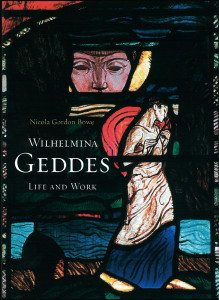

NICOLA GORDON BOWE

Four Courts Press, 2015

pp 508 fully illustrated in col h/b

€50.00 ISBN: 978-1-84682-532-3

Medb Ruane

When Thomas McGreevy spoke of Wilhelmina Geddes (1887-1955), he placed her with Jack Butler Yeats as the most talented young artist working in 1920s Ireland. A critic and mentor of Samuel Beckett, who became Director of the National Gallery of Ireland, McGreevy’s word was sound. Yet it has taken some ninety years for Geddes to receive the scholarly attention her work deserves, starting with Nicola Gordon Bowe’s appreciation of her war memorial windows in Irish Arts Review, Spring 2015, which previewed the author’s excellent new book on her life and work.

Gordon Bowe’s meticulous recovery of original material parallels her rewriting into history of this dazzlingly talented artist who was always an outsider – a stained glass artist in an age that privileged painting, a woman in a mainly man’s world, a Northerner in post-Treaty Dublin and an Irishwoman in mid 20th century London. Geddes did cover more ground than most of her contemporaries. Her professional footprint reaches from Ottawa to New Zealand, with fine examples of her work still remaining in Rathgar, Belfast and Ypres, among other locations. Critically, however, she became overshadowed and for Gordon Bowe, who spent thirty years on this research, the question is ‘why?‚’

Born in Leitrim, Geddes was the eldest of four children raised in Belfast by their unhappy parents William and Eliza Jane. Father was a chronic alcoholic who became addicted to laudanum, Mother a genteel lady whose anxiety attacks were so profound that her daughter reversed the usual order of things and became her protector. This created a lifelong push-pull for Geddes who eventually died within weeks of her mother’s death.

Daisy, as Wilhelmina was called, was what we would now call a gifted child, a voracious reader and writer who studied Homer and began to learn Greek. William’s rages grew through her childhood, so that she was afraid to sleep and then to dream. At sixteen she wrote that ‘there was no chance even of getting married having a father like that‚’ and by twenty of the ‘deadening nightmare of being alive.‚’

Geddes became an artist rather than a writer because it seemed to offer her a better living. She won so many prizes in Belfast’s Art College that its competition rules were changed. Curiously, her drawings of Cinderella – the outsider in the family – were what caught the attention of Sarah Purser, who invited her to join her glass workshop An T√∫r Gloine. Yet she was restless, wanting to go to London while being unable to leave her mother, falling ill with severe depression and the impossibility of it all. Her mental state was so fragile that she referred herself for therapy with a local doctor who, like her, had read Freud. By 1925, aged thirty-eight, her illness delivered an unexpected wish when she had herself admitted as a voluntary patient to London’s Maudsley Clinic, where after a six months‚’ stay, she started therapy with the eminent Freudian Dr Edward Glover, and began a lifelong engagement with psychoanalysis and London, where she remained.

Gordon Bowe’s inclusion of her case notes from the Maudsley is as fascinating clinically as is the tracking of Geddes‚’ editorial work on Glover’s considerable, important publications. Other Irish artists such as Elizabeth Bowen, Samuel Beckett, and, via his daughter Lucia, James Joyce also engaged with the discipline but what marks Geddes out is the link between her art and her analytic engagement, the way she put her suffering to work. Initially diagnosed with Obsessional Compulsive Disorder, she would probably be diagnosed differently now, because there was no viable analytic theory of trauma and psychoses then. Some indications suggest childhood abuse – her father’s ‘irresponsibility when drunk‚’ is linked to her phantasies about pregnancy and her ‘ceremonials before sleep‚’ may reflect fears of darkness, sex and death. Nor were there anti-psychotic medications, which might have eased her periodic crises. Her cold studio, lack of money and lack of self-care are at odds with the pristine standards she demanded for her work.

Glover gave her writing and editing work that created a small income stream. This places Geddes at the centre of key psychoanalytic debates and concepts. In a way, the psychoanalysis licensed her to explore the very idea of fracture within her stained glass, creating beauty and formal unity from brittle, fragile stuff.

Medb Ruane is a writer and practising Lacanian psychoanalyst based in Dublin.