in 1846. The gardens at Kilmacurragh became internationally famous in the late 19th century when the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew and Glasnevin supplied plants gathered by the great plant hunters from every corner of the globe. The French missionary P√®re Jean Marie Delavay’s (1838-1895) collections also reached Kilmacurragh from western China and in 1904 Rhododendron delavayi flowered for the first time in cultivation. Flowering material was duly dispatched to Kew in London where it was painted by the noted botanical artist Matilda Smith (1854-1926) to appear in Kew’s Curtis’s Botanical Magazine in 1907.

Eminent botanists like the Veitchian plant hunter Frederick Burbidge (1847-1905) left glowing accounts of the plant collection, then second only to the botanic gardens at Glasnevin and Lydia Shackleton (1828-1914), then employed by Sir Frederick Moore at Glasnevin as a botanical artist, painted several of Kilmacurragh’s new exotic plants in the late 19th and early 20th century. Artists continue to find inspiration at Kilmacurragh and Andrea Jameson’s recent depiction of the famous crocus lawn there closes the chapter on this particular garden.

While the gardens at Kilmacurragh has survived the ravages of the 20th century, not all Wicklow gardens have been as fortunate. Glenart Castle near Arklow still stands, though its elaborate gardens, elegant conservatories and box-edged parterres have long since disappeared. Lord Wicklow’s Shelton Abbey (Fig 4), where beech trees were planted for the first time in Ireland is still extant, though is today an open prison.

Wicklow has also been called the ‘Rebel County‚’ and many great demesnes were lost during the 1798 Rebellion and during the troubled years between 1916-1923. The demesnes of West Wicklow are less well-known by comparison to their easterly counterparts, though one that I was particularly happy to see featured is Saunder’s Grove near Baltinglass. In his Topographical Dictionary of Ireland (2 vols, 1837) Samuel Lewis (c. 1782-1865) described the early 18th century mansion as being built ‚’‚Ķ of hewn stone lined with brick, beautifully situated in a rich demesne adorned by the windings of the Slaney‚’. The original house at Saunder’s Grove was built in 1718 by Morley Saunders, MP, who had been prime serjeant-at-law to Queen Anne, and was surrounded by extensive Dutch-stye canals, formal cascades and splendid avenues. Alas, the house at Saunder’s Grove succumbed to the troubles of 1923 and, while the house was replaced, little now remains of its once great garden.

There is much that’s new in Wicklow through the Artist’s Eye and it stands as an excellent record of the county’s finest gardens and estates shaped over the past three centuries.

Seamus O’Brien manages the National Botanic Gardens, Kilmacurragh, Co. Wicklow.