The recent discovery in Finland of three new Kollwitz works missing since the end of World War II will have pleased those who enjoyed the recent exhibition of her work entitled ‘Life, Death and War’ at the National Gallery of Ireland. Critical attitudes to Kollwitz have become quite ambivalent of late. Her work has always been political but recently in her native Germany she has been referred to as a conservative artist for reasons that remain unfathomable to this writer. Whilst remaining a doyenne of the contemporary left, they constantly struggle to redefine her as they evaluate her focus on the specifics rather than the generalities of exploitation. Feminists have continued to be sympathetic and ‘Semper Fi’, given her stance on and experience of misogyny and abuse, but from the 1970s onwards Germans have developed an attitude towards her which is complex and uncomfortable.

Betroffenheitkitsch is not a word that trips lightly off the tongue but it describes a dismissive attitude which identifies and rejects empathetic kitsch and some German critics fear that she is guilty of trespassing into that zone. People generally like their political art to come ready formed complete with bells, whistles and drums, promising the complete and uncomplicated Agit-prop experience. Kollwitz is sometimes compared with Weimar artists like Otto Dix, George Grosz, Max Beckmann and Hannah Höch and found to be deficient. She appears to have transgressed some critical orthodoxies which revered detached post-war artistic identity clichés. This is a misreading of an artist whose great themes encompassed motherhood, death, loss, war, hunger and survival.

from the 1970s onwards Germans have developed an attitude towards her which is complex and uncomfortable

Deficient no, different yes. Kollwitz treats her subjects with subtlety and restraint. Her early work was deployed in the service of leftist politics and although propagandist in the main, her poster imagery contained the kernel of the later potent expressions of sympathetic human engagement which characterised her career. In Germany it was suggested that a form of ‘Kollwitz fatigue‘ had set in by the 1970s. Certainly Berlin and Dresden are very Kollwitz–aware and her subject matter still remains deeply challenging for some German sensibilities. However the strength of her character, her moral and creative force is reflected in the treatment of her great themes which she never sentimentalised, romanticised, or consciously heroicised. In 1993 Helmut Kohl, the then Chancellor gave recognition to this when he selected a version of Kollwitz’s Mother and her dead son sculpture to be placed in the Nueu Wache memorial building on the Unter den Linden in Berlin.

So much of political art is understandably aggressive and confrontational. This is not the case with Kollwitz. Her anger has transmuted into poignancy and sadness and her works continue to reflect a sublime expression of deeply-held humanistic values.

Gerry Walker is an art critic.

Image: Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945) Krieg, 6: Die Mütter, 1921 (War, 6: The Mothers) Woodcut on paper Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, Graphische Sammlung

Photography’s power to influence our perception of the natural world and its fragility has been gaining impact with the rise in awareness of climate change.

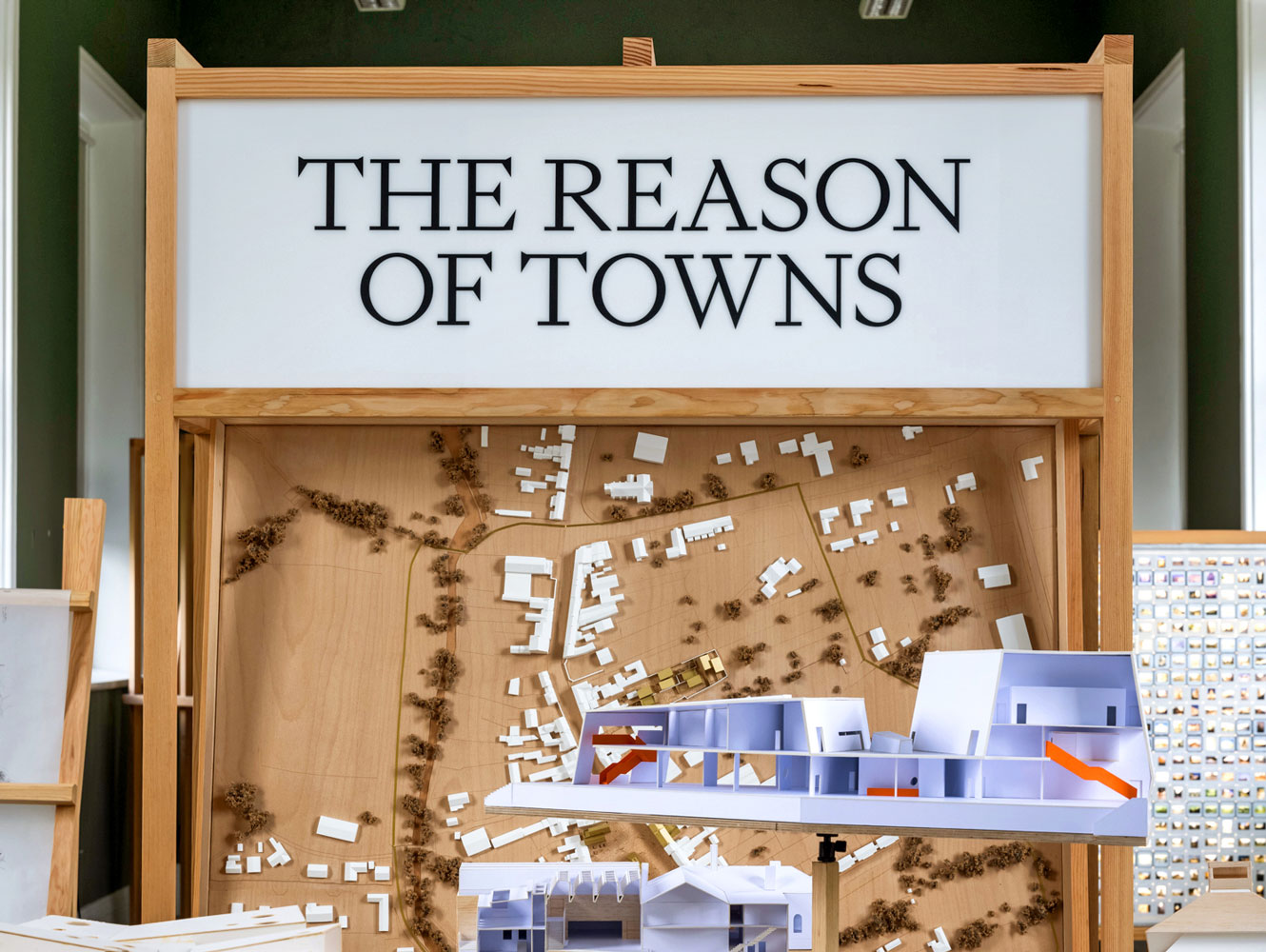

Touring Ireland over the past six months, ‘The Reason of Towns’ celebrates the design qualities of Irish towns and aims to motivate people to choose them as a place to live.

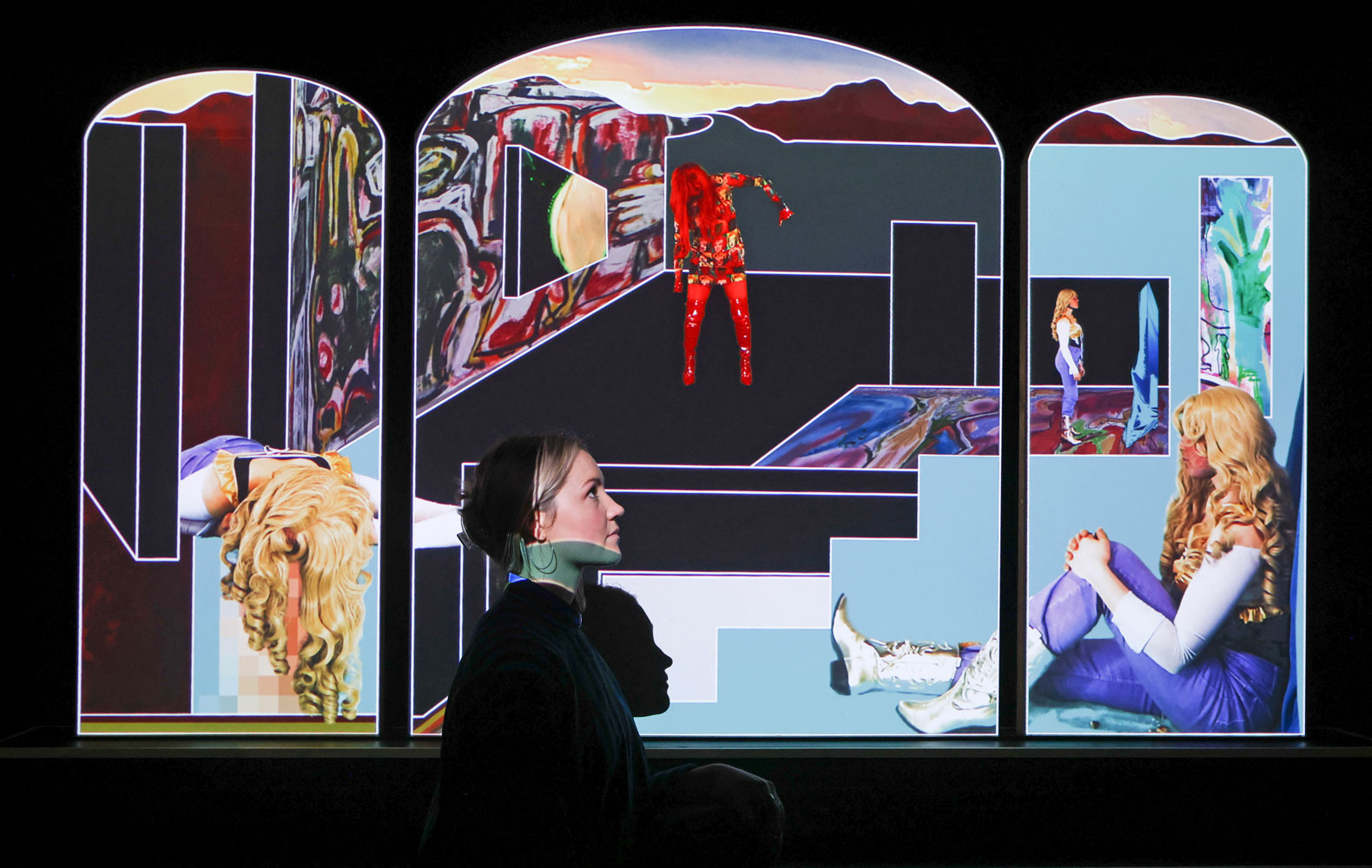

The winner of the 2024 RDS Taylor Art Award, given to the most promising emerging visual artist of the year in Ireland and worth €10,000, is Sorcha Browning.